Years ago, an actor performing in an early play of mine told me that I never seemed to write likeable characters. Being an insecure early-career playwright, I asked if that was a bad thing. “Not really,” he said, “I think it’s just the way you write.” Initially that stuck with me. Maybe it was a shortcoming in my work. Maybe I had to try harder to write characters my audience could like and connect to. Maybe that was the key to cracking the code of whatever success was. But I didn’t dwell on it. My writing changed and improved and developed, but I never really arrived at a place where I knew how to or even cared much about writing ‘likeable’ characters. Of all the questions I’ve asked beta readers about my work – did this surprise you, did you see this coming, were you engaged – I don’t think I’ve ever asked whether they liked a certain character. The question I’d be more inclined to go with, and the question I’m more interested in the answer to, is ‘what did you think of that character?’ It probably seems like a small distinction, but it’s important. We were taught a lot about likeability at film school but I always kind of tuned it out. I think I knew why back then even if I didn’t yet have the language to explain it. Likeability was just never a factor in any of the characters I found most compelling. Is Don Draper likeable? Is Walter White? Hannibal Lecter? Lisbeth Salander? You might respond to a couple of those names with a resounding yes, to which my answer is, cool! But I’d also argue that for many people, likeability is the last word they’d associate with those characters. They divide opinion and to me, that is why they are great characters. We all know people who are roundly likeable, but it’s very, very rare that anyone is liked by everyone. People aren’t Marvel heroes – funny and charming and self-deprecating enough to feel ‘real’, but ultimately always heroic. People are a lot more complicated than that and in the cases of the people you care about, really care about, it’s not because of their likeability. People can be likeable but still cowardly, shallow, ignorant, whatever. Likewise, many people of great integrity and honesty would be considered ‘unlikeable’ by any Hollywood focus group. I think people have become less comfortable with ambiguity. I’m sure there are plenty of social factors for this, but it does seem like we’ve seen a shift away from a willingness to sit in unanswerable grey areas. In a weird way I think that Game of Thrones provides a unique case study of this. In the early seasons, ambiguity was what made it so compelling. The traditionally heroic characters didn’t last. Seemingly irredeemable characters looked very different once you came to understand them. Then certain characters became favourites and became increasingly one note as the show gradually lost ambiguity to the point where the ending, which tried (not very well) to restore some moral uncertainty was roundly rejected due to seeming so at odds with what had come before. I still argue that all the seeds for Daenarys’ turn are in those early years, but the later seasons dropped the ball so terribly that people forgot this was supposed to be a show without heroes or villains and fell into comfortable binaries. One of the most fascinating recent case studies of widespread discomfort with ambiguity was the character of Cliff Booth in One Upon a Time in Hollywood. Cliff is a washed up stuntman played by Brad Pitt at his most easily charming. He also, potentially, killed his wife in cold blood. The film never directly confirms this (although the novel version does) and it is, at least on screen, treated as a minor aspect of his character. When the film came out there was a lot of peal-clutching about this. Review after review seemed to cry “how are we supposed to like him?” and in the process missed the point that at no stage in the film does Tarantino suggest you are supposed to like him. The reason Cliff Booth is a great character is that his toughness, bravery and charm go hand in hand with a blithe disregard for human life. The book, for my money, does a better job of making clear how intentional this is; Cliff in the book is far more troubling than he is on the screen, partly because there’s no Brad Pitt charisma to mask his less savoury traits. But that doesn’t mean Tarantino is positioning him as a villain or someone ‘unlikeable’. I don’t think he’s being positioned as anything other than a character in a story. Like him? Don’t like him? That’s entirely up to you. And it’s shocking to me that commentators somehow struggled with this – when has Quentin Tarantino ever written a character you’re supposed to just like without complications? The Bride in Kill Bill murders a mother in front of her child. The guys in Reservoir Dogs are thugs. The Basterds in Inglourious Basterds are bloodthirsty brutes who shoot a bunch of defenceless dogs to coerce a vet to help them (watch the background of the vet scene, or else read the screenplay if you don’t believe me). And of course they are. The kinds of people who can commit the acts they do are not, by any binary understanding of the concept, good people. Which in a roundabout way brings me to Maggie. Now, to get this out of the way – clearly I like Maggie. I wouldn’t have written several books and short stories about her if I didn’t. But there’s no part of me that thinks you as the reader have to like her. Skim reviews of The Hunted and The Inheritance for a taste of how she divides people – readers seem to like her more in the second book, but more than a few have come back saying she’s a ‘psychopath’. Is she? Isn’t she? That’s up to you. She tries to do good and help people where she can. She feels remorse for her mistakes. She’s haunted by guilt and a horrific childhood. She’s also a cold-blooded killer who couldn’t care less about ending the life of somebody who tries to hurt her. Maybe she even enjoys it. She has made deeply selfish choices that got innocent people killed. She feels those choices, hates herself for them, but that didn’t stop her making them. Just because I wrote her and like her doesn’t mean I think there’s any right or wrong way to feel about her. Likewise Jack Carlin in The Consequence, a violent, ruthless man with a warped code of honour and a wicked sense of humour. Or Nelson in The True Colour of a Little White Lie, a bumbling, awkward, well-meaning kid who still selfishly lies to two girls to save himself from having to make a choice. None of this is to suggest that I like every protagonist I’ve ever written. I usually have some level of empathy for them, because, well, I have to, but there are plenty who I didn’t particularly care about. But the one thing they all had in common is that, on one level or another, something about them interested me. That might just have been down to a choice they had to make, as in a lot of my plays. Or it might have gone further, in the case of Maggie or Boone Shepard, where I kept writing about them because I knew there were depths I wanted to fully explore. But the one thing I’ve never cared about was whether they came across as likeable. In a weird way, I think that fixating on likeability, for a writer, can be dangerous. And, often, cheap. Employing screenwriting manual mandated techniques to make the audience like a character early robs them of the chance to come to that conclusion themselves. For me there is nothing in a story quite as exhilarating as slowly realising that I like a character or that I was wrong about my initial assumptions of them. One of the best examples is Steve Harrington in Stranger Things – the reason people are so connected to that character is that we weren’t positioned to like him at the start and slowly grew to as we got to know him. Almost like how we make friends in real life. Contrast this with a clip I saw from a recent episode of Doctor Who that introduces a new companion by having him say ‘what’s the point of being alive if you don’t make other people happy?’ Which even a child could tell is the writer smashing you over the head with the fact that you’re supposed to like this guy. It's infantilising and annoying. There are audiences who will quickly check out if they don’t have a reason to like a character. But I would also argue that far more important than liking a character is empathising with them. Which many people assume is the same thing but it’s absolutely not. Somebody once described books as ‘empathy machines’ and for good reason. Stories allow us the chance to explore the minds of people who are nothing like us. Bad people, complicated people, different people. But all people. Stories can make us view the world differently simply by presenting the perspective of somebody who doesn’t think the same way as you, in the process forcing you to consider the divide and therefore giving you something to think about. The moment we start insisting that the most important thing is that our characters are likeable, or ‘good role models’ or whatever, we lose what makes stories special.

0 Comments

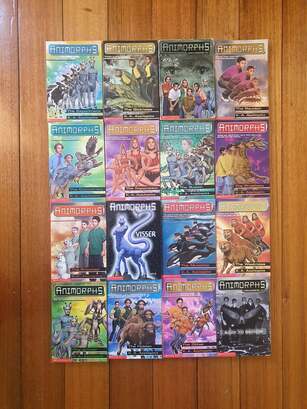

Including the ‘companion’ books that flesh out the backstory and lore in important ways, there are sixty-two Animorphs books in total. Granted, these are slim volumes that you can smash out in a couple of hours, but even so, taking on this series is a commitment. Especially given that they’ve been largely out of print for twenty years - while the eBooks are available for free online and there’s an ongoing graphic novel adaptation, tracking down the entire series can be a difficult and expensive proposition. But the thing about having that many books is that not all of them are necessary or even, frankly, good. The second half of the series is packed with filler novels that either stall or actively damage development, and so the best way to read this series (which remains very, very worth doing) is to be a little judicious in which books you read and which ones you ignore. You can read less than half the Animorphs books and still have a great time. Possibly an even better one. So which books do you absolutely need to read, which ones can you skip, and which ones fall somewhere in the middle? Below is my assessment of every Animorphs book in release order. Ratings Key: Essential: Advances the plot, themes or characters in crucial ways. Recommended: The series works fine without it, but there’s worthwhile stuff here. Skippable: You have little or nothing to be gained from reading this book. 1. The Invasion – Essential Jake, Rachel, Cassie, Tobias and Marco learn of a secret invasion and are given the power to morph by a dying alien. Sets up the world and characters with fast paced efficiency and a tight, propulsive structure. A great introduction which hides in plain sight all the big themes and ideas that will come to dominate the series. 2. The Visitor – Recommended Rachel investigates her friend’s Controller father. Some good character development for Rachel and further establishment of the stakes, but doesn’t do anything that later books don’t do better. Plus, in these early books the climax is almost always the same and will start to grate after a while. 3. The Encounter – Essential Tobias struggles with being trapped in the body of a hawk. Doesn’t really progress the plot, but in terms of both theme and character the series is poorer without it. The deeper, more ambivalent ideas about identity that Animorphs got very good at exploring really start to take hold here and even by the end of the series this remains one of the strongest examples of that. 4. The Message – Essential The Animorphs rescue trapped Andalite Ax from the ocean. Not nearly the best book in the series, and a little repetitive in terms of plot beats, but crucial plot-wise – Ax is a great character and you can’t miss his introduction. 5. The Predator – Essential The Animorphs go to space and learn the identity of Visser One. Great character and world building plus a game changing twist essential to the series going forward. In hindsight one of the most pivotal books in the series and the beginning of one of its most wrenching, nail-biting arcs. 6. The Capture – Essential Jake becomes a controller. Do not read Animorphs and not read this book. Fantastic world building, effective exploration of stakes and a great central dilemma. Like The Encounter it doesn’t exactly advance the overall plot but lends so much depth you really can’t miss it – along with some creepy foreshadowing for what is to come. One of the earliest hints that the story Animorphs is telling is much, much bigger that what you might initially assume. 7. The Stranger – Essential A cosmic being called The Ellimist gives the Animorphs the choice to continue fighting a battle they’ll lose or to escape with their loved ones to a safe planet and abandon Earth to its fate. Another major player introduced, plus a great dilemma, some nice worldbuilding and a big series turning point. The resolution is both surprising and satisfying while economically setting up another major running thread that will be properly examined way down the line. 7.5. Megamorphs #1: The Andalite’s Gift – Recommended The Animorphs are hunted by a creature who can sense morphing. A fun blast of blockbuster action after a succession of heavy books and a great wrap to the series’ first act. Like all of the Megamorphs books you don’t need to read it exactly, but unlike the other Megamorphs books it’s just so much fun and really reads as a chance to go on a rollicking, chase adventure with these characters. No heaviness here but no irritating silliness either. If Animorphs was ever made into a sanded down Hollywood movie that avoided all the darkness, this would be the place to start. 8. The Alien – Essential Ax attempts to make contact with his home world. Adds shades to both a central character and major villain, while fleshing out the series backstory in clever, crucial ways. Just a great read packed with fascinating detail, humour and heart. In retrospect the early run of the series is across the board its most consistent and this is a highlight. 9. The Secret – Skippable The Animorphs try to stop the Yeerks from using a logging operation as a front to smoke them out. Doesn’t really progress the plot and has a goofy as hell ending, but plays with some interesting ethical dilemmas especially as pertains to Cassie’s empathetic environmentalism and Tobias’ new nature as a predator who has to kill to survive. But really, that’s about it and on its own not enough to recommend it. 10. The Android – Essential The Animorphs discover they have allies in a peaceful race of Androids called the Chee. More major new players and worldbuilding, plus some serious darkness towards the end. That said, this also marks the first significant time the Animorphs make a choice that will have you yelling at the book wondering what the hell they were thinking, especially come later books. 11. The Forgotten – Skippable The Animorphs get trapped in the Amazon twelve hours in the past. Fitting title for a story that literally retcons itself at the end. Adds a bit of depth to Jake, but not enough to justify its own existence. It’s a struggle to remember anything specific from this book. 12. The Reaction – Skippable Rachel has an allergic reaction to a morph and loses control. Kind of fun, but silly and weightless. Probably don’t bother. 13. The Change – Essential The Ellimist offers Tobias his morphing powers back in exchange for helping to rescue two escaped Hork Bajir. A game changer in more ways than one. Unmissable. I don’t think there’s a single Tobias book that I would recommend skipping, but this is the biggest of all of them in terms of the new elements it introduces. 13.5. The Andalite Chronicles – Essential The full story of how Elfangor ended up on earth. Integral backstory, gut punch tragedy and fantastic sci-fi pulpiness. Not quite Animorphs at its absolute best (that would be the next Chronicles) but a great read that enriches the entire series and provides crucial context for what is to come, while also turning Elfangor from a benevolent saviour into someone a bit more complicated with key parallels to the Animorphs themselves. 14. The Unknown – Skippable The Animorphs attempt to infiltrate a government base and learn what alien technology they’re hiding. Turns out, a toilet joke and far from the first in this book. Decide for yourself if that’s for you or not. 15. The Escape – Recommended The Yeerks attempt to turn hammerhead sharks into Controllers to invade an underwater planet. Builds on previously established plot points and in the moment progresses things only slightly, but is important for forthcoming events. 16. The Warning – Recommended The Animorphs learn of a Yeerk serial killer. Not integral to the overall plot, but a great encapsulation of how far our central characters have sunk morally with a deeply troubling final choice and a chilling ending that refuses to give comfortable answers. One of the first hints that maybe the Animorphs are not really heroes. 17. The Underground – Skippable Oatmeal turns out to be a Yeerk drug and the Animorphs decide what to do about it. An interesting enough central dilemma, if completely ridiculous, but it’s not explored in a way that makes the most of it. 18. The Decision – Recommended The Animorphs end up in the midst of the battle for an alien planet. I highly recommend this one for its world building and for Ax, but you won’t lose a huge amount without it. It’s super enjoyable and if like me you love the lore of this world then this book has heaps to offer, but I think it only comes up again like, once, and vaguely at that. 18.5. Megamorphs #2: In the Time of Dinosaurs – Recommended An attempt to rescue a nuclear sub blows the Animorphs back to the Cretaceous Period. Inherently silly and inessential, but with a third act moral dilemma that’s genuinely knotty and a hugely upsetting finale. It’s scuppered a little bit by only rarely coming up again and having no tangible impact on the characters going forward, but despite fan dislike it’s a hugely enjoyable read and I defy you to get through the final pages still feeling okay about, well, anything. 19. The Departure – Essential Cassie is stranded in a forest with an injured Yeerk controller who knows her secret. Ooh boy, is this a great read. Effectively a two-hander morality play that finally gives us a sympathetic Yeerk perspective and complicates everything the Animorphs considered to be straightforward. Let down by a way too convenient ending, but an absolute highlight all the same, and one that turns out to be integral to the series’ resolution. 20. The Discovery – Essential When a student at their school discovers the Morphing Cube and becomes a target of the Yeerks, The Animorphs must decide whether to recruit him or leave him to his fate. The start of a three-book arc, this is very much a first act but given what it sets up you can’t not. 21. The Threat – Essential The Animorphs acclimate to their new member. The second act in a story, it has an absolutely horrifying cliff-hanger ending – as a kid I never read the third part and it haunted me for years. The last third of the book is pulse-pounding stuff that turns our understandings of the characters’ roles within the team on its head and brings to light burgeoning ideas that have so far hidden in plain sight. 22. The Solution – Essential The Animorphs try to deal with a uniquely dangerous enemy – one of their own. Holy crap, what a resolution. This book is packed full of twists and genuine surprises. And the ending is one of the most unsettling moments in a series full of unsettling moments. This trilogy is Animorphs at its bleak, uncompromising, fiercely intelligent best. Some of these books are slogs, some are easy if not especially propulsive reads and some are absolute page turners. This exemplifies the last type and then some. 22.5. The Hork Bajir Chronicles – Essential The full backstory of how the Yeerks took over the Hork Bajir and the futile guerrilla efforts to stop them. Oh man. Oh man, oh man, oh man. When people try to laugh off Animorphs, this book is the only rebuttal necessary. A devastating sci-fi parable about the costs and complexities of war that also serves as a parallel for the main books. It shows where the war started and where, in the worst case scenario, it could go. Deserves to be a classic even without the rest of the series. Brilliant. 23. The Pretender – Essential Tobias discovers that a cousin he’s never met wants to take him in, leading to him learning the truth about his parentage. Not only is it a game changer, but it has some of the best writing of the series with some powerful reflections on humanity, morality and identity. The plot surrounding the big revelation and Tobias’ development is kind of flimsy, but like most Tobias books that development alone is worth it and then some. 24. The Suspicion – Skippable The Animorphs deal with a race of miniature aliens bent on world domination. Funny at times but very silly and does absolutely nothing to progress the plot. Probably necessary after a few gut punches in a row, but still, not exactly top-tier stuff. 25. The Extreme – Skippable The Animorphs head to the North Pole to destroy a Yeerk base. This one is disposable, but it’s also pretty fun with some edges of darkness peppered throughout. Quick to breeze through, won’t leave a lasting impression, but won’t emotionally devastate you either. If you want pure entertainment from your Animorphs, you can do a lot worse. 26. The Attack – Essential The Ellimist enlists the Animorphs as his champions to save an alien race from his rival. This is one of the most satisfying books in the whole series, hands down. Not only does it show the full scope of what’s at stake, not only does it offer real glimmers of hope, but it’s also just a cracking read with brilliant twists, great world building and punch-the-air moments. All in something like 25,000 words. Brilliant. 27. The Exposed – Skippable When their android allies the Chee begin malfunctioning, the Animorphs have to find a way to reach their submerged ship and fix them. Introduces an interesting new player and furthers Rachel’s internal struggle with her own nature (along with her relationship with Tobias), but as a story it’s not a standout and ultimately is a bit wheel spinning. 28. The Experiment – Skippable The Animorphs investigate a Yeerk experiment at a slaughterhouse. Maybe one of the most pointless books in the whole series. Some funny Ax material, but even the feints at moral ambiguity feel half-hearted. Plus the ghostwriting is super obvious. Profoundly unnecessary. 29. The Sickness – Essential When Ax comes down with an alien illness that quickly spreads to the other Animorphs, Cassie is forced to work alone to rescue an unlikely ally. A sequel of sorts to The Decision, this develops what that book set up, establishes the Yeerk Peace Movement and goes to some moving places. A great read with some decent plot progression. 29.5. Megamorphs #3: Elfangor’s Secret – Recommended When Visser Four finds the time Matrix and attempts to change human history the Animorphs are enlisted to stop him. This book is a mixed bag. One of my favourites as a kid, it’s a brutal exploration of humanity’s affinity for war with a lot of shocking moments and big ideas, but it’s let down by a heavy ending that, for once, rings hollow due to the Animorphs having several obvious better choices. 90% of a great read, but doesn’t quite hit ‘essential’ status. 30. The Reunion – Essential Marco discovers that his Yeerk controller mother is on the run from the Yeerks. A great book for Marco that explores his growing ruthlessness and how it comes into conflict with his mother’s plight. Let down a little by slightly loose plotting and a couple of leaps in logic, but includes some fairly major plot progression and sets up big things to come. 31. The Conspiracy – Skippable Jake attempts to stop his Yeerk controller brother from killing their father. Nothing in this book is exactly necessary, but it’s worth the read for its gripping cat-and-mouse games, tough moral dilemmas, and well-considered reflections on what war does to people. 32. The Separation – Skippable After being cut in half in starfish morph, Rachel regenerates into two versions of herself with different personalities. Fans hate this book but I found it kind of fun. I laughed a bunch and it was nice to have Applegate back at the wheel after a few ghost-written books. It’s also a decent character study of Rachel. But in terms of necessity to the series, you can easily skip it. 33. The Illusion – Essential As part of a ploy to find and destroy a Yeerk weapon, Tobias allows himself to be captured. Oh man this book hits hard. It’s dark as all hell and a seriously troubling read – it’s essentially Tobias being tortured, a lot – but there are moments of power and beauty here too. If you’re being incredibly ruthless with your read then I can’t say that it’s entirely necessary, but for Tobias’ arc and just straight up great writing, I’m going to give it the ‘essential’ rating. 34. The Prophecy – Recommended In order to help the Hork Bajir take back their home world, Cassie has to let herself be inhabited by the essence of a long-dead Andalite hero with crucial information. Basically a sequel to The Hork Bajir Chronicles, this book continues that one’s tradition of breaking your heart and also being an exceptional read. This is emotional, thought provoking, packed with moral ambiguity. An absolute winner even if its events never come up again. 35. The Proposal – Skippable Marco struggles with his father’s new relationship. A week or so after finishing this I could barely remember what happened in it. There’s some very minor plot progression in Marco’s father remarrying, a cliff-hanger at the end that sets up Visser, and some great jokes at the band Hanson’s expense, but otherwise this is totally disposable. 35.5. Visser – Essential Visser One is put on trial and the origins of the Yeerk invasion are explored. For the first half, this is A-grade Animorphs with excellent worldbuilding and some brilliant twists, turns and sci-fi ideas, but it comes apart a bit as it goes, becoming borderline confusing and gradually feeling less and less vital. Still, it features the first real ‘reunion’ between Marco and his mother and some long awaited answers to big questions which nicely establish the stakes going forward. 36. The Mutation – Skippable A mission to destroy a new Yeerk ship leads the Animorphs to a nightmare Atlantis. Some creepy imagery and cool ideas, but this late in the game books like this just aren’t needed. It doesn’t do anything other books haven’t done better and, while entertaining, is ultimately forgettable. 37. The Weakness – Skippable Jake leaves town and Rachel leads the group on a series of reckless attacks. Obvious ghost-writing and weird characterisation do Rachel a massive disservice here, resulting in a book that’s neither enjoyable nor important. Probably the worst in the series. Just don’t. 38. The Arrival - Recommended The arrival of an Andalite hit squad divides the Animorphs. Such a great book – tense, unpredictable, with a cracking central mystery and a fantastic encapsulation of how far Ax has come and how low the Andalites have sunk. It doesn’t exactly progress the overall plot, but it’s so damn good that you’d be remiss to skip over it; one of those books that captures everything awesome about Animorphs, and a great palate cleanser after the atrocious previous one. 39. The Hidden – Recommended Cassie accidently gives morphing powers to a buffalo. This book has a Rick and Morty-esque way of taking a silly sci-fi idea and pushing it to its most nightmarish, horrible extreme. There are plot holes and logic leaps, which is hardly unique at this point in Animorphs’ run, but it manages to make you invest in this whole buffalo situation and the resolution is heartbreaking, if a bit too convenient. Plus the whole book is essentially a nonstop chase that is pretty top-to-bottom stressful. 40. The Other – Skippable The Animorphs discover more Andalites are hiding out on earth. Uncharacteristically for an Andalite heavy book, not a lot of any note happens here in terms of progression, worldbuilding, or interesting ideas. It’s sweet natured and a good Marco book, but apart from revealing that Ax (and the whole Andalite culture) is deeply ableist, there just isn’t enough here to make it feel that vital this late in the game. 40.5. Megamorphs #4: Back to Before – Recommended A war weary Jake makes a deal to change the past and stop the Animorphs ever getting their powers – or learning about the war. Despite being predicated on a somewhat out-of-character judgement lapse for Jake, this is a great ‘what if’ story that, due to its nature as a parallel timeline, becomes quite gripping and unpredictable while shedding new light on the characters. It’s not crucial to the plot, but it’s so damn enjoyable and shows how far everyone has come while highlighting that the seeds of their individual journeys have been in place from the start. It also implicitly answers several questions that, this many books in, readers are likely to start asking – such as why the Animorphs don’t use Ax to go public and reveal the invasion to the world. 41. The Familiar – Recommended After a particularly rough mission, Jake wakes up in a future where the Yeerks have won. This book is… weird. Especially coming immediately after one with a very similar plot and point. But they’re differentiated by the fact that this is effectively what would happen if David Lynch wrote an Animorphs book. The potential future is deliberately inconsistent and punctuated with bursts of bizarre dreamlike imagery; children sitting in an underground tree singing, the ghosts of everyone Jake killed coming for him, a devilish hybrid of Tobias, Elfangor and Ax. It ends with the hint of another powerful player out in the universe, but is never followed up on. It is completely unnecessary to the overall story, but it’s more memorable than plenty of books that are, even if it doesn’t entirely work. 42. The Journey – Skippable The Helmacrons invade Marco’s body, forcing the Animorphs to shrink and stop them. Okay so weirdly I enjoyed this way more than the previous Helmacrons book. I laughed out loud at several points and no matter how goofy the plot is, there’s fun to be had here. But it’s another late-stage book that doesn’t even pretend to advance the plot or characters, so I can’t exactly recommend it. 43. The Test – Recommended Tobias struggles with the aftermath of his torture when the Animorphs make a deal with the Yeerk responsible. Like all Tobias books, this is thought provoking, moving and a shining example of why Animorphs retains such a passionate adult fan base. It’s effectively a direct sequel to The Illusion and is predominantly concerned with Tobias coming to terms with not only the events of that book, but also the fact that he may have deliberately chosen to get stuck as a hawk. Important for his character and powerful in how it gently articulates that sometimes we never find a real answer to the things that torment us, but it doesn’t move much forward. 44. The Unexpected – Skippable Cassie contrives her way to a solo adventure in Australia. So look, it’s not great. But it’s not terrible either. This is one of those books that knows what it is and owns it; if you’re coming to Animorphs purely for the silly adventure stuff, then it’s fine. But let’s be real; nobody in the 2020s is coming to this series for the silly adventure stuff. I was perfectly diverted but knowing big plot is right around the corner didn’t do a heap to endear this book to me. 45. The Revelation – Essential When Marco’s father becomes a Yeerk target, the Animorphs are forced to reveal the truth – and everything changes. Man, after so many books of not very much happening, to have one with this many game changers packed in is nothing short of exhilarating. So many major plot threads come to a head here. The status quo is blown to pieces by the end and you’re left with the sense that the series’ final act has well and truly begun. On top of all that it still manages to pack in humour, heartbreak, a gut-wrenching moral dilemma and a punch-the-air moment of cathartic satisfaction. At this point Animorphs has been treading water for a while. Not anymore. Maybe the most important book since the very first. 46. The Deception – Recommended The Animorphs attempt to stop the Yeerks from engineering a third world war. What happens in this book isn’t entirely essential to the plot going forward, but it does represent a massive escalation of the stakes and conflict and really creates the sense that a Rubicon has been crossed and there is no going back. Plus it’s a great book for Ax in terms of examining his loyalties and unique position as an alien among humans. 47. The Resistance – Skippable The Yeerks discover the location of the free Hork Bajir, leading to a battle to protect their valley. Look, technically this book advances the plot, but it also pretty much sucks. Alternating chapters set in the Civil War are supposed to parallel the modern situation but are just annoying and even the present-day stuff is undercut by a lot of dumb decisions made by seemingly smart characters. In the end even if it does slightly move the pieces, nothing happens in this book that isn’t efficiently recapped later so you can easily skip it. 47.7. The Ellimist Chronicles – Recommended The Ellimist details his backstory to a dying Animorph. This is Animorphs at its most sci-fi, so your mileage may vary on how enjoyable you find it. It’s an engaging, clever and powerful read that gives a genuinely satisfying backstory to a character who might have been better off left a mystery, but reading it in release order is kind of frustrating as it feels like it kills the momentum and unlike the other Chronicles books there isn’t much in it that has any bearing on the mainline series. But it’s still a good book and enriches the mythology in surprising and memorable ways. 48. The Return – Essential David returns and attempts to take revenge against Rachel – with help. Okay so look, this book is a bit of a struggle at first. The plotting is wild and the use of dreams within dreams within dreams more annoying than anything. But it really examines Rachel’s role within the group and the internal struggle that has always characterised her. And the ending, which would seem like an unnecessary coda to the David Trilogy if it wasn’t so goddamn powerful, is one of the most haunting moments in all of Animorphs. 49. The Diversion – Essential When the Yeerks finally figure out their enemies are human, the Animorphs must race to evacuate their families. Everything just got very, very real. The game changes and then some as one by one the team try to rescue their loved ones – in some cases successfully, in others, not so much. This book is suffused with a sense of apocalyptic finality, a last desperate attempt to do some good before all hell is unleashed. And at the centre of it all is Tobias’ reunion with his long-lost mother, a returning character from The Andalite Chronicles. The first quarter of this book is your basic Animorphs. After that it’s a breathless, heart racing, moving, edge of your seat race that changes everything forever. 50. The Ultimate – Essential As their situation grows more desperate, the Animorphs are forced to begin recruiting. At this point in the series the game changers are coming thick and fast, and with them an overall shift in tone. There’s a consistent darkness and maturity running through these final books, a sense of discomfort at seeing these characters and their relationships begin to crack under the weight of what they’re dealing with, in some cases becoming almost unrecognisable. This book is packed with surprising turns and moral dilemmas, and ends on a seriously controversial choice by one of the characters – an important one, but one that might just have you throwing the book against the wall. 51. The Absolute – Essential When the Yeerks begin a plan to take over the National Guard, the Animorphs finally decide to alert the authorities to what is going on. Compared to the surrounding books this feels almost light, but it continues the sense of impending finality that’s been growing over the last few books. There’s a lot of fun to be had, laugh out loud lines, great action and charming character moments and considering how heavy everything’s getting, the almost-respite is quite welcome. Even if, by the last moments of this book, it’s clear that any chances for fun are now gone. 52. The Sacrifice – Essential The Animorphs must decide whether to take a chance to blow up the Yeerk pool – killing thousands of innocents in the process. And so we careen towards the series’ climax with another massive game changer rife with terrible choices and impossible-to-comprehend consequences. There’s some repetition here in terms of Ax’s character development, but definitive resolution as well as a grim table setter for what is about to come. 53. The Answer – Essential In the midst of open war Jake sets his final plan in motion. Oh boy. The climax of the series is an absolute barnstormer. Dark, emotional, wrenching and saturated with a growing sense of dread as you begin to understand what victory here will cost in terms of our heroes’ lives and souls. In these final books Animorphs feels different – there’s not much humour and any pretence of being what would traditionally be considered ‘kid friendly’ is out the window. The choices made here will stick with you no matter your age. 54. The Beginning – Essential The war ends and the survivors deal with the aftermath. And so after all the insanity, darkness and at times, frankly, bullshit, Animorphs makes its final case for what it always was at its core; a story about the cost, necessity and folly of war. An interrogation of what is justified and what isn’t without any easy answers. An examination of the different but always profound ways that war affects the survivors. A series that sits with discomfort in its final moments before pivoting to a cliff-hanger that on release frustrated millions but now looks kind of bold, if still a little maddening in its lack of resolution. But really, Animorphs wraps up its core story in powerful, satisfying, thought provoking style while leaving us with the beginning – and maybe end – of a whole new one that to date exists only in our imaginations. It’s a great ending to a great if uneven series, that remains kind of astounding in ever being allowed to exist at all.  This is the final part of an ongoing Animorphs retrospective - check out Part One, Two and Three. Not long after finishing the final Animorphs book, I was asked what I could read now to fill the gap. A few suggestions were thrown around – other YA or middle grade classics, other long running series that are easy to get lost in over an extended period of time. But Animorphs offered a very specific proposition with no real comparison. A series I was obsessed with as a kid but never finished, a series that still holds up to an adult audience, that is lengthy but has a very defined ending. Fundamentally, the opportunity to finish a story I first fell in love with some twenty-three years ago. No, replacing Animorphs will not be possible. Nor should it be. Most of the books in the second half of the series were totally new to me. There were one or two I did read as a kid, but not as frequently as a lot of the earlier books and as such the only real memories of them I had were fractured and vague. That said, I couldn’t pretend that the endgame was a total surprise. Over the years enough major plot points had been spoiled in casual nostalgic conversations that that was never going to be the case; I knew who died, I knew what the final moments of the series were, I knew roughly how the war between the Animorphs and the Yeerks ended. But honestly, the knowing didn’t do a lot to change the exhilaration of those final books. Weirdly, the series I was most reminded of was The Wheel of Time, another long running classic that I embarked on a complete read of a few years back, another series with several rough patches and a complicated final legacy. For so long in WoT nothing of note really happens, so when the final four books slam down the accelerator and the endgame hits, it’s impossible to be ready for it and you’re left hanging on trying to keep up with the sudden, drastic change of pace, the feeling that the author has thrown off shackles, whether self or publisher imposed, and just gone for broke. The last stretch of Animorphs is like that. The meandering of the thirties continues into the forties. There are a couple of good books in there, but nothing that really stands out like any of the early classics. Then we hit 45. We start with a classic, high stakes Animorphs set up that you naturally assume will be defused to bring us comfortably back to the status quo. Except it isn’t. A handful of pages into the book, a game changer is dropped on you as for the first time an Animorph is forced to tell their family the truth, setting in motion a chain of events that leads to even more gasp-out-loud moments. By the end of that book, nothing will be the same again. The next couple don’t exactly commit in the same way. There’s some progression and a definite sense that everything has escalated, that there’s no way back now, but the sheer scale of 45’s shift isn’t replicated. Not just yet. Reaching the final Chronicles book, The Ellimist Chronicles, was a bit frustrating in the middle of an apparent move into endgame territory, but it was another great read, a top sci-fi novel in its own right with some wild, terrifying, fascinating ideas at the core of it. Following that, 48 is technically a standalone, but ultimately serves as a kind of coda to the seminal David Trilogy back in the series’ roaring 20s. Given how perfectly the David Trilogy ended, this would seem ill advised. Given how off-the-wall this book starts out, even more so. Then we hit the ending, an ending that somehow manages to make David’s already troubling story even more messed up. The last six books are very much one serialised arc and it’s here that any lingering pretence of Animorphs being just a children’s series is thrown out the window. I guess Katherine Applegate and Michael Grant figured that by this point the ones still reading were the hardcore fans who were all in for the body horror, existential dread, terrible moral choices and emotional devastation, because that’s pretty much all you get for these last few books. 49 looks at 45 and basically says ‘I see your massive game changers and I raise you everything that’s about to happen in the next hundred and fifty pages’. I read that book open mouthed, stunned as every character’s life was upended, in some cases for the best, in other cases decidedly not. As plot threads seemingly forgotten near the start of the series were returned to, as character arcs reached culminations. This basically didn’t let up as I tore through the last few books. The goofy humour and pop culture references of the earlier books were all but gone, replaced by discussions of war crimes, of how much bad you can do and remain on the side of good, whether you can sacrifice thousands to save millions. There is no attempt to soften the characters in these final books and while there have been plenty of moments throughout the series that left me staggered at the fact that these are n theory for kids, the conclusion left me wondering just how I would have dealt with it at nine or ten. 53, the penultimate book, of course ends on a cliffhanger. I finished that one and went back and forth over whether to dive straight into the finale. I had cleared the whole next day for it and felt that I still had to digest what I just read (anyone familiar with the series will know 53 is the real climax). I wanted to space it out a bit, knowing that once it was done it was done. But all the same, I needed to know. That night I watched TV with my housemates. Did normal stuff. Then, when everyone went to bed, I poured myself a whisky and sat up reading alone. I woke up early the next morning and continued. I took breaks throughout the day, but returned until, that afternoon, sitting on my front porch, I finally read the last page of Animorphs. I didn’t feel a lot in the moment. I went for a walk. I returned home. Lay on my bed staring at the roof. I started reading articles about the ending then put them away, unable to yet grapple with it. Slowly, my feelings emerged. The ending isn’t perfect. But it’s good. It’s really good. It leaves you with big, gnawing, frustrating questions, particularly in its infamous cliff-hanger. But the truth is, it resolves everything it has to. It wraps up all the arcs we’ve spent sixty-two books following, and it does so in a way that proves with brutal clarity that Animorphs, for all the silliness and plot holes and filler books, is in the end a clear eyed but humanistic look at what war does to everyone touched by it. Which is all of us, even if we don’t realise it. There are no easy answers at the end. No hand holding, guiding us through the difficult choices the characters made. The final books force them, and us, to sit with the ambiguity of it all and my god I love that. In a time where many authors trip over themselves to shove unmistakeable moral messages into their books, Animorphs leaves you to make up your own mind on whether its central characters are justified, or whether there can ever be a justification for what basically amounts to genocide. We see beloved characters make choices very similar to ones condemned earlier in the series, and we have to just deal with that. Here's the big truth, the thing I only now fully understand about this mass-produced 90s series most famous for its tacky covers: Animorphs was never really a wish fulfilment fantasy, a superhero story or a disposable diversion for kids even though at times it wore the trappings of all those things. It's a tragedy. Not because it ends with everyone dying or the bad guys winning or anything that overt. Because we see our heroes win, and then we see what winning does to them. In The Lord of the Rings, Frodo tells Sam ‘we set out to save the Shire and it has been saved, but not for me.’ The ending of The Return of the King has always stuck with me for reasons best summarised by that line, for its sense that there is no real reward for Frodo. He gets what he wanted all along only to find that he can’t enjoy it anymore. He's too changed. That’s where Animorphs leaves us. Even the concluding cliffhanger, the specifics of which I won’t spoil here in case all of this has somehow convinced you to give the series a crack, underlines the fact that war might now be the only thing these people understand. And of course. It's not until the final books that the series directly addresses the fact that they will never, ever get back the innocence they lost the moment they walked through an abandoned construction site and accepted a call-to-arms from a dying alien. The Animorphs save the world by sacrificing their souls. And the implications of that are left for the audience to process. I don’t have much else to say about Animorphs. Four blog posts, a reading guide and a two-hour lecture to my reluctant housemates are collectively more than enough. But I guess what I want to conclude with is this; for all the garbage books and frustrating logic leaps, I am so glad that a bout of nostalgia earlier in the year led me to re-read this series. Sometimes your fond memories of something you loved as a kid don’t match the reality of that something. But sometimes the reality is even better.  This is the third part of an ongoing Animorphs retrospective - check out Part One, Part Two and Part Four. Learning as a kid that most of the later Animorphs books had been ghostwritten, I felt betrayed. But this, of course, was before I understood that TV shows, among many other long-form stories, are written by multiple people with one showrunner overseeing the narrative. Animorphs’ development was only unique for its medium and even then, not so unique for the 90s heyday of Scholastic Book Clubs and series with upwards of fifty instalments released monthly. Coming into my re-read, I wasn’t bothered by the ghostwriting of it all. But now, three quarters through and well into the era of the ghostwriters, my feelings are mixed. With every new book that does absolutely nothing to advance the plot or characters (and in some cases actively impedes them), I get a little more frustrated. It doesn’t help that it’s in the many lightweight filler books where the ghost-writing is the most obvious – a lot of the darker, more plot heavy instalments are as good as if not better than any highlight from the early days of the series. For example; book 33, which absolutely kicked me in the heart. The Animorphs discover that the Yeerks are perfecting an anti-morphing ray that could force them to reveal their human identities. So they come up with a pretty clever plan – get Tobias, who is trapped in the body of a hawk but has since regained his morphing abilities, to morph Andalite (the alien race the Yeerks think the Animorphs are), demorph to bird in the presence of the Yeerks then let himself be captured. The Yeerks will use the ray on him, not realising that bird is his true form, and when he doesn’t change, they’ll assume their ray doesn’t work. At which point the Animorphs will mount a rescue mission and “accidently” destroy the ray. It initially works, but when the Yeerks realise the ray isn’t doing what it’s supposed to, they start straight up torturing Tobias. And that’s… the whole book. Tobias slips between his nightmare reality and hallucinations that are by turns confounding, gut-wrenching and beautiful. He’s rescued in the end, but over the following books it’s clear that he’s been profoundly damaged by the experience and nobody knows how to help him. Then in book 34 Cassie has to share her mind with the consciousness of Aldrea, the protagonist of probably the best Animorphs book, The Hork-Bajir Chronicles. HBC meant so much to me as a kid that I was really looking forward to this quasi sequel, which I never got up to back in the day. It didn’t disappoint, building beautifully on the themes and characters of the earlier book, advancing elements of its narrative without undermining the bleakness of its ending. Experiences like this are the best thing about revisiting this series as an adult – getting a kind of belated catharsis for stories that meant a lot to me growing up. But the rest of the books in this quarter are a lot more variable, quality-wise. Even the generally good ones are beset by plot holes and logic leaps, creating a sense that the narratives weren’t really thought through. Which is understandable given the publishing schedule, but considering how solid the plotting was to begin with, it’s disappointing. It was this issue that led to the first real case of me being let down by one of the books I loved as a kid. I always adored Megamorphs #3: Elfangor’s Secret, which sees the Animorphs trailing a time travelling Yeerk throughout history attempting to stop him from altering major battles in order to make the human race more susceptible to invasion. Throughout the book the Animorphs all get killed in various horrible ways only to reappear after the next time jump for reasons too complicated to explore here. I always remembered the harrowing image of the back of Jake’s head being blown off as he attempted to cross the Delaware, or of Rachel torn in half by a cannonball at the battle of Trafalgar. Reading it now, it’s this book more than any other that engages most directly with Applegate’s central theme of the cost of war. But it ends on the Animorphs making one of their patented horrifying moral concessions, only for it to not land because there are so many clear alternatives. It makes what should be powerful and haunting feel hollow. And it isn’t the only recent example of the Animorphs jumping to the most extreme, morally dubious solution despite the several obvious better ones. If you’re being charitable you could argue that the kids have become so desensitised that more palatable options don’t occur to them, but I don’t buy that. It feels like the series is trying to maintain its through line of moral ambiguity despite the rushed writing process meaning that said ambiguity isn’t thought out the way it once was. Which dulls the impact. A similar leap underpins book 30, which concerns Marco grappling with the choice to kill his mother, who is infested with one of the most powerful Yeerk generals. But there are so many other possibilities that the writer just seems to ignore and so when the moment comes for Marco to push his mother off a cliff (she survives, but still, rough) I just couldn’t quite get on board with it as the act of soul-destroying necessity it was clearly intended as. At this point in the story she’s a fugitive – why not kidnap her for three days and starve the Yeerk out of her head like they did to Jake way back in book six? A later book, Visser, does go some way to offering an explanation, but it’s an explanation tied directly to changed circumstances and as such not actually pertinent to the choices made in 30. Furthermore, instalments I might previously have found charming or entertaining started to grate. Take the book in which the Animorphs, well, discover Atlantis only to find it’s populated by mutated monsters who turn shipwrecked sailors into macabre museum displays. Taken in isolation it’s a fun, creepy read with some cool ideas. But this late in the game, every book that doesn’t contribute to the overall arc runs the risk of being annoying, no matter how well it might work on its own terms. And none of this is even mentioning paperback bound middle-fingers like the one where the Animorphs discover the Yeerks are trying to use cows to eradicate free will or the one where Jake goes away and Rachel suddenly becomes a power-hungry lunatic who regularly refers to herself as ‘the king’. Some characters, like Marco or Tobias, survive the various ghostwriters largely intact. Others, like Rachel or Ax, see their personalities wildly vary from book to book, scarcely in any way that’s flattering. Oh, and there’s a deeply haunting book where Cassie accidently gives the morphing power to a buffalo and I still think about it way more than I should. Sustaining the early energy and quality of any book series is hard. Sustaining it over sixty books, many of which were written by one-off authors on a monthly basis? It’s astounding that Animorphs at this point in its run remains capable of all timers even if they’re relatively rare. Ultimately I’m enjoying the re-read too much for the issues to overly matter, but they do reinforce my belief that the best way to read Animorphs in a modern context is to get ruthless with which books you read and which ones you skip. I’m committing to reading them all, but I couldn’t in good conscience recommend anyone without a similar nostalgic love for the series do the same. The good stuff is brilliant. The less good stuff becomes more exponentially punishing as the story nears its end, worsened by how obvious it can be when somebody who is neither Katherine Applegate nor Michael Grant wrote it. But none of that changes how I feel about the looming end of my re-read. Fifteen books left. Fifteen until I finally reach the final instalment. In the past few months I have read forty-seven of these and somehow, frustrations aside, I’m not ready to say goodbye. But given I started reading this series in 1999, it’s probably about time I found out how it ends. My oldest friends still roll their eyes when I say the word Windmills. Which is fair enough, because at this point that word is synonymous with ‘pathological inability to let go’. Windmills was originally a novel I wrote in year twelve, which became a play which became a novel again which became a screenplay then a novel again and in between spawned all manner of sequels, spin offs and derivatives as I tried to find my way to a version that worked. The closest it came was the TV pilot adaptation that won the Ustinov in 2015, but even that ultimately never saw the light of day.