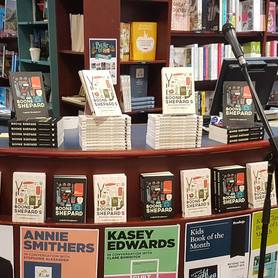

It’s been a big week for a certain Mr Shepard. Monday marked the release of Boone Shepard’s American Adventure, my second published novel and second in the series, and the very next day saw the announcement that the first book has been shortlisted for the Readings Young Adult Prize. So yeah, it’s safe to say that things feel pretty great right about now. Anyone who knows me knows how long Boone Shepard has been around; from a weird novella I wrote in 2008 to binge writing the first drafts of four books over the course of 2014, to the publication of the first book last year and now the second, he’s never really gone away. He exists as a strange anomaly among the rest of my writing; not as comedic or dark as many of my plays, or as twisted and Machiavellian as something like Windmills, and yet, while there’s very little else in my body of work that is similar to Boone, his story is probably my favourite. Seeing two books side by side last night in a bookstore I’ve loved since I was a kid, and seeing him side by side on a shortlist with books published by the heavy hitters is surreal. When I was a teenager nobody thought this idea was worthwhile. Before it was published, most of my friends had zero interest in reading about him. And yet, stubbornly, Boone refused to go away and bit by bit people are noticing. Last year’s launch was wonderful, but I think I felt a bit overwhelmed by everything. Last night was much more relaxed; we still had a great turn out, but separated from the stress of it being the first time I think I just felt like I could enjoy myself more. It was one of those nights that just leaves you feeling content, and the announcement of the shortlist consolidated that. Things have never looked better for Boone, and to boot I’m extremely proud of American Adventure. That’s not to say that I wasn’t proud of the first one, but much like the difference in the two launches I think there was less pressure on the second book, and with the world and characters established it was easier to just have fun with it. I’ve written at length before about the long, tangled process it took to get American Adventure right, but re-reading it in published form the other day really brought home how much I feel like I got this one right, like it’s every bit as funny, action packed, and heartfelt as I wanted it to be. Of course, my opinion is just slightly biased, but you don’t always feel like you actually achieved what you set out to with a piece of writing, and in the case of American Adventure I think the many drafts and endless reworkings really paid off. So what now? Well, thinking about books 3 and 4 is probably premature, but that’s what I’m doing. Plus ongoing discussions linger in the background about potential TV, stage and phone game adaptations, so it’s not like there’s ever any respite from the Boone Shepard business, a business that is starting to feel more worthwhile than ever before. For now though, I think I’m going to give myself a few days to relax, enjoy the moment, and hope that people like American Adventure. But as always, the next adventure is just around the corner, and part of me can’t wait to get cracking. Actually who am I kidding. All of me can’t wait to get cracking.

0 Comments

The immense power of Dr Hannibal Lecter as a character is pretty much accepted by now. Even accusations of his menace having been diluted by overexposure were swiftly put to rest by the impact of Mads Mikkelsen’s recent interpretation over three seasons of the TV series Hannibal, proving that all an icon needs to regain relevance is a fresh perspective, albeit one that understands the fundamentals of what made the icon iconic in the first place. In the case of Hannibal Lecter, much of his power comes from what, in a different light, might be considered his greatest flaw; as a character he just doesn’t make a ton of sense. He’s neither sociopath nor psychopath; he’s capable of love, mercy and compassion, of acts of sickening violence and pointless cruelty. He can be erudite and charming one moment, crass and uncouth the next. He detests rudeness and yet has no issue treating people he considers his intellectual inferiors like dirt. He loves animals yet is believed to have exhibited torturing them as the first sign of his psychosis, he claims to have always been the way he is yet was ostensibly formed by the trauma he experienced in the Second World War. The thing is, this inconsistency is part of the character’s allure. In the first two books by Thomas Harris, Hannibal Lecter was always slightly unknowable, always a distant, string pulling figure, never one to be examined or analysed in any way that might damage his mystique. The latter novels in the series, Hannibal and Hannibal Rising were arguably responsible for diluting his evil by trying to explain it, before the TV series reinterpreted this backstory as just one of many lies he told for his own amusement. The television series spends a lot of time strongly underlining the notion that Hannibal Lecter is in many ways a Lucifer figure, a fallen angel who loves and detests mankind at once, pushing them to their limits and seeing what happens, constantly taunting God in his corruption of Creation. At first blush, this seems like a bit of fun, if not especially meaningful subtext, comparable to all the Judas Iscariot image that Harris threads around the character of Rinaldo Pazzi in the novel Hannibal; a cool parallel, but not especially meaningful. However what if we were to assume for a moment here that subtext is in fact text, that Hannibal Lecter is supposed to represent Lucifer? It would explain a few things. The lack of psychological realism, the otherworldliness, the contradictions and the infallibility of all his designs. He is impossible to defeat because he is literally a deity among men, one who only ever seems like you have him on the ropes when he is in fact always exactly where he wants to be. Of course, the notion verges on absurd. Biblical subtext almost always lends power, whether earned or unearned, but that doesn’t mean there is any actual significance to it, especially not in a series of somewhat pulpy crime novels. Unless there is. So if we decide to play this game, what does it actually mean? Immediately, the character of Francis Dolarhyde takes on a whole new significance. Consider the title of the novel, and the primary motivation of the killer. Dolarhyde is hellbent on becoming the Great Red Dragon as depicted in the Blake painting, a figure of monstrous power and unimaginable evil that will eradicate his perceived weaknesses. But of course, the role of the Great Red Dragon in this universe has already been taken, as Blake’s image of the dragon was very simply an image of Satan. Dolarhyde feels drawn to Lecter; basically the murderous equivalent of a sycophantic fanboy. Lecter, for his part, is amused by Dolarhyde and sees his use insofar as he can help with his ongoing project, being the corruption (in the TV series) or destruction (in the novel) of Will Graham. But Lecter doesn’t see Dolarhyde as his equal or even as especially interesting. Dolarhyde is quite literally a wannabe, with Lecter as the goal he aspires to, something that makes a lot more sense if we are to assume that Lecter in this universe is representative of Satan. Seen in this light, Red Dragon, essentially the story of three men pulled into each other’s orbit, becomes a fascinating story of man’s relationship with the devil. On the one had you have Will Graham, the man with the capability for darkness running away from it, on the other you have Dolarhyde, the man who so desperately wants to be an evil incarnate and yet is hamstrung by his own stubborn humanity, and between them both you have the devil himself using one to break the other one. In some ways it’s almost a Garden of Eden parable only with a little more serial murder and manipulation; Will Graham is Eve, Lecter the snake and Dolarhyde the apple. Dolarhyde is pushed by Lecter closer and closer to Will, forcing Graham to accept the offer, kill the monster and in the process come closer to what Lecter believes to be his true self. The biblical parallels are a lot stronger in the TV series than the novel; in the book Lecter quite simply wants Will Graham dead and his taunting about their similarities is more part of an ongoing effort to break the FBI agent than any attempt at twisted connection. In fact, the more symbolic significance of the Red Dragon story only really becomes clear in the light of its two sequels. The novel and film Hannibal both come in for a lot of criticism; in both mediums seen as an inferior follow up to the genre defining The Silence of the Lambs, but the truth is that in Harris’ vision at least Silence is incomplete without its successor. To really understand the story of Hannibal Lecter and Clarice Starling we have to look at both books together, to look at how and why their relationship starts and the way that it ends. In Silence Clarice is sent by Jack Crawford to interview Lecter in pursuit of potential insight into the ongoing case of Buffalo Bill (note that in the novel this killer doesn’t get nearly the amount of character development or humanisation as Dolarhyde, a fact that has its own significance). The big warning Crawford gives Clarice is to not allow Lecter inside her head. But Clarice, upon realising that Lecter knows more about the murders than he is letting on and understanding that he responds to her courtesy more than the condescension or cruelty of his captors, makes a very literal deal with the devil; she will give Lecter personal information about herself in exchange for information about the case. She offers her soul to Lecter in order to save Catherine Martin, forging a terrible connection to the killer. Seen in this light, Hannibal the novel becomes the second part of a Faustian tragedy; because in every story about making a deal with the devil the bill always comes due. At the end of the novel Clarice’s association with Hannibal and conflict with the corrupt FBI out to destroy him end up eradicating the things that made her her. Clarice’s sense of justice is swept away as Hannibal brainwashes and manipulates her into becoming his lover. Of course there is an argument to be made here that Hannibal’s intention was recreating his dead sister and Clarice’s sheer force of personality was what prevented this, but the Clarice Starling who meets the discovery of an injustice with the phrase ‘the world will not be this way within the reach of my arm’ is not about to willingly run off with a monstrous serial killer. Clarice Starling was never like Will Graham. She never carried that same potential for darkness. She might retain some of her identity at the end of the novel but it will always be compromised. She offered herself to Hannibal in exchange for the defeat of Buffalo Bill, and in the end Hannibal took what was his. There are aspects of that conclusion that may seem almost romantic, but of course that’s the thing about the devil; temptation is a key part of corruption. Hannibal Lecter has taken away Clarice Starling’s sense of self, the one thing that defined her as a person, and for this reason the often-misinterpreted ending of the novel Hannibal will always be the conclusion of a true tragedy. Yes, conclusion, because for this interpretation to work there really isn’t any room for Hannibal Rising. But, of course, Hannibal Rising does exist and explicitly undermines the idea of Hannibal Lecter as an unknowable elemental force. It removes the inability to explain him by trying to explain him and in the process weakens the character. And by way of its own existence, Rising makes one attempt at understanding the character slip through our fingers, because who are we to dispute the ideas and vision of the character’s own creator? Once again Lecter contradicts himself and once again we are left struggling to understand. But see, that is why Hannibal Lecter will never die, will never cease to fascinate, terrify and inspire us. That is why the TV series got such a fervent following and The Silence of the Lambs staked a claim as one of the greatest films ever made. Because, as someone a lot smarter than me once said, a classic is a story that never finishes saying what it has to say. The true genius of the Hannibal Lecter character and the stories he inhabits is not in the subtext of what he might represent, but in the fact that there are so many interpretations that are all valid, interpretations that manage to disappear like smoke when examined too closely. Every time we watch or read his story, in whatever version we might favour, we can see something new. And with that element wrapped up in what is above all a cracking good story, it’s hard to ask for much more from any work of fiction. So yeah. Hannibal is the best. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed