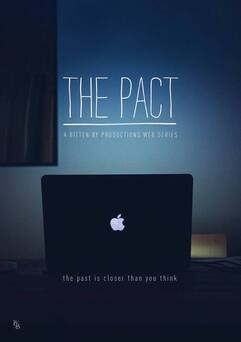

When talking about The Pact a while ago I alluded to the fact that it wasn’t my first foray into the world of web series. And for those five people who remember Bogan Book Club, it wasn’t even my second. The first is nowadays more a punchline than anything else. I don’t exactly remember where the idea for Phoenix came from, but at some point towards the end of high school I decided to make a no-budget web series shot in ‘artistic’ black and white to show off how serious it was, a web series that would follow a group of teenagers trapped in a house after a nuclear war. The concept was neither original nor terrible. The planned execution was the inverse. My initial idea was to shoot it with a group of friends from my hometown, none of whom had the slightest interest in acting. Or, for that matter, being part of it. The idea ended up in a drawer. Then, while involved in a play out in Warburton towards the end of year twelve, I floated the idea to the director, Sarah Ward; now known as the founder of the ever-expanding Misfit Theatre. Sarah and I became totally enamoured with Phoenix, taking my original scripts and building an epic mythology out of them along with a planned thirty episode arc that, when it inevitably went viral and made us all world famous, would be the springboard to a hit movie. Obviously none of that happened. We cast people who had been in the play and launched into filming without much of a plan. Which went about as well as you’d expect. This was a series shot on an old camera from which all uploaded footage was stretched and pixelated, edited on Windows Movie Maker in stolen minutes between work and uni. I vividly remember uploading the first episode to YouTube only to very quickly learn that strangers on the internet are not kind. I actually became that guy who made a fake account to rebut all the criticisms, as if anybody would go to such effort to defend a series ostensibly set after a nuclear war in which sunlight and trees were clearly visible out the window. But we kept filming. We got maybe a little better but it was hard to come back from those awful first episodes. And there were other struggles. Cast availability issues meaning that we would either have to sub in new actors and hope nobody noticed, or else come up with sudden ‘plot twists’ that revealed an extra person had been living in the house all along, conveniently revealed right as another character vanished. A combination of growing disillusionment with the project and the fact that, you know, nobody was watching meant that we stopped shooting with our sixteenth episode. That wasn’t the plan; I’m pretty sure at the time we had every intention of keeping going, but we never did. Over the following weeks there were half hearted attempts to pick up where we left off but time passed and lives moved on and before long Phoenix was squarely in the rear-view mirror – eventually even removed from YouTube to try and mitigate the inevitable humiliation should it be rediscovered. Over the years I attempted to reverse that. I still thought the idea had merit and that, executed correctly, it could be something really cool. The year after shooting the original episodes we got fairly far along developing a rebooted version with a new cast that would in theory make up for the failings of the original. Never shot, naturally. The year after that, I actually wrote the first in what I hoped to be a Phoenix novel series, which remixed characters and events from the original web version with the seeming benefit of no budget constraints. It didn’t work. The pace was lurching and I wasn’t able to inject the material with any more originality than it had had to begin with. Then, a few weeks ago, one of the old cast members got back in touch with the rest of us to point out that we never finished Phoenix. And between the jokes and reminiscing a vague idea emerged. What if a final episode was written that could wrap the series up? A final episode that could be shot and edited in a day, just like the old ones, after which we could all watch the whole series through, naturally with plenty of beers and laughs at our 2010 ‘acting’. Obviously this finale would never be released publicly, but rather exist as an excuse for the cast to get back together, have some nostalgic fun then a few chuckles at our own self-important expense. Recently I was having drinks with some friends and the topic of Phoenix came up. I immediately slipped into my automatic response of disparaging everything about it, only to be quickly shut down by the point that when you’re an eighteen-year-old creative you’re supposed to make bad things. That’s how you learn. And besides, healthy giggles at the badness of said bad things aside, there’s nothing to be ashamed of about trying to make something when you’re a dumb teenager. Hearing that really stuck with me. I’d never thought about Phoenix or even my shambolic early theatre writing that way before. I’ve always acted kind of apologetic when it comes to talking about old work but it’s only now I realise that I’ve got nothing to be sorry about. If I hadn’t made those crappy old projects, I wouldn’t have learned how to make the better new ones. So anyway; call it sheer stupidity, call it a belated tribute to an early learning curve or a chance to do something fun with old friends again, but whatever the case we’re finally finishing Phoenix.

0 Comments

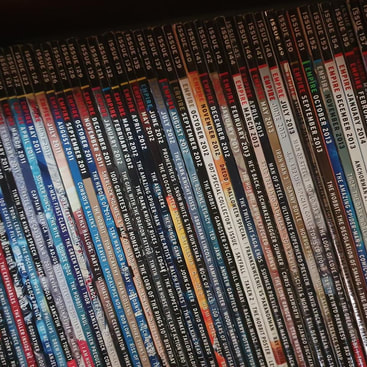

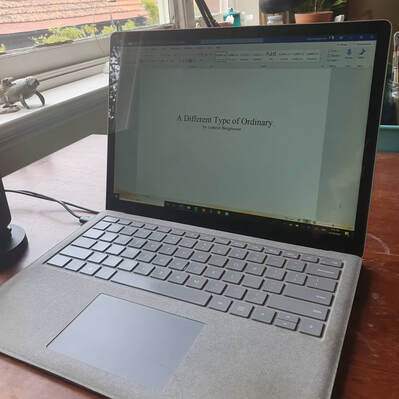

This week the last issue of Empire Magazine came out. For anyone not obsessed with film during the 2000s, Empire was the best movie magazine going around, packed with insightful reviews, features on upcoming films and fascinating retrospectives on classics both revered and obscure. I got my first issue of Empire when I was eleven and haven’t missed one since. That’s eighteen years I’ve been buying it. As a kid fixated on film, the discovery of Empire was seminal for me. Through the magazine I discovered so much about not only the history of the medium, but what went into creating a film, the signature styles of different directors and of course, what made a good movie. It also, almost certainly, introduced me to a few favourites that I was way, way too young for. I doubt I would have secretly watched The Silence of the Lambs, The Godfather, The Exorcist and so many more if Empire hadn’t regularly made the case that to have not seen them was to be missing out on some of the fundamental pillars of what made modern cinema. For most of my early teenage years Empire was my bible. I would bore my friends with facts about the original King Kong or else announcements about what that Tarantino guy was doing next. I would devour every new issue and come out of it feeling a combination of informed and woefully uneducated – there was always some essential new classic that I would have to get my hands on and watch just so I could consider myself a real film buff. Empire also taught me a lot about criticism. For the first couple of years I read the magazine, I took its reviews as gospel. I was shaken when Troy, a film I adored, got a withering review – was I wrong or was Empire? After a couple more similar cases the seeds were planted for my eventual realisation that there isn’t really such thing as right or wrong when it comes to your feelings on a movie, that different works appeal to different people for different reasons and that’s okay. That even the opinion of the most insightful, well-reasoned critic is still just an opinion. Slowly the relationship changed. The time I was religiously reading Empire coincided with the growth of the internet as the most convenient place to access film news. By the end of high school Empire was no longer my first port of call to learn about upcoming releases, but I still clung to it for the massive behind-the-scenes features and of course, the reviews. Then came my early university discovery of websites like the once-great-now-grim A.V. Club, or Den of Geek; websites that provided reams of daily extensive analysis completely for free. Soon I was writing my own criticism and analysis. I worked for Den of Geek and hosted a popular movie podcast. Now on the ‘inside’, my perspectives on the job of pop-culture writing changed. I still bought every issue of Empire, but its importance to me as a resource had slipped, as had my perception of its authority. Every now and then it would have a great feature or two, usually retrospectives of some sort, but for the most part the reviews seemed truncated compared to the in-depth essays available online, while the bulk of the pre-release coverage was given over to Marvel films and other blockbusters that already consumed so much oxygen. In a crowded market of film discussion, Empire no longer stood out. I don’t make this point as a criticism of the magazine. Considering the type of content Empire provided was one of the first things to become popular online, it’s astounding that the magazine lasted as long as it did. But from the perspective of a long-time reader, it was increasingly clear that Empire was struggling to keep up and remain relevant. It felt at times like the magazine was veering wildly between identities; by turns trying to rebrand itself as a more niche exploration of cinematic obscurities or a loud, splashy celebration of all things Marvel, Star Wars and DC. The content became more political, adopting in parts the tiresome online mentality that a film should be judged more on what it had to say about Trump or whatever than whether it was actually any good. All of this was understandable, given the nature of the magazine’s myriad online competitors. But it didn’t do a lot to make Empire’s case as being essential in a crowded market. Several times over the past few years, I found myself wondering why I still bought the magazine. I always did, but more often than not I’d give it a cursory skim then leave it on my desk, meaning to read it more thoroughly only to find that the next one was already out. But even with all of that, the news of Empire’s end hit hard. I think sometimes you need to lose something to realise what it meant to you. My relationship with the magazine might not have been what it once was, but the fact that it was still going and I was still buying it provided a direct link to not only my childhood, but to the time when I first understood that telling stories was what I wanted to do with my life. Here, ultimately, is the part of this post that would be hyperbolic if it wasn’t true; I don’t think I would be the person I am today without Empire. So much of my identity as not only a film buff but as a writer and, at one point, a critic was shaped by reading that magazine in my formative years. Empire opened my mind and introduced me to countless films I never would have watched otherwise. It fostered in me a deep and abiding love for the history of cinema, a respect for the classics and an excitement for the new. It taught me that there are different kinds of greatness; that a gory zombie film can be just as brilliant as a worthy historical drama, that what a story is matters less than how it’s told. At its best, Empire was a celebration and conversation about all of cinema, a publication that would give just as much adoring page space to A Nightmare on Elm St as Citizen Kane. And in guiding me towards so many of the stories that would inspire me, it directly helped me find what kind of storyteller I wanted to be. For eighteen years, every month like clockwork, I would buy the new Empire. This marks the last time I’ll ever be able to. That, along with everything the magazine meant to me, felt worth writing about.  I haven’t exactly been unproductive during lockdown, but it has sucked for creativity. I’ve been kept in work by a couple of TV projects along with edits on The True Colour of a Little White Lie – then of course there were my twin lockdown projects, the podcast Was It Worth It and web-series The Pact. But those were born out of an almost desperate need to make something during this time, projects that never would have existed if somebody hadn’t eaten a pangolin in Wuhan. But even before lockdown I was struggling a bit creatively. I got about halfway through writing what would have been book three in the Maggie series, only to realise that it was not working at all. And meanwhile, I was repeatedly trying and failing to make any headway on Madison’s Masterpiece, my planned sequel to True Colour. Eighteen months ago, these struggles wouldn’t have mattered much, at least not to anyone apart from myself. But a couple of months back my publisher called to ask how the sequel to True Colour was going. I made some noises about how I was still discovering it then flippantly said ‘but I’ve got time’. The brief silence I got in response undermined that assumption. I had time, yeah, but not enough to waffle and chase different creative impulses. To know that we had a book in good enough shape to be published a year after True Colour, I would realistically need a draft before we rolled into 2021. While Madison’s Masterpiece was the frontrunner, I in fact had three different ideas for sequels to True Colour that I’d been playing with. Masterpiece would have taken the Tana French approach of telling a different character’s story. Idea Two would have been a totally different story featuring protagonist Nelson two years later while Idea Three would have been more of a direct sequel to the events of True Colour. So I gave myself permission to, without throwing out any of the work I had done on Masterpiece, toy with working on Idea Two instead. And quickly the story formed; characters and plot points growing around a central theme of how sometimes we obsess far too much over being friends with people who are like us as opposed to people who like us. Something else that unlocked the story for me was embracing the fact that it was a sequel. In the earliest conception of this idea I’d figured I would include only oblique references to The True Colour of a Little White Lie, but as I plotted I realised how inauthentic that would be. The events of that first book would have been huge for Nelson; where we left him last time would absolutely define where we find him this time. So I started to write. And at first it was clunky. I felt rusty. Nelson’s voice, self-deprecating, naïve and occasionally petulant, seemed to come only in snatches that made me wonder whether this was the same character. But I pushed through slowly something resembling a book took shape. At around the halfway point I had to take a week off to focus on a different, more pressing project. At first I worried that this would compromise the flow but in actuality it had the opposite effect; when I came back to Nelson 2 something seemed to click into focus. Of course Nelson’s voice had changed, because Nelson had changed. Two years isn’t a long time for adults, but for teenagers the gulf between fourteen and sixteen is enormous. And because Nelson wasn’t the same person as he was in True Colour, I couldn’t write the story the same way I wrote True Colour. I started worrying less about articulating or narrating Nelson’s emotional state at every point, like I had in the first book. I picked up the pace, jumping more ruthlessly between key moments. And weirdly, this let me relax into the book a little more, letting the moments where the characters just hung out and talked and enjoyed each other’s company, the moments that underlined my theme, breathe and develop naturally. There’s one passage towards the end of the book that is among my favourite things I’ve ever written, a reflection on friendship and impermanence that is unlike anything I have ever put on the page before. And it was from this passage that I found my title, a title that both reflects The True Colour of a Little White Lie and gives this book its own separate identity – A Different Type of Ordinary. But the awkward early stage of the writing process bothered me. I might have found my rhythm towards the end, but when the time came to read over it, would the first half work at all? Honestly, it’s hard to say. I started reading with the understanding that I would probably have to cut a lot. The first draft had come in at 75,000 words – longer than The Hunted (67k), True Colour (53k) and all three Boone Shepards (40-60k). I figured I would conservatively cut about 5000 words, maybe 10,000 if I was really ruthless. I cut 17,000 words. And that was only after a first read. Books teach you how to write them. I always struggle how to answer when people ask me about my process because the process is different every single time. Even two books in the same series can’t be written the same way because for them to have any integrity as stories they have to have their own concerns and identities even as they complement each other. True Colour is a highly interior book, the story of a lonely kid coming into adolescence and slowly learning that everyone else around him is just as much a person as he is. Different Type is the logical next step. It’s more rife with drama and incident, and as such there is less room for the reflections and internal hand-wringing that characterised True Colour. I had to write the book to figure that out, but I’m still not sure it works. For now, as I return to the Maggie-verse to try and make the sequel to The Hunted even better than the first, I’m honestly just happy to have written something new, something messy and heartfelt that is likely a long way from perfect, but at least comes from somewhere real. Time will tell if that’s enough.  This is the final part of an ongoing series about the making of The Pact - links to the previous parts are below. Part One Part Two Part Three Part Four Part Five *** A few years ago, not long after Boone Shepard was released, I decided to try and read the finished book in its bound final form. I didn’t get very far. I was still too close to all the work that had gone into it to see it as anything more than a chore. In the end it took me over a year after release before I could read Boone Shepard again and conclude that actually, I was proud of it. As such, it wasn’t a surprise that my first marathon viewing of the whole of The Pact, edited, mixed, graded and finished, wasn’t a lot of fun. All the way through I fretted about the pace, the picture quality, aspects of the scripts and performances. But I had also only just come out of those long hours in the edit suite, watching every episode over and over to make sure it was as good as it possibly could be, that there was nothing left we wanted to change. After that, there was no way I could view it with anything like objectivity. So we geared up for release. Pete, Rose and I all did interviews. Reviews began to come in, mostly positive. Farrago called it “confident and bold”. TheatrePeople described it as a “wonderful online twist of the usual neo-noir narrative format”. The Independent Arts Journal rightly raved about Rose’s work, but were critical of the structure of some of the early episodes, suggesting that the conflict was contrived to give each episode a narrative shape. ScreenHub, for their part, felt that we’d missed the mark. Some of the criticisms I found unfair or at least could explain the choices that led to them, but that’s the nature of the beast. You can’t walk an audience through all of your intentions so ultimately the work has to speak for itself, for better or worse. If I’m honest, I probably expected a bigger response across the board. Maybe the choice to release the episodes daily instead of in one hit was a mistake, but we really did want the individual chapters to get their chance to shine. Still, from the start there just wasn’t all that much engagement. Across Instagram and YouTube the views were okay, but they peaked in episode one and never hit the same heights again. We did what we could to promote it, including regular Instagram Live events where various members of the team (writers, director, editor, producer) chatted to key cast members, and those got pretty decent viewer numbers, but overall the series didn’t blow up the way we ideally would have liked. Which isn’t to say that I was expecting a million views an episode or anything, but I guess one of the realities of putting so much time and work into a project is that you can begin to believe that the ways in which it has consumed your life will translate to it striking a chord with others. That rarely happens, especially when your sole means of promotion is your team posting about it on Facebook. Of course, there’s an elephant in the figurative room of this blog, one that you likely became aware of around the time I mentioned the first episode getting better numbers than the rest. Some people I’ve spoken to say that the first episode wasn’t strong or involving enough to keep them watching, and that’s probably fair. It was a tough nut to crack, and we had to try and crack it without fully knowing how to tell a story in this way, something we could only learn by doing. Without the budget or time to revisit things again and again, in the end we could only do what we could do. And while that’s not a blanket excuse for any of what might not work in The Pact, it’s the reality. We made this in weird circumstances without any money because we wanted to. Every single person involved went above and beyond what I could have asked of them to bring the show together. And if that wasn’t enough, well, I can’t say what would have been. I do think, for whatever it’s worth, that the show finds its feet as it goes on. There was unquestionably an element of trial and error in the early stages, as we got a feel for the medium and the story, but once we found that balance the show, for me, hits a stride that I believe really works. If people found the first episode a struggle then I wish I could push them to watch at least a few more, because a lot of the feedback we've had from people who finished the series indicates that as it finds its momentum and voice it becomes a pretty compelling binge. None of that is to say that an audience should feel obligated to persevere if they simply don't find it engaging, but knowing as I do how great some of the performances and scripts are in the back half of the series, I do hope that more people give it a shot in the weeks and months to come. There’s so much about the series that I’m proud of without qualification. On a personal level, I think my script for episode seven rocks. I think the performances, especially from our four most important players (Rose, Jimi, Greg and Tatiana), are stunning. Episode twelve is brilliant, and as the climax of the series I couldn’t have expected better work from the team. I’m also proud that during this weird and, yes, unprecedented time we made something, something ambitious and complicated with a lot of moving parts that everyone committed to a hundred percent. I will always love collaboration and The Pact was a great one. How can I not be grateful for the fact that I got to spend a big chunk of lockdown telling a story with my friends? It was challenging and it wasn’t perfect, but to briefly borrow the premise of my other lockdown project (which, incidentally, featured a lengthy post-mortem of The Pact), it was entirely worth it.  This is the fifth part of an ongoing series about the making of The Pact - links to the previous parts are below. Part One Part Two Part Three Part Four *** Originally I’d planned to write a full blog about the marathon shoot that wrapped The Pact, but on reflection I don’t know that there’s too much of any value to say about it. Not from my perspective anyway. I know it was grueling and intense for Pete and Rose – three of the series’ most intense episodes were shot back to back in one day – but for me that week and a bit in which the last half of the series was shot was a succession of updates on how each episode had come together. It was an absolute change of pace, after the drawn out filming of the early eps, but by this stage the team knew what they were doing and worked efficiently. We hadn’t quite plunged into lockdown 2.0 at that stage, which meant that at least for a little while there John, Kashmir, Pete and myself could all be at the editing sessions. Together we watched and discussed every episode, as John worked incredible magic to make our series function before our eyes. Seriously; we were all wowed by how quickly he could piece the episodes together, how it took him mere seconds to make cuts or swap in footage from other takes. Par for the course for a professional editor, I’m sure, but for us plebs it was pretty exciting to watch him work. The process did take longer than we expected. Every editing session would start with a rough aim of where we planned to get up to that day, but we never quite managed it, especially as the series went on and the episodes became longer and more complex. For the most part there weren’t any major catastrophes. There were inconvenient discoveries along the way; like how the best take used for one episode had an object in frame that wasn’t present in the parts of the other take we were also using. In all those instances, John confidently and with seeming ease found ways around them. If there is one big lesson I’ve taken away from The Pact as a whole (and there are many) it’s how essential a good editor can be. And we had a great one. There was also a bit of a looming deadline, or so we thought. After all, the reasoning behind the marathon shoot and the big whole-cast rehearsal had been the fact that, as we came out of lockdown, the novelty of the series and arguably its most interesting selling point, the fact that it was something made almost entirely remotely during lockdown, lost value. Of course at that point we didn’t know that we were about to plunge back into Stage Four restrictions. As we went on I found myself getting more and more ruthless with what would be cut. We (I) came up with some wildly inappropriate terms for our satisfaction when episodes came in under five minutes, which was the aim for at least the first half of the series. Splitting the difference between showcasing the subtleties of the scripts and performances but keeping the episodes punchy was a real challenge, but as we went on I was taken aback by how many moments that had seemed essential or justified on the page didn’t need to be there on screen. Occasionally there would be the distinct thrill of realising that whole minutes could be ripped out of the episode and actually make the story work better. Many of the later episodes, in their rough-cut form, were well over ten minutes. By the end of the edits, only the finale retained that length. The best example of how this ruthlessness could end up serving us had to be episode nine, the monologue episode written by Damian Robb and conceived as a chance for Rose to show off just how good she could be alone on camera. The performance and the script were fantastic, but the episode was too long (ten minutes) without enough crucial new information at a point where the story had to be speeding up and delivering answers. We agonised over how to handle it, torn between wanting to show the full extent of Rose’s incredible, one-take work but knowing we needed to up the pace. Of course, given the episode was done in a single shot, we didn’t have the same luxury of being able to cut between moments as we did in others. Or so we thought. As we grappled with what to do, an idea was thrown into the mix; what if we did cut, harshly and jarringly, between key moments in the performance? We decided to give it a try and quickly we were blown away by the result. The cuts not only highlighted Rose and Damian’s work, but created the sense of coming in and out of consciousness, as Morgan, who by this point has fully descended into alcohol abuse, absolutely would be. The episode being framed as a filmed message for Brett meant that it also gave the impression of Morgan leaving multiple rambling messages one after another. It was a case where losing half the material actually allowed the episode’s role in the story to shine, underlining what it was trying to say while getting the length down to five minutes. Upon release it was one of the most well received episodes, referred to in one review as ‘five minutes of gold’. Those hours in the edit suite, now that we’re on the other side of the series, are probably among my favourite memories of the whole project. Working together with good friends, pushing through disagreements and making discoveries as we all did our best to create something we could be proud of, something that had slowly grown into a lot more than the quarantine time-killer it had been conceived as. Between edits we had long conversations about all sorts of things, ate pizza and and left every night with a real feeling of excitement about what we had on our hands. Meanwhile, covid case numbers grew and strict rules returned to Melbourne. Our worries that the series would be released too late to capitalise on the circumstances started to look grimly unfounded. Almost matter of factly, we settled on a release date after much back and forth over when the best date would be. The finished episodes went to reviewers. After all the work we’d done, the release of the thing felt almost like an afterthought. I don’t think I even remember the moment when we knew that the series was fully locked. So, after everything, we were finally done. The project that had been far bigger and more stressful than any of us had planned for was finished. All that was left was to see how it would be received.  It’s odd to look back now and think that the lifting of Covid restrictions was looking to be a problem for us. Obviously not a massive one –the timeliness of your web series potentially dissipating due to an improvement in state-wide circumstances is such an absurd first world problem that it can’t even fairly be called a first world problem. Nonetheless, it was a factor; The Pact was designed to be an example of the good work that could be made even in trying circumstances. The series not being set during the pandemic would certainly help it maintain a degree of timelessness, but it wouldn’t have the same impact once the lockdown was well and truly over. And with seven episodes filmed and seven more to go, restrictions were lifting at a speed that made us think we had to pick up the pace or be relegated a relic of a time everyone wanted to forget. What sweet summer children we were. It was Pete who suggested cheating. Yes, part of the sales pitch of The Pact was that it was written, rehearsed, filmed and edited entirely remotely, but if more than five people could be in a room then maybe there was an opportunity for us to increase the pace of shooting without sacrificing the quality. So Pete called with a pitch; a big, all-day, in-person rehearsal. We’d get together the cast members with remaining episodes to shoot, read through the scripts, then collectively workshop and rehearse everything left. Pete’s reasoning was that, without the barrier of a screen between the actors and director, more could be done in a shorter span of time. Then, striking while the iron was hot, the remainder of the series would be filmed over the following week; one or two episodes a day, wrapping the whole thing in less time than it had on average taken us to get one episode done. It was an ambitious plan, one which had my complete support. Patience has never been a virtue of mine, and if I’m honest the slow pace of production until that point had been a little frustrating. After all, the series was intended as something that could be turned around fast, but then it was also intended to include only six episodes and be made without a director, so my total lack of realistic forethought was pretty well established by that point. The date was locked in and we pulled together as much of the team as we could. Laila Thaker and Enzo Nazario had already shot their episodes, so they weren’t present, while Michelle Robertson was yet to shoot hers but wasn’t available. Rose, of course, was there – meeting Pete in person for the first time after many hours of filming and rehearsing together. Chris Farrell, who still had one episode to shoot as Morgan’s brother Tim, was there, along with Greg Caine – who had already shot his first episode as Morgan’s conniving father Jack Carlin but had one yet to go. Otherwise we were joined by Justin Anderson, recently cast as the duplicitous Uncle Gary, Tatiana Kotsimbos, who plays the key role of Jade, and of course John and Kashmir, who had been helping to guide the project from the start. The one cast member with material yet to film who couldn’t be there was James Biasetto, who lives in Sydney and as such had a pretty decent excuse. It was the first time the majority of The Pact team had been together in a room and, like Pete and Rose, the first time several of those people had met in person. There was a definite sense of excitement as we settled in for the table read that would kick off the day, starting from episode six. Seven had already been shot, but Pete felt it would help to hear it anyway, just to aid the flow of the narrative. So Rose and Greg, with the dialogue still fresh in their heads, got to it. And just… holy shit. Episode seven was an important one for me. As the episode where Morgan faces off with her father and in the process starts to understand just what she’s up against, it’s the midpoint of the series and several writers had expressed interest in taking it on. But I’d clung to it for a couple of reasons; partly because Jack Carlin is a character who has appeared in other works of mine and I strongly felt that I needed to at least write his introduction to The Pact, but also because when you’re doing the showrunner job that I was, there isn’t a huge amount of opportunity to really write. Let me explain just a little bit. Episodes one and fourteen were the hardest to crack because of all the heavy lifting they had to do. One of the major reasons we re-shot episode one several times is because it had to establish Morgan as a character, introduce the mysteries, set up the themes of the series and do all of this while making an audience invested enough to watch the next episode. It was, not to put too fine a point on it, fucking hard. The same went for fourteen, which had to resolve everything in a satisfying way, make sure the final puzzle pieces of our mystery fit neatly without any egregious dangling questions, and still be an engaging piece of drama in its own right. There was very little fun to be had in either of those episodes. Seven, though, was pure story and character, and I adored writing it. I’m so proud of that script and seeing Rose and Greg perform it live was a special privilege. They sat at either end of the table, wielding their dialogue like weapons, constantly attempting to outmanoeuvre each other, all the while showing just how much hurt and compromised love there was between them. The rest of us sat in stunned silence, riveted and uncomfortable, feeling like we were spying on something raw and ugly and personal. I think in that moment the full scope of what we were doing began to dawn on me. The fact that, in bringing on board the range of brilliant people we had, The Pact had become something far more than a little isolation project to keep us all occupied. What was taking shape was a complex story of very human failings, a story without villains, a compassionate but honest look at addiction, guilt and consequences. That day was, in the end, overwhelming. Rose and Greg’s stunning performance set the tone and after that we worked through every episode slowly and meticulously, following it up with lengthy discussion about what we felt was going on for the characters, what the meaning of that particular chapter was. By the time the read was done, the day was almost over. We moved into some workshopping and one-on-one discussions, but we were out of time for the planned rehearsing. Which, in the end, was fine because in bringing as many of us together as we could the day had achieved its objective. We all, myself included, walked away with an increased understanding of this thing we were making but beyond that, with a unified sense that we were making it together. That despite the separation inherent to creating something in a pandemic, we were a team working to realise something special. Now we just had to finish the thing.  A little bit about Peter Blackburn. We first met working on The Trial of Dorian Gray. Kashmir introduced us, thinking that Pete would be a great fit for that script. His reputation preceded him and I went to that first meeting apprehensive, suspicious that he would be a haughty wanker looking down his nose at our little indie theatre project. Not because anything I’d heard about him indicated that this might be the case, but rather because he is held in such high esteem in the Melbourne theatre scene that it was hard to imagine he would want any part of our project without lots of money and lots of changes. It took maybe two seconds for me to be disabused of that stupid notion. Sometimes you meet people with whom you instantaneously connect and that was one of those times. Pete is not only one of the kindest people I’ve ever met, but one of the wisest, most committed, and most formidably talented. He works without ego; committed only to the realisation of the project as best it can be. He has a singular ability to draw incredible, layered, natural performances out of actors and tends to finish a project with the fierce loyalty of everyone involved. Pete deserves the same evaluation I have of Rose; if you can get Pete Blackburn to direct your play, get Pete Blackburn to direct your play. Or, in this case, web series. That the idea of bringing Pete on board didn’t occur to me earlier is indicative of my own idiocy. I’d even sent him early scripts and outlines for feedback without ever thinking to suggest more direct involvement. Pete, after all, had been on board to direct our planned next show, Three Eulogies for Tyson Miller before lockdown happened, and with The Pact more or less replacing that play in our schedule, moving the whole team over probably would have made sense. It was after we decided to reshoot the first ep and I called Pete for feedback about what we’d gotten wrong that a very obvious realisation clicked into place. At some point in that phone chat the idea of Pete directing the whole series was raised and that was that. He connected up with John, Rose and the rest of the cast, and the ball started rolling. Episode one would be reshot, and then they would roll straight on to the rest of the series. And under Pete’s guidance, we wouldn’t have a repeat of the same issues with episode one. Well, not a repeat anyway. As the first cut was turned in of the reshot episode one, it became clear that this would be a particularly tough nut to crack. The problems, I stress, were not the direct fault of anyone involved. It was a confluence of minor things that all together meant the episode designed to kickstart the series was not making for especially compelling viewing. The script needed a tighten. There were eyeline issues. Tonally it came off as too dour and downbeat. People say endings are hard, but I can promise you that they are nowhere near as hard as beginnings. After all, the challenge of ending well won’t matter one iota if your story hasn’t drawn in an audience, and it’s very tough to do that without a strong opener. The new version was a marked improvement on what we had, but another round of collating feedback illustrated that my reservations were not paranoia; the problems were problems. My reluctance to reshoot remained. This should have fixed everything. But then, if the me of two weeks previously was to be believed, this should have been an easy project. And that was proving to very much not be the case. Things got a bit heated as we discussed what to do about episode one. The consensus was largely against reshooting. At that stage I was more or less willing to accept being outvoted, but that didn’t change my doubts. Episode two came in and, while it was solid, it was hard to see it as proof that our concept overall worked. Episode two is very much a table setting instalment, paving the way for the fireworks factory without getting there itself. Which made me anxious to see three and four; three includes a major reveal that sets up the remainder of the series, while four works as a kind of climax to the ‘first act’ of the story. The two episodes were filmed back to back and so, as new scripts came in and I edited them, I waited. Some issues with three meant that four was ready first; it was sent through shortly after restrictions were eased enough for us to have some friends around to dinner. So, rudely, I stepped into my room to watch the cut. And in moments, we were vindicated. Four was brilliant. Chris and Rose infused so much anger, hurt and betrayal in their performances; a pay off to the tensions between their characters in episode one. They brought Kate’s searing script to breathtaking life, sending me running back to the dinner party overflowing with exhilaration. Kashmir felt the same, and that catapulted us into a bold new conversation. We weren’t convinced episode one was working. And at VCA I had been taught over and over that where possible, you should start the story as late as you could. So what if episode four became episode one? If we started with a showdown between two siblings, the culmination of years of unspoken resentment and hurt. What a statement of (accidental) intent that would be. There’s no harm in entertaining a bold idea, but it’s not always worth seeing through. The episode was satisfying because it followed from something we’d already seen. In isolation it would be a great acting showcase, but not an effective start to a series. Still, it proved what we were capable of and, to me, demonstrated exactly why episode one would have to be reshot again. This was now the standard we had to try and reach wherever we could. Three, meanwhile, had its own issues. The aforementioned reveal didn’t seem to be landing the way we thought. But in a case where the bold idea was exactly the right move, we came up with some drastic cuts that reshaped the episode into the gut punch it needed to be. Several people have now reported that three is the moment where they go from mildly interested to fully on board with the series. The first of many examples to come of how a good edit can transform something. Altogether we were well on the way. Five and seven were in the process of filming, as we were yet to find the cast member we needed for six. Everything was looking good. But as Covid restrictions lifted, the big sales pitch of what made the series unique began to lose relevance. The succession of trial and error coupled with the growing scope of the show had slowed everything down far more than we had planned. Which left us needing to work out a way to get as much filming and editing done as quickly as we could, without sacrificing the standard.  From the moment we knew what the plot of The Pact was going to be, there was only one option for our lead actor. I’ve known Rose Flanagan since we were both regularly on stage together in high school theatre. In fact, on some level I think Rose is at least partly responsible for my giving up on chasing the dream of being an actor – when you’re performing opposite someone as gifted as her, your own shortcomings as a prospective thespian become all too clear. Rose’s talent is formidable and, to paraphrase Jon Favreau speaking about Don Cheadle, I believe that if you can have Rose Flanagan in your project, have Rose Flanagan in your project. Rose has appeared in a couple of Bitten By shows, directed last year’s production of The Critic and as of very recently is a newly minted member of the Bitten By Productions committee. She also had a leading role in the largely improvised web series Bogan Book Club that I was part of back in my podcasting days. In 2016 she featured in another web series pilot I wrote that, despite high production values never went any further than one episode. I’ve worked with Rose a lot and yet I’ve always felt like she naturally gets pushed into the funny roles. Which makes sense; Rose is hilarious, but like most gifted comics she’s a fantastic dramatic actor as well, something I’ve always wanted to capitalise on. The Pact, then, felt like the perfect opportunity. I wanted to move quickly on filming. Already other creators were making and releasing isolation series, and while ours would not be set in the time of Covid, I was adamant that we wanted to release as soon as possible to capitalise at least somewhat on the fact that this was made entirely remotely by Melbourne artists during a particularly trying period for the industry. Once we knew what the full arc was going to be and once the scripts for the first couple of episodes were at a high enough standard, I figured it was time to get the show on the road. Casting too was yet to be completed, but we had a few actors locked in, and with Chris Farrell (who played Bruce in my play Springsteen) on board as protagonist Morgan’s estranged brother, we could get the first episode together and, if nothing else, at least get a sense for what we had on our hands. John and I went through a couple of options for what the best way to film would be. Recording an actual Zoom call was considered – the app even alternates between who is speaking at any given time, which in theory suited our purposes, but there were so many variables. A dodgy internet connection could scupper an episode. Plus, while doing it this way would be the most realistic, the show still had to be watchable. Blurry footage and laggy exchanges of dialogue would not make for an especially appealing viewing experience. This, by the way, would become the biggest point of discussion in the early stages of The Pact – where to draw the line between reality and entertainment. While naturally entertainment would always come first, given that the concept of the series was based around only video calls we had to maintain at least a foundational amount of fidelity to the form. My pitch for how to film was to get the actors to call each other on speakerphone with headphones in, but record directly into their webcams. This way they would look on screen like they were responding to each other, the recordings would be clear, and the actors would be able to react, if only to a voice. In the end, however, the consensus was that the actors wanted to see each other, and so more or less the same principal was used except the calls would be actual video calls allowing them to best bounce off each other. Practice recordings of the first episode seemed to indicate that this would work. By not recording the calls themselves but rather just each actor’s individual side, the quality remained relatively high. Going forward however, we would find that with vastly divergent equipment available to each actor, the filming process would differ depending on the circumstances. So we set a date to shoot episode one. It felt premature and a little thrilling – like, were we just allowed to go ahead and make this without some higher up calling the shots? I brushed those feelings off. We were going into uncharted territory here. Feeling a bit uncertain wasn’t indicative of anything other than the fact that we were trying something new, and that was inherently exciting. You might be wondering, around this point, why I haven’t mentioned a director. If so, you’re smarter than I was. Because, in an act of blinkered naivety on my part that I still can’t believe I was stupid enough to allow after years of working in theatre, I figured we didn’t really need one. Yeah. Any guess why we faced challenges early on? I think I was just so carried away by the idea of the whole project, by a brazen sense that we were making something simple, that I didn’t give enough thought to the fact that the series needed a single voice to guide it. I mean, in theory at that point I was that voice – I was editing every script as it came in, taking calls with the actors and handling some of the production stuff, but a showrunner is a different job to director. Which didn’t stop me doing what I felt was enough ‘directing’ to keep the series on track. Before the shoot of episode one I sat in on a read with Rose and Chris, gave them some notes, then logged off to let them film. Piece of cake. John soon came back with two different versions of the first episode. One, shot on the actors’ phones in high definition, felt slow and baggy. The second, using webcams, felt warmer, livelier, but it was by no means a stunning vindication of the whole concept. John and I discussed and agreed version two was preferable, but should we have been shooting in high-def? It was a difficult question without a clear answer. Comparisons to other series that used the same form indicated that we should have been. Love In Lockdown, for example, looks very slick – although to be fair Gristmill has a lot more money than us. But even so, if we wanted to be a contender in the growing field of isolation made entertainment, we had to at least look as professional as possible. In the end, John and I agreed that the high definition version looked too sharp, not at all like an actual video call. For the gritty, downbeat sensibilities of The Pact, filming with standard definition webcams ultimately suited our purposes better. If I’m honest, I still have my doubts about this choice, but it was a choice and in the end the series’ future does not rest on the quality of the footage, but on the quality of the content. On which front we were faced with some problems. I sent the episode around to a few people for feedback and for the most part received muted positivity. It was when I sent it to a friend of mine who works as a filmmaker in a different state, who knew nobody involved except for me, that I finally received a serve of brutal, if kindly phrased, honesty. He liked the story and the concept, but he felt that the episode as it stood just fundamentally did not work. He didn’t believe the performances and didn’t find it especially attention grabbing. Which was going to be a problem if it was supposed to launch a fourteen-part series. It left me at a crossroads. Of course I could choose to ignore him. Nobody else had reacted so negatively. But crucially, nobody else was as unbiased as him. In his reaction I saw the potential reaction of not only the audience we wanted to capture, but the industry at large. I also didn’t want to reshoot. Nobody was getting paid for the project and everybody had already given up a lot of time. There was only so much I could expect of people. But as I watched the episode again and again, the truth became clear. We could not start a series with this. Not one that had any chance of being taken seriously. And that not only meant a reshoot, it meant a rethink of the project across the board. Rose and Chris are two of the best actors I know. But for a story that was becoming increasingly complex and challenging, they couldn’t be expected to fly blind. And while I was cautious of how much I could ask of everyone, I was also aware that to not make the project to the highest standard possible was to do the team a massive disservice, to create a scenario in which the brilliance of the people involved would not be evident. Which would render the whole project pointless. I called John and, tentatively, asked how he would feel about starting episode one from scratch. With the saintly patience that he would demonstrate again and again in the weeks to come, he agreed it was the best option. I apologised for wasting his time, but he simply replied with something that has stuck with me – ‘that’s creativity, man. Trial and error.’ So far what we had made looked a little too much like an error. Which meant a new approach. Namely, that we needed a director and fast.  So, Covid happens and suddenly all the things you would usually do with your time fly out the window. You can’t leave the house and everyone’s on Zoom calls. The internet is full of condescending posts about how productive X was during the Y pandemic of Z year. And while those posts are annoying, they’re at least a break from the endless conspiracy theories, finger wagging and politicising of mask wearing. With the possible exception of the book industry, the arts, at least as a viable form of moneymaking, begin to collapse. You can’t put on plays or make movies. But as the weeks wear on, you find yourself wanting to make something. If only to keep occupied. So what are your options? *** The idea for an isolation web series started with hearing the news that several famous actors were going to make a TV show that was entirely based around video calls, about an agency of agoraphobic detectives. Of course they weren’t the only ones; in Australia we’ve seen the release of shows like Love In Lockdown and Retrograde turn the era of Covid into the contemporaneous setting for brand new comedies, while in the States Parks and Recreation and 30 Rock returned for special, video call based reunions. But what stood out about The Agoraphobics Detective Society was the fact that it isn’t about Covid. Yes, it’s made during quarantine and a product of very specific circumstances, but one that found a different and valid reason to tell its story through video calls than the obvious. Without seeing the show it’s hard to know how well it works, but I liked the fact that it wouldn’t feel dated in a (theoretical) post coronavirus world. So I started thinking and the more I thought the more excited I got. Making a web series with video calls would be easy, right? After all, everyone has a smartphone. Actors could film their parts in isolation, we could edit the footage together and that would be that (that would not be that, but lets not get ahead of ourselves). I decided a mystery would be the most exciting framework for this story, and from there the early pieces fell quickly into place. Six or so episodes, I figured, about a young woman living in Germany whose ex-boyfriend back home in Australia has vanished. Separate from all the people who might know something, her only recourse is to one by one call figures from her shady past in an attempt to shed light on what exactly happened to him – in the process bringing her face to face with the ugly truth behind what made her leave in the first place. The first person I called about the project was Kashmir Sinnamon, a fellow Bitten By Productions member. Tripping over myself, I filled him in on my disparate episode ideas and the writers I wanted to get on board. I asked Kash to assemble his dream cast and we would create characters around them. Next I did something sneaky. I called my good mate John Erasmus, who directed Bitten By’s 2018 horror show Dead Air but also is a very in demand full time editor who has worked on a lot of high-profile projects. I pitched him the idea without ever directly asking if he’d be willing to edit it despite that being exactly what I was hoping for. John, of course, figured it out pretty quickly and luckily mirrored both my enthusiasm and delusion; “should be pretty easy”. In my head, we would get the series written, filmed and edited in about three weeks. Six five-minute episodes – how hard could it be? At this point, unquestionably carried away and wanting nothing more than to dive right in, I wrote a pilot. Morgan, the troubled protagonist, receives a phone call out of nowhere from her estranged half brother Tim. They exchange awkward small talk then Tim reveals his reason for calling; that Morgan’s ex Brett has vanished. He urges Morgan not to look into it, not to ‘dig that shit up again’ but it’s clear that’s not going to happen. For the record, I had no idea when I wrote it where Brett was. I didn’t know why things between Morgan and Tim were so fraught. Or what ‘that shit’ referred to. I had no idea. I wrote it, then I sent it to Kath Atkins and Damian Robb, two writer friends, and asked them what they thought happened next. From there, we started a writer’s room. I sat down with Kath, Damo and ideas were thrown around, including notions of how to proceed. The suggestion was raised that we should set it during Covid, but I was certain the series would work better if it found a different reason to be all through video calls – i.e. the protagonist being overseas and wanting to see the faces of the people she calls to gauge whether they’re lying or not. Plus, thematically, it felt like there was something nice about the video call format, about the characters only showing what suits their agendas. Quickly it became clear that six episodes wouldn’t be enough. As we explored, found answers to our mysteries, and in line with Kash’s suggestions crafted the characters we would need to arrive at those answers, our episode count ballooned to sixteen (later it would go down to fourteen, but it was still way more than John signed up for – sorry man). And while this would naturally mean more work, it also offered the opportunity to bring more people on board. I wanted to keep the story outlining team contained to Kath, Damo and myself in order to ensure we avoided a too many cooks situation, but once the major beats of what had to happen in each episode were worked out, then I wanted to involve as many writers as feasible. After all, half the point of the project was giving creatives something to do. As showrunner, I would be writing the first episode and the finale, but I really wanted episode seven as well, the episode where Morgan comes face to face with her father, who may or may not be responsible for Brett’s disappearance. Damo and Kath were going to write three episodes each, but as we shuffled things around Kath went down to two – although one of those is the climax of the series, and as you’ll know when you see it, the hardest to pull off. For the record, she nailed it. Episode two went to Karl Sarsfield, a recent VCA grad who had acted in a couple of my plays. Episode three to Bonnie McRae, who I work with at Melbourne Young Writer’s Studio and is one of the writers on the still gestating web series version of Heroes. For episode four I recruited Kate Murfett, an old school friend and terrifyingly brilliant writer – her episode would prove to be a particularly special one, but we’ll get to that. Five, six and seven were written by Kath, Damo and myself, while for episode eight John proved that not only is he a magnificent editor, but a fantastic writer as well. Damo wrote nine, and Kashmir, whose recently completed first play Old Gods will hit the stage the moment we’re allowed, wrote the absolutely pivotal episode ten. Eli Landes, who also studied at VCA and works at MYWS, turned what could have been a purely functional episode eleven into a funny, tender and deeply moving calm before the final three-episode storm, written by Kath, Damo and myself. What wowed me the most about the work that every writer – a lot for what ultimately amounts to about eighty minutes of content – did, was how they managed to each bring so much to the series while maintaining a consistent tone and quality. Watching the finished episodes back to back, you can both identify each person’s individual talents, but they never distract from the whole. It feels cohesive, and that to me speaks to what has been my favourite thing about this project; how it was enriched by the many voices involved, all of whom came together to make something unique and singular. Of course, I’ve written this whole post without mentioning two of the most important voices involved in the whole series. But we’ll get to that. After all, this has been a big, complicated, challenging production on a lot of levels, and the relative ease of the early development was not indicative of how things would go the moment filming started. Back during my first year of uni I excitedly took a class called ‘Writing Your Own Life’. At the time I was in the middle of writing a kind of narrative autobiography, something that I can’t quite explain the reasoning behind apart from to say it was a particularly self-indulgent time in my life. Basically, I had happened on the flimsy notion that my teenage years were so fundamentally interesting that I simply had to write them as a novel, a project that at the time I was convinced would be my best and most unique work.

The first glimmers of doubt about the project probably started to creep in during this class. Because while I was very interested in studying what went into writing memoir, the stories that my classmates wrote were uniformly tedious depictions of everyday minutiae with no real drama. And while it took me a little longer to realise that was more or less the case with my own attempt, that class did make me start to consider whether anyone finds our lives as interesting as we do ourselves. While I did eventually end up shelving that project, I don’t regret the time I spent on it. Because what I now have is a fairly detailed account of my teenage years written in very close proximity to them, something I can look back on in the same way you might an old diary. Naturally it’s melodramatic and at times atrociously written, but it’s also more or less an accurate albeit highly subjective recounting of my experiences and from a nostalgic standpoint that’s a nice thing to have. I’m no longer under the illusion that it would have any value to anyone apart from myself, but I’m comfortable with that. The other night, walking back from an old friend’s place after a night of beer and reminiscing, I thought, idly, about the prospect of continuing it. Wouldn’t it be cool, in theory, to have so much of your life documented for yourself in a style designed to be read and enjoyed rather than a dry listing of events? I wasn’t, in the end, seriously considering it. I knew pretty quickly that it wouldn’t happen. Partly it’s a practical thing; to pick up from where I left off would mean covering a decade, and frankly even I don’t think enough of serious interest happened in those years to be worth the time and energy. I also tend to think writers are self-obsessed enough and an undertaking like this one encourages that ugly trait. But ultimately, I think what made me drop the semi-formed idea was the dawning understanding of how redundant it would actually be. Because in many ways I have chronicled the last few years of my life. Not in the same way, chronologically and without embellishment, but I have written plays, short stories and even a six-part TV show draft that to varying degrees take real events and turn them into narratives. It’s a spectrum of course. Something like Three Eulogies For Tyson Miller is an essentially accurate depiction of a real friendship albeit with the names changed and an altered outcome. We Are Adults, the aforementioned TV thing, is basically a remix of events from my early twenties in the guise of a kooky comedy (I know that every young male screenwriter under the sun has tried to write something like this, leave me alone). Plays like Regression or The Critic take particular emotions or experiences that are absolutely rooted in reality and explore them through the prism of made up characters or scenarios. Nothing I’ve done since that autobiographical project has been quite as pure in terms of truthfulness, but these other works have essentially continued the essence. Because to write is to be in conversation with your own life, to examine the things you’ve been through and find new perspectives on them through proxy characters, to try and make the personal and painful interesting to an external audience. It’s exactly why that ‘Writing Your Own Life’ class was so appealing to so many people. But the truth is, unless you’ve had a really unique one your life is rarely all that different from anyone else’s. We all have our demons, our regrets and our lessons learned and writers in particular tend to want to share and examine them. But the answer is seldom through direct autobiography. Because the truth, weirdly, can be constraining. When Nelson and the Gallagher sold to HarperCollins, my publisher asked two questions. The first was whether the book was autobiographical. Yeah, I admitted. While it’s heavily embellished the basic setting and events of the narrative were lifted from a particular time in my life. The second question cut to the core of the book in a way that I had not yet managed. ‘Are the things the main character learns in this book the things you wished you had learned earlier?’ I was floored. Because I hadn’t thought about it and suddenly it made the whole book that much clearer. I had used real events but in building a fictional narrative around them I was given the freedom to allow my self-based protagonist to discover the things it took me years to. Which, in a weird way, makes Nelson and the Gallagher a truer work of self-expression that a verbatim retelling of the actual events could ever be. Because the significance of an experience is never really clear in the moment. In fiction, however, it can be. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

October 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed