The opening of Springsteen last week officially marked the tenth play of my theatre company, Bitten By Productions. In some ways it’s a milestone; ten plays in roughly three and a half years feels like a lot considering we’re a tiny, no budget indie company but the fact is, I write fast and we produce cheap. But lately I’ve been starting to feel like we’ve probably done as much as we can in the no-budget sphere of theatre we’re operating in. We’ve been on a bit of a hot streak of good reviews and decent audiences lately, but after the pains of watching Springsteen performed in a venue that has, charitably put, presented significant challenges, I’ve made a promise to myself that from now on we need to be presenting the plays in a way that suits the calibre we’re now operating at. The brilliant casts we seem lucky enough to assemble for each show deserve better.

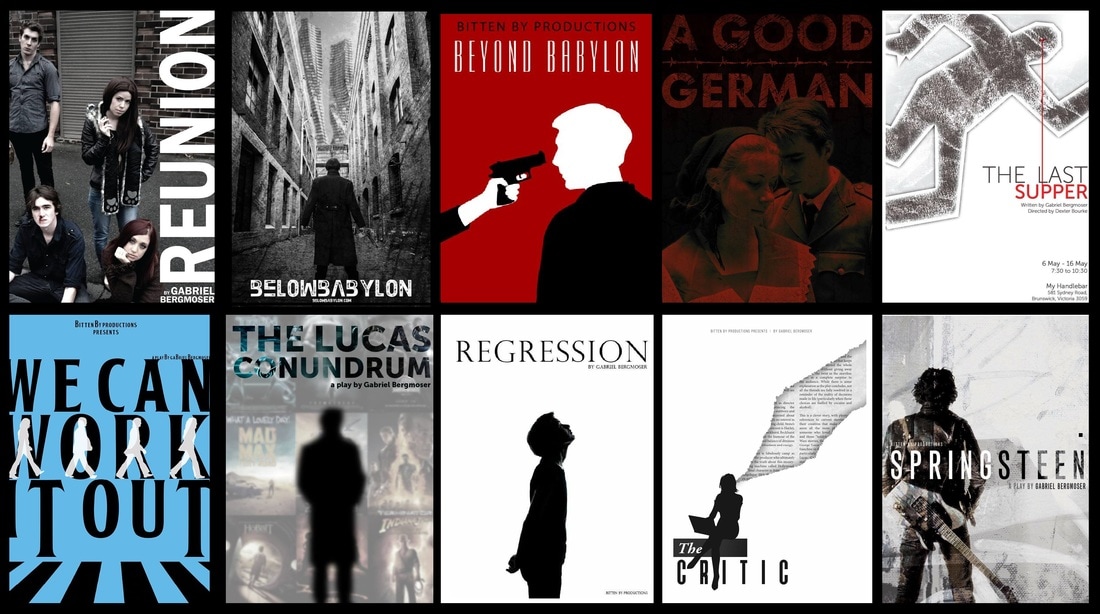

The odd thing is that we started off operating at a higher production standard than we do now. A couple of our early shows had a relatively high amount of money sunk into them and had actual sets and costumes, with the sparser, more minimalist shows intended to be the exception rather than the rule. But reality got in the way and while I don’t think many of our recent shows have needed a much more elaborate presentation, thinking about the future makes it pretty clear that we need to change the way we operate, and after this, our tenth play, the time is ripe. But thinking about the future often has the strange effect of making you think about the past and ten plays in I wanted to do a bit of a retrospective of our output to date; for my money, what worked, what didn’t work, what I’m proud of and what makes me want to bash my head against a brick wall. Reunion Reunion was one of our least ambitious plays in every way, but it was never meant to be more than what it was. Presented at the Butterfly Club in Melbourne with a set consisting of a table and four chairs, a cast of five and a running time just on an hour, Reunion told the story of four high school friends who get together for a drink five years after the last time they all saw each other and things, of course, go terribly wrong. When our shows are discussed over beers at the pub Reunion always tends to get a bit ignored. Personally though, I will always have a real soft spot for this show. It was sentimental, a little corny and a very ramshackle, skin-of-our-teeth production but it was also the first time I had written, directed and produced my own play and it was a very personal story. I will always remember the moment after closing night when I walked out on to the empty stage and thought ‘shit, we actually pulled this off’. Reunion was far from perfect or memorable, but it represented a starting point and for that I remember it very fondly. Below Babylon When we started Reunion we weren’t yet Bitten By Productions; it was only during that process that we decided to start a company and Reunion sort of retroactively became our first production about halfway through the rehearsal process. But our first real team effort was Below Babylon, a futuristic thriller about a former assassin preparing for a final showdown with his nemesis. Below Babylon was a passion project for everyone involved from start to finish and part of me still suspects that the only reason anyone agreed to do Reunion was because it promised them a part of Below Babylon. In terms of production, we’ve never since gone all out in the way we did with Below Babylon. We had a website designed from the ground up, we had a pretty feeble attempt at a viral marketing campaign (covering the city in posters saying ‘WHAT IS BELOW BABYLON?’ with a link to the website) and we even had a tie-in prequel comic. Lots of money was spent on an awesome set and props; visually we’ve never again matched that level. Below Babylon showed every cent that was poured into it. The problem was the script. I’ll always be grateful for everyone having the faith in my work that they did, but Below Babylon promised an edgy noir thriller and in reality it’s kind of boring. Most of the first half is just exposition and while I was starting to develop the style of bouncy dialogue I predominantly use now, I went for a pretty weak attempt at hardboiled western/noir dialogue that just made everyone sound slightly constipated. However, I am still extremely proud of the final scene of the play, when the long-promised showdown occurs in bloody, spectacular and twisted fashion. In a lot of ways the whole play was just treading water until I could get to that scene and even now in retrospect it’s killer; one of the first times I could tell from sitting in an audience just how much I had everyone on the edge of their seats. But the rest of Below Babylon was just too bloated and humourless to really deserve all the money and work poured into it. Everybody was operating at their A-game, but in this case it was me who let the team down. Beyond Babylon Beyond Babylon started life as a bit of a side project, a semi-sequel to Below written during the rehearsal process and featuring one of the surviving characters in a new story set in the same world, but from the start it was designed to be a different beast. A two hander, Beyond Babylon was the cheaper, nastier cousin to the first play, and while it didn’t have the visuals to match its predecessor, it was better in just about every other way. Just about. Beyond suffered from something I’ve always grappled with in that it is just way too talky at the expense of very much happening. More recently I reunited with the cast of two to rework the show for a festival and we quite easily reduced it from an hour to fifteen minutes without losing anything essential. Beyond had significantly better dialogue that Below, had a better ending and more compelling themes but ultimately it was a short play bloated to full length and as such was kind of draggy and repetitive. That said, Dhania and Finn both gave brilliant performances and Beyond was our first play that got unequivocally good reviews. It was also the first time I started to really get a handle on directing. Ultimately it was a very rewarding show, albeit a flawed one. A Good German Yeah. Okay. This one. Chances are some people have clicked on this wanting to see what I have to say about A Good German. The answer is a lot, but I’ll try to be succinct. A Good German is tough because it’s the only show of ours I outright regret and look back on with embarrassment, but it was the most valuable learning curve I’ve ever experienced. Straight up; A Good German is the worst script I’ve ever written, only matched by the worst production we’ve yet done. Not the worst because it was cheap or anything; it’s the only play since Below Babylon that tried anything remotely ambitious for set or costumes, but the problem is you get very few points for trying if a play is about the Holocaust and you don’t succeed. Here’s the thing; three reasonably successful shows in, we got arrogant. A Good German was an idea I’d had since high school, about a Nazi soldier who becomes infatuated with a Jewish inmate in a concentration camp. The script went through multiple drafts, none of which I was happy with, but in the end I listened when people told me it was good even though I suspected it wasn’t and let the show go ahead with an attitude of ‘she’ll be right’. She was not right. She was not right at all. We made so many mistakes that seemed so obvious in hindsight. We let the play go forward in the hands of a director who had never directed before. I stupidly decided to audition despite the fact that I had long since stopped acting and my stupid decision was only matched by the stupider decision of the directors to cast me in the lead role. Only a couple of the cast could really do a German accent (I was not one of them) and instead of making a call to get rid of the accents, what we ended up with was a strange collection of vocal Frankensteins, which didn’t help when the dialogue already made Below Babylon look like Shakespeare. The rehearsal process was rushed; we had a month from auditions to opening. The costumes either didn’t fit properly or didn’t make sense (all the Jewish inmates wore nice, clean clothes). Did I mention this play was about the Holocaust? There were circumstances beyond our control; the Revolt, where we had previously done Below Babylon, had since undergone a change in management, by which I mean there no longer was any management, and so our set was only bumped in the day before opening night. Additionally, a few of the shows happened to fall on the same night as a dance concert next door that nobody saw fit to tell us about, meaning depictions of some of history’s greatest atrocities were regularly punctuated with bursts of Beyonce. But ultimately, had we been more organised, none of this would have been a problem. Had we been more organised, we would not have done this play, or would have done more rigorous workshopping or redrafting. But we did none of those things and were rightly eviscerated for it by our first review. I so vividly remember the morning after opening night, waking up to read what remains to this day the most savage review of anything I’ve ever read. I remember the sinking feeling in my stomach and the whole ensuing day of telling myself and anybody who would listen that I didn’t care, that the guy just didn’t get the play but knowing on some level that he was right, that we had fucked up and had to wear it, that we were asking an audience to come and pay for something that was not only an embarrassment, but actively offensive in its apparently cavalier attitude to the Holocaust. All I can say is that we didn’t set out to seem like we didn’t care. We did care. We just got cocky and we assumed it would all be okay. And if there’s one thing I’ve learned about theatre, it’s that that is never the case. If you put on a play, you’d better be sure that you believe in it a hundred percent. I didn’t, and that means that the responsibility for A Good German will always rest with me. The Last Supper So, coming off a creative failure on the level of A Good German, what’s a fledgling production company to do? Basically, learn and change. So when the time came to do The Last Supper, the third part of an accidental trilogy with Below Babylon and Beyond Babylon, we approached everything differently. Luckily the script, which I had written in a giddy three day writing session, was probably the best thing I had written up until that point; not perfect, but a damn sight better than what had come before it, so we were working off a stronger foundation than ever before. We brought in an experienced director. We made the play profit share, meaning that the cast we attracted were of a higher calibre due to the very effective promise of some payment. And for once, things went pretty smoothly. There were two major issues with The Last Supper. One, despite containing moments that I think rank as some of my best, the script did have its issues. Far too much of it was devoted to recapping or discussing the previous two plays, so The Last Supper doesn’t really kick into gear until roughly its halfway point. And two, which seems to still be a theme for us, the venue. I don’t want to get into the many, many issues we had at My Handlebar in Brunswick, the since closed bar that you may have heard of due to an unfortunate run in with one Clementine Ford, but suffice to say that despite having built a theatre upstairs, the place had no interest in actually running one, meaning that the play was constantly punctuated by beeping and yelling from outside (soundproofing was not a concern) and, even worse, loud music from the bar downstairs that apparently simply could not be turned down. Still, we powered through. The Last Supper represented a turning point for us and set us up for better shows to come. We Can Work It Out I still think to this day that We Can Work It Out is our best play yet. An hour long comedy about the Beatles, We Can Work It Out was the first script written after doing my Masters of Screenwriting at VCA and it shows. Structurally it’s impeccable. It’s also very funny, thematically on point and has buckets of heart. We assembled a great cast and the tiny venue Voltaire actually worked in its favour, giving it an intimate, quirky feel. We Can Work It Out opened to full house shows, rapturous audiences and glowing reviews. It’s not my favourite of my scripts, but this was the first time that almost everything came together in the right way. Consequently, it only gets one paragraph. The Lucas Conundrum Still buzzing after We Can Work It Out we went straight into The Lucas Conundrum, a black comedy about a Hollywood director trying to avoid letting a dying kid see his latest blockbuster before its ready. Also performed at Voltaire, The Lucas Conundrum had a great cast, a top director in Ash Tardy and also had a great reception. Lots of laughs, good reviews, plus it remains my parents’ favourite of all my plays. Script-wise it had issues; it drags in the middle and gets a little too didactic at times, but I think it made up for it with a great twists and an oddly sweet ending that made it more than just a snarky look at Hollywood. Regression I get bored easily, and so after two well received shows mostly centred around four people in a room having debates about art, it seemed time to shake things up. And when it came to Regression, a play I probably consider to be my best, a different presentation seemed like a good idea. When my high school drama teacher Joachim Matschoss, who is regularly in production on shows all around the world, expressed interest in directing it I took the opportunity. Joachim is a highly stylistic, non-naturalistic, visual director. My plays are fairly grounded and dialogue driven. I suspected this combination would result in something very different and special and for the most part I think it did. Performed in the studio space at Allpress Espresso, Regression was unlike anything we’d done before. Performed in the round with the actors interacting both behind and in front of the audience, Regression was strange, atmospheric and eerie, utilising an unconventional space to tell an unconventional story. I wasn’t 100% thrilled though. I gave Joachim full creative freedom and so he tweaked the script slightly to fit his vision, which I was okay with, but there are moments I wish he hadn’t cut, chief among them the ending. I don’t want to be that writer who complains about every word not being used, but I did feel a bit confused that moments I was really proud of in the script were replaced with what I felt to be unnecessary improvisation. All that said, it was exciting, new and different for us, and the reviews reflected that. And, in a little moment of personal vindication, it got a glowing write up from the same guy who eviscerated A Good German two years previously. So that was alright. The Critic On the script level, I didn’t think much of The Critic. It wasn’t especially deep or personal, more of a comedic look at the odd relationship between creatives and critics, based on my experiences as both. I liked what I had written, but it didn’t feel like it was hitting the same heights as something like Regression. To me it rounded out a little thematic trilogy with We Can Work it Out and The Lucas Conundrum, so appropriately it was also performed at Club Voltaire. And like those two plays, it did very bloody well. Better than very bloody well. In the endlessly capable hands of Ash and with a top notch cast of four brilliant women, The Critic got us our best reviews ever, including my first and to date only five star review. I think this play was just a perfect marriage of all the things we have started to do very well; with no money behind us, we have to rely on good scripts, good direction and good acting to make our shows worthwhile, and I do feel like we’re at a point where we’re consistently operating on that level. The Critic wasn’t ambitious, but it was very good, and that’s probably more important. Springsteen How do you write semi-objectively about a play that’s halfway through its run? You can’t, so instead I will write with gushing subjectivity, with enthusiasm carried over from a first week that has exceeded all expectations. I honestly didn’t know how Springsteen would be received. Would the Bruce buffs hate it due to its less-than-flattering portrayal of the central character? Would it fly over the heads of Springsteen newbies? Would people find it boring due to a lack of explosive twists or broad humour? Apparently none of the above. Springsteen has been received with the kind of enthusiasm I haven’t seen since We Can Work It Out (funny that). We’ve had people return for multiple viewings, we’ve had reports of tears from people who know nothing about Bruce and we’ve had hardcore fans demanding photos with Chris, the actor playing the icon. Next week is almost completely sold out and the reviews have been excellent. So much of that is down to the cast we have assembled, probably across the board the best I’ve ever worked with. As a director, Springsteen has been by far the most rewarding thing I’ve done. Stressful and terrifying, but it seems to have paid off. Next? Okay so this was predictably lengthy, and if you’ve read the whole thing hats off to you. I assume anyone who clicks on this probably was involved in one of our shows and skipped to the bit they were in to see if they were mentioned, which is fair enough although I tried to steer clear of naming names. Writing this was more for me, a way to articulate my thoughts as we come into the next chapter of our company’s life. Our immediate next show is Dracula: Last Voyage of the Demeter, the first Bitten By Production not written by me, which means a bit of a break. Then it’ll either be Heroes or Chris Hawkins, a pair of dark thrillers I wrote last year, or Moonlite, a musical I’ve been working on with a good friend about the life of a (real) gay bushranger. Beyond that we have The Commune, another thriller and our first co-production with a different company. Basically, the future looks bright for us. I’m trying to look at everything we’ve done before as honestly as I can to see what worked and what didn’t work, but I really do believe we’re in a good place right now. We’ve got all the right people on board and after some big mistakes I think we’re more clearheaded in how we approach things. The early days were marked by a lot of clashes of egos and unpleasant politics, but we’re past that now and I think we have the right attitude about what needs to happen for us to continue to grow, develop and innovate. In short, it’s gonna be a good year.

1 Comment

It wouldn’t be an enormous stretch to say that A Series of Unfortunate Events is my favourite children’s series of all time, and so the announcement that Netflix was going to be adapting it into a TV series was just about one of the most exciting things that ever happened, rivalled only by when I received screeners for the first four episodes. These arrived rather unexpectedly, so I hadn’t yet had the chance to re-read the first four books that the Netflix series is adapting. Luckily the episodes I had received only covered the first two books, so I swiftly set to work reading The Bad Beginning and The Reptile Room before giddily diving into the screeners.

The Netflix series, for the record, is excellent and an absolute gift to people who love the books as much as I do, but this isn’t about the show. I want to talk about the experience of reading those books as an adult. I had only planned to revisit the first two and then read the next two before the official release, but that wasn’t what happened. Within minutes of finishing The Reptile Room I was on to The Wide Window and suddenly buried in a devoted binge-read of the whole series, going through a book a day even as they got thicker and denser. It was a strange, dizzying experience where I maybe wasn’t paying as much attention as I could have due to the fast-paced nature of the read but was so lost in the world, lore, story and characters that it didn’t really matter as one book blurred into the next and the story of the Baudelaire orphans unfolded like one long, tangled, winding novel. Due to signing an embargo that means I can’t publicly refer to having seen the show until January 5, I won’t be posting until then, but I’m writing this literally minutes after putting down The End, while the storm of emotions I experienced over the last couple of weeks is all still fresh in my head. Nostalgia is a big one, of course, as is always a part of revisiting any series that you grew up loving. I found myself flashing back to all the places I was when I eagerly dived into each new book upon release and the excitement of thinking that maybe this time all my questions would be answered, before Daniel Handler piled on a whole new assortment of mysteries on top of the ones that remained frustratingly unsolved. I relived the obsession I had with all things V.F.D, Snicket, Olaf and Baudelaire, combing the books for clues and hints that, in retrospect, seem far less meticulously planned than I chose to believe they were when I was younger. But nostalgia is ultimately a shallow reason to enjoy something, and to me the definition of a classic is how it holds up to multiple readings/viewings. And while the early books in the series were well worn from how many times I read them as a kid, the later books weren’t nearly as ingrained in my memory due to only having read them once. The possibility lingered that the series might not be as good as I remembered it, and while I was reasonably confident that wouldn’t be the case, part of me was a little concerned that I would be tainting my lingering love for the books by viewing them with adult eyes. Luckily, that wasn’t the case. And while the early books are fairly repetitive and predictable, all following more or less the same formula, they’re short enough that it doesn’t really matter and once you reach the second half of the series the wild ride really begins. And so does the realisation that, while I always suspected there were hidden depths to this series, I was too young during my initial discovery of them to really appreciate what Daniel Handler was trying to do. A Series of Unfortunate Events isn’t perfect, but no masterpiece is. Flaws tend to give something its individuality, and besides, the thematic genius of this series far outweighs any plotting/pacing/believability issues. As a kid I think I struggled to get my head around the tone of the series; absurd and blackly comedic one second, sombre and meditative the next. As an adult though, it makes a lot more sense and is a lot more rewarding. A Series of Unfortunate Events starts out as a dark joke; watch bad things happen to unfailingly good people. By the end it’s so much more than that. It’s a celebration of curiosity, literacy and decency. It’s a rallying call for the best in humanity. It’s a searing indictment of talking down to children or trying to shelter them from the things that we don’t believe they can understand. It’s a gentle assurance that even though someone might be flawed, it doesn’t mean they’re a bad person. And it wraps all of that up in an intoxicating cocktail of gripping storytelling, shocking twists, compelling mysteries, witty wordplay and lots and lots of outright hilarity. I think the biggest telling point for how this series shifts on a second read from a more grown up perspective is how I felt about the conclusion. As a kid, The End was frustrating and anticlimactic; after the brilliance of The Penultimate Peril, which brought together all the plot threads of the preceding novels but stopped short of answering any massive questions, The End felt like it should have provided the solutions to all the lingering mysteries. Did the Baudelaire parents have anything to do with the death of Olaf’s? What really happened between Lemony Snicket and Beatrice? Do the Quagmires survive? Is Aunt Josephine alive and was she the woman who lured Widdershins away from the Queequeg at the worst possible moment? What exactly is V.F.D? And just what is the importance of the Sugar Bowl? Some of these questions are answered in the excellent prequel series All The Wrong Questions (which I’m starting a re-read of tomorrow) but The End provides just about no closure for any of them, which is hugely annoying when you’re a fourteen year old who’s spent far too much time counting down the days until all these tantalising mysteries are solved. But coming into The End knowing this allows the book to reveal itself as what it actually is; essentially a thesis for all the central themes of the series, themes that made it far more than its secrets. The End basically forgets all the lingering loose ends regarding V.F.D and instead takes Olaf and the Baudelaires to a distant island overseen by Ishmael, a dictator who attempts to shelter his people from anything upsetting. Items that might be useful are discarded, books that might be revelatory are hidden and the people of the island are kept dosed up with an opiate that stops them getting too restless with their tedious circumstances. The arrival of the Baudelaires and their nemesis changes things, however, and in a key scene the children learn that their parents were here before them but kept silent about the whole experience. Ishmael makes a compelling case for their parents attempting to protect them from secrets better left unsolved, in much the same way as he protects the people on the island from the darkness and complexity of the outside world. The Baudelaires are given a choice; is it better to live safely without considering any dangerous ideas or confronting anything ominous, or is it better to ask questions, live your life, experience the world and accept that doing so means you will sooner or later come up against evil and injustice? Handler squarely comes down on the side of the latter, because, as the people of the island learn, you can’t hide from the things that scare you forever. The world is not a safe or gentle place, and the sooner you realise that the better. Handler famously detests condescending children’s stories with contrived happy endings because that’s not how life works, and to pretend otherwise for the sake of sparing people some discomfort is to lie. I think it’s this central ethos that makes Unfortunate Events special, that makes it so much more than just a lot of dark humour and frustrating McGuffins. Like any classic, the things that draw people to it, while fantastic in their own right, are in many ways just window dressing for the deeper purpose below it all. Is The End satisfying from a plot perspective? Not especially, but thematically it’s about the most perfect conclusion this series could ask for. But finding a deeper appreciation for the themes of the story doesn’t in any way dilute everything else. A Series of Unfortunate Events is as funny and resolutely odd as ever, and I found myself analysing all the mysteries all over again and tweeting my theories to the three people who might know what I’m on about. Having read All The Wrong Questions gave me some new ideas about all those lingering loose ends, and I’m looking forward to seeing if the more recent series is just as good on the second go round as its predecessor. But as far as A Series of Unfortunate Events is concerned, for my money it is a masterpiece of children’s literature, unlike anything that came before or after it. It’s not every bit as good as I remembered; it’s much, much better. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed