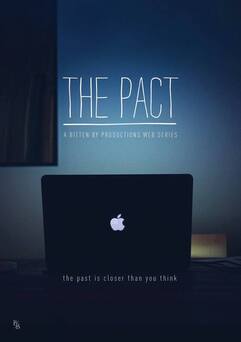

It’s odd to look back now and think that the lifting of Covid restrictions was looking to be a problem for us. Obviously not a massive one –the timeliness of your web series potentially dissipating due to an improvement in state-wide circumstances is such an absurd first world problem that it can’t even fairly be called a first world problem. Nonetheless, it was a factor; The Pact was designed to be an example of the good work that could be made even in trying circumstances. The series not being set during the pandemic would certainly help it maintain a degree of timelessness, but it wouldn’t have the same impact once the lockdown was well and truly over. And with seven episodes filmed and seven more to go, restrictions were lifting at a speed that made us think we had to pick up the pace or be relegated a relic of a time everyone wanted to forget. What sweet summer children we were. It was Pete who suggested cheating. Yes, part of the sales pitch of The Pact was that it was written, rehearsed, filmed and edited entirely remotely, but if more than five people could be in a room then maybe there was an opportunity for us to increase the pace of shooting without sacrificing the quality. So Pete called with a pitch; a big, all-day, in-person rehearsal. We’d get together the cast members with remaining episodes to shoot, read through the scripts, then collectively workshop and rehearse everything left. Pete’s reasoning was that, without the barrier of a screen between the actors and director, more could be done in a shorter span of time. Then, striking while the iron was hot, the remainder of the series would be filmed over the following week; one or two episodes a day, wrapping the whole thing in less time than it had on average taken us to get one episode done. It was an ambitious plan, one which had my complete support. Patience has never been a virtue of mine, and if I’m honest the slow pace of production until that point had been a little frustrating. After all, the series was intended as something that could be turned around fast, but then it was also intended to include only six episodes and be made without a director, so my total lack of realistic forethought was pretty well established by that point. The date was locked in and we pulled together as much of the team as we could. Laila Thaker and Enzo Nazario had already shot their episodes, so they weren’t present, while Michelle Robertson was yet to shoot hers but wasn’t available. Rose, of course, was there – meeting Pete in person for the first time after many hours of filming and rehearsing together. Chris Farrell, who still had one episode to shoot as Morgan’s brother Tim, was there, along with Greg Caine – who had already shot his first episode as Morgan’s conniving father Jack Carlin but had one yet to go. Otherwise we were joined by Justin Anderson, recently cast as the duplicitous Uncle Gary, Tatiana Kotsimbos, who plays the key role of Jade, and of course John and Kashmir, who had been helping to guide the project from the start. The one cast member with material yet to film who couldn’t be there was James Biasetto, who lives in Sydney and as such had a pretty decent excuse. It was the first time the majority of The Pact team had been together in a room and, like Pete and Rose, the first time several of those people had met in person. There was a definite sense of excitement as we settled in for the table read that would kick off the day, starting from episode six. Seven had already been shot, but Pete felt it would help to hear it anyway, just to aid the flow of the narrative. So Rose and Greg, with the dialogue still fresh in their heads, got to it. And just… holy shit. Episode seven was an important one for me. As the episode where Morgan faces off with her father and in the process starts to understand just what she’s up against, it’s the midpoint of the series and several writers had expressed interest in taking it on. But I’d clung to it for a couple of reasons; partly because Jack Carlin is a character who has appeared in other works of mine and I strongly felt that I needed to at least write his introduction to The Pact, but also because when you’re doing the showrunner job that I was, there isn’t a huge amount of opportunity to really write. Let me explain just a little bit. Episodes one and fourteen were the hardest to crack because of all the heavy lifting they had to do. One of the major reasons we re-shot episode one several times is because it had to establish Morgan as a character, introduce the mysteries, set up the themes of the series and do all of this while making an audience invested enough to watch the next episode. It was, not to put too fine a point on it, fucking hard. The same went for fourteen, which had to resolve everything in a satisfying way, make sure the final puzzle pieces of our mystery fit neatly without any egregious dangling questions, and still be an engaging piece of drama in its own right. There was very little fun to be had in either of those episodes. Seven, though, was pure story and character, and I adored writing it. I’m so proud of that script and seeing Rose and Greg perform it live was a special privilege. They sat at either end of the table, wielding their dialogue like weapons, constantly attempting to outmanoeuvre each other, all the while showing just how much hurt and compromised love there was between them. The rest of us sat in stunned silence, riveted and uncomfortable, feeling like we were spying on something raw and ugly and personal. I think in that moment the full scope of what we were doing began to dawn on me. The fact that, in bringing on board the range of brilliant people we had, The Pact had become something far more than a little isolation project to keep us all occupied. What was taking shape was a complex story of very human failings, a story without villains, a compassionate but honest look at addiction, guilt and consequences. That day was, in the end, overwhelming. Rose and Greg’s stunning performance set the tone and after that we worked through every episode slowly and meticulously, following it up with lengthy discussion about what we felt was going on for the characters, what the meaning of that particular chapter was. By the time the read was done, the day was almost over. We moved into some workshopping and one-on-one discussions, but we were out of time for the planned rehearsing. Which, in the end, was fine because in bringing as many of us together as we could the day had achieved its objective. We all, myself included, walked away with an increased understanding of this thing we were making but beyond that, with a unified sense that we were making it together. That despite the separation inherent to creating something in a pandemic, we were a team working to realise something special. Now we just had to finish the thing.

0 Comments

A little bit about Peter Blackburn. We first met working on The Trial of Dorian Gray. Kashmir introduced us, thinking that Pete would be a great fit for that script. His reputation preceded him and I went to that first meeting apprehensive, suspicious that he would be a haughty wanker looking down his nose at our little indie theatre project. Not because anything I’d heard about him indicated that this might be the case, but rather because he is held in such high esteem in the Melbourne theatre scene that it was hard to imagine he would want any part of our project without lots of money and lots of changes. It took maybe two seconds for me to be disabused of that stupid notion. Sometimes you meet people with whom you instantaneously connect and that was one of those times. Pete is not only one of the kindest people I’ve ever met, but one of the wisest, most committed, and most formidably talented. He works without ego; committed only to the realisation of the project as best it can be. He has a singular ability to draw incredible, layered, natural performances out of actors and tends to finish a project with the fierce loyalty of everyone involved. Pete deserves the same evaluation I have of Rose; if you can get Pete Blackburn to direct your play, get Pete Blackburn to direct your play. Or, in this case, web series. That the idea of bringing Pete on board didn’t occur to me earlier is indicative of my own idiocy. I’d even sent him early scripts and outlines for feedback without ever thinking to suggest more direct involvement. Pete, after all, had been on board to direct our planned next show, Three Eulogies for Tyson Miller before lockdown happened, and with The Pact more or less replacing that play in our schedule, moving the whole team over probably would have made sense. It was after we decided to reshoot the first ep and I called Pete for feedback about what we’d gotten wrong that a very obvious realisation clicked into place. At some point in that phone chat the idea of Pete directing the whole series was raised and that was that. He connected up with John, Rose and the rest of the cast, and the ball started rolling. Episode one would be reshot, and then they would roll straight on to the rest of the series. And under Pete’s guidance, we wouldn’t have a repeat of the same issues with episode one. Well, not a repeat anyway. As the first cut was turned in of the reshot episode one, it became clear that this would be a particularly tough nut to crack. The problems, I stress, were not the direct fault of anyone involved. It was a confluence of minor things that all together meant the episode designed to kickstart the series was not making for especially compelling viewing. The script needed a tighten. There were eyeline issues. Tonally it came off as too dour and downbeat. People say endings are hard, but I can promise you that they are nowhere near as hard as beginnings. After all, the challenge of ending well won’t matter one iota if your story hasn’t drawn in an audience, and it’s very tough to do that without a strong opener. The new version was a marked improvement on what we had, but another round of collating feedback illustrated that my reservations were not paranoia; the problems were problems. My reluctance to reshoot remained. This should have fixed everything. But then, if the me of two weeks previously was to be believed, this should have been an easy project. And that was proving to very much not be the case. Things got a bit heated as we discussed what to do about episode one. The consensus was largely against reshooting. At that stage I was more or less willing to accept being outvoted, but that didn’t change my doubts. Episode two came in and, while it was solid, it was hard to see it as proof that our concept overall worked. Episode two is very much a table setting instalment, paving the way for the fireworks factory without getting there itself. Which made me anxious to see three and four; three includes a major reveal that sets up the remainder of the series, while four works as a kind of climax to the ‘first act’ of the story. The two episodes were filmed back to back and so, as new scripts came in and I edited them, I waited. Some issues with three meant that four was ready first; it was sent through shortly after restrictions were eased enough for us to have some friends around to dinner. So, rudely, I stepped into my room to watch the cut. And in moments, we were vindicated. Four was brilliant. Chris and Rose infused so much anger, hurt and betrayal in their performances; a pay off to the tensions between their characters in episode one. They brought Kate’s searing script to breathtaking life, sending me running back to the dinner party overflowing with exhilaration. Kashmir felt the same, and that catapulted us into a bold new conversation. We weren’t convinced episode one was working. And at VCA I had been taught over and over that where possible, you should start the story as late as you could. So what if episode four became episode one? If we started with a showdown between two siblings, the culmination of years of unspoken resentment and hurt. What a statement of (accidental) intent that would be. There’s no harm in entertaining a bold idea, but it’s not always worth seeing through. The episode was satisfying because it followed from something we’d already seen. In isolation it would be a great acting showcase, but not an effective start to a series. Still, it proved what we were capable of and, to me, demonstrated exactly why episode one would have to be reshot again. This was now the standard we had to try and reach wherever we could. Three, meanwhile, had its own issues. The aforementioned reveal didn’t seem to be landing the way we thought. But in a case where the bold idea was exactly the right move, we came up with some drastic cuts that reshaped the episode into the gut punch it needed to be. Several people have now reported that three is the moment where they go from mildly interested to fully on board with the series. The first of many examples to come of how a good edit can transform something. Altogether we were well on the way. Five and seven were in the process of filming, as we were yet to find the cast member we needed for six. Everything was looking good. But as Covid restrictions lifted, the big sales pitch of what made the series unique began to lose relevance. The succession of trial and error coupled with the growing scope of the show had slowed everything down far more than we had planned. Which left us needing to work out a way to get as much filming and editing done as quickly as we could, without sacrificing the standard. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed