A few years ago I was listening to a radio interview with an author who said ‘I write because it’s cheaper than therapy’. At the time I laughed knowingly without giving any thought to what the statement actually meant. My feeling then was it spoke to the idea that we’re all sexy tormented artists grappling with the weight of the world. The truth is way more mundane than that. My personal theory is that writers write to try and make sense of things. Whether it’s a novel, a short story, a review or an article, just about all writing is a response to something experienced or witnessed, refracting reality through a worldview, narrative and sensibility that makes it all just a little more palatable. To explore this a little further, I’m going to talk about Community. I first got into the show in around 2012, because it was a cult favourite that a lot of my friends were watching. I followed suit and predictably loved the tribute/concept episodes and the dark humour, but there was plenty I didn’t appreciate. Like the occasional episodes that went dark and sad instead of funny. Or the fact that the show spoke endlessly about the importance of the central group’s connection without, for my money, actually doing the work to build that connection. I found the more conceptual third season a pretentious mess of half-baked ideas and I started to get frustrated at the ongoing media narrative suggesting Community was an underappreciated modern classic. So much so that I wrote a lengthy blog post about the fact. I think it might have been like, the second thing I posted here. Reading that post again makes one thing abundantly clear; I really, really did not get Community. And I don’t think I could have, at the time. To explain what’s changed, let’s get personal. I’ve spoken before about 2015 as a bit of a low point for me. There are several reasons for this, but I think the key one is that it was the first year where I started to realise I wasn’t the person I wanted to be. I’ve always gone through bouts of insecurity and uncertainty, but 2015 was something else because almost overnight my life changed in intangible ways that it took me a long time to wrap my head around. For a couple of years prior, I’d lived a carefree life of casual work, partying and writing. I had good friends all around me, a fun party house that was always full of life and collaborators helping me get my work on stage. Then things changed. I moved into a cramped, dingy apartment that had a constant sense of wrongness about it (I found out later somebody had been murdered there), the kind of place people didn’t really want to visit. My housemates weren’t around often, understandably preferring to spend time with their respective girlfriends. I started working a dull job in a distant, dodgy suburb that was a two hour commute each way, leaving me barely any time for anything other than work. The newfound distance from everyone who had previously been such major figures in my life just underlined a growing sense of worthless isolation. Somewhere along the line I had taken a wrong turn and couldn’t seem to find my way back to the previously promising road I had been on. I was stuck somewhere between adolescent and adult, living a sad facsimile of my previous life all the while preoccupied by a sense that I needed to grow up but with no idea of how. I had reached the end of my Masters of Screenwriting with no clear path forward and started to realise that my hard-drinking lifestyle was no longer the norm. Excess is a lot less fun when you’re the only one indulging in it. In fact, up against the seemingly sudden maturation of those around you, your own behaviour can be cast in a new light that shakes your sense of self to the core and leaves you wondering what’s wrong with you. I lost confidence in my writing. I lost confidence in myself. And through all this, during my lowest ebb, the sixth season of Community was coming out. Now, the sixth season is nobody’s favourite. Half the main cast have been replaced, the sharpness of the writing isn’t the same and there’s a sense of sadness to the whole thing that makes it feel dreary compared to the crackling wit of earlier years (ignoring, obviously, the Dan Harmon-less fourth one). And yet the more I watched the more I found myself developing a new perspective on Community and, in particular, on protagonist Jeff Winger. I can’t imagine anyone is reading this without at least a basic knowledge of Community, but for context the series starts with Jeff losing his job as a lawyer when it is discovered that he never went to law school. In order to be reinstated as quickly and easily as possible he enrols at the highly dodgy Greendale Community College, to him a humiliating step down. He quickly gets drawn into the lives of a gang of misfits with whom he forms a study group and welcome to the plot of our sitcom. What is unique about Community – apart from everything – is Jeff’s development. Naturally, his arc early on is the growth of genuine caring for his newfound community (geddit?). But as the series continues something kind of interesting happens. The show starts to call him to task, even outright suggesting in approximate series midpoint Remedial Chaos Theory that Jeff is holding the entire study group back from actual development. This subtext becomes text in season six when, necessitated by the many departures of main cast members, the show starts to centre on Jeff’s growing anxiety that he will be the last one left at Greendale – a fate his season one self would have seen as worse than death. The final season mines genuine (but still funny) pathos from his growing desperation to hold his found family together as the last remaining younger members start to look beyond college to what the next stage of their lives might look like, right as Jeff starts to realise that the next stage of his life is this. In retrospect, it’s easy to see why 2015 me might have found the sixth season of Community so affecting. But honestly, at the time I just assumed that its new dour sensibilities suited my mood and didn’t examine the correlation any further. Understand, the moments were rare in which I could admit even to myself that my real anxiety was that I had been left behind by everyone I cared about. Of course, insofar as stories in real life have endings my 2015 had a happy one – I got out of the murder apartment, won a screenwriting award that changed my life, reconnected with my friends and entered a period of renewed artistic passion that included a handful of genuine successes. But I still found myself thinking about Community’s ending, even divorced from the mindset that drew me to it. As somebody who has always been obsessed with stories, I used to be troubled by the gap between the appealingly flawed but ultimately great lives and personalities of characters on screen and my own. I think I lived in fiction to such a degree that the messiness and ugly sides of my own nature became genuinely challenging to me, a kind of signifier that I was wrong somehow. Maybe that’s partly the reason that Mad Men always spoke to me so much; after all, the characters on that show are largely trying to come to terms with the fact that the perfect life they propagate is so vastly different to their realities. In Community, every character is dealing with that divide. Jeff just takes the longest to realise it. Every single member of the study group has either let themselves down in some way, is not capable of dealing with the real world or both. The fact that Jeff and Britta are the last of the original study group remaining by the end might have been due to the increasingly difficult schedules of core cast members, but it also makes perfect sense that the two most initially self-assured characters were the two most deluded about who they really were. The sadness of Community, then, was not unique to season six. On rewatch it slowly became clear to me that it had been there all along, that the through-line to the wacky adventures of the study group was a fundamental sense of failure that they all struggled to contend with. The reason they clung so desperately to each other (in increasingly pathological ways) was because they didn’t think anyone else would accept them. Other sitcoms might poke fun at their characters’ co-dependency, but would never ultimately explore the dark why of the fact. Community did, and that’s one of the reasons it was so bold and subversive. For all the kooky sitcom trappings, it reflected real life in a distinctly ugly way without losing sight of the bruised humanity at the heart of its characters. This is why Community is, for all its flaws, so much better than Scrubs or How I Met Your Mother or any of the other sitcoms I spent my teens and twenties watching. It doesn’t stop at what’s easy or digestible. It pushes into the gaping chasm that exists in all of us between who we are and who we think we should be, and in that place finds something hopeful. The best writing is a kind of therapy, but not just for the writer. The best writing reaches through the screen or page and tells the audience ‘I’ve been there too, and you’ll be okay’. And when you really need to hear that, there’s little as powerful.

0 Comments

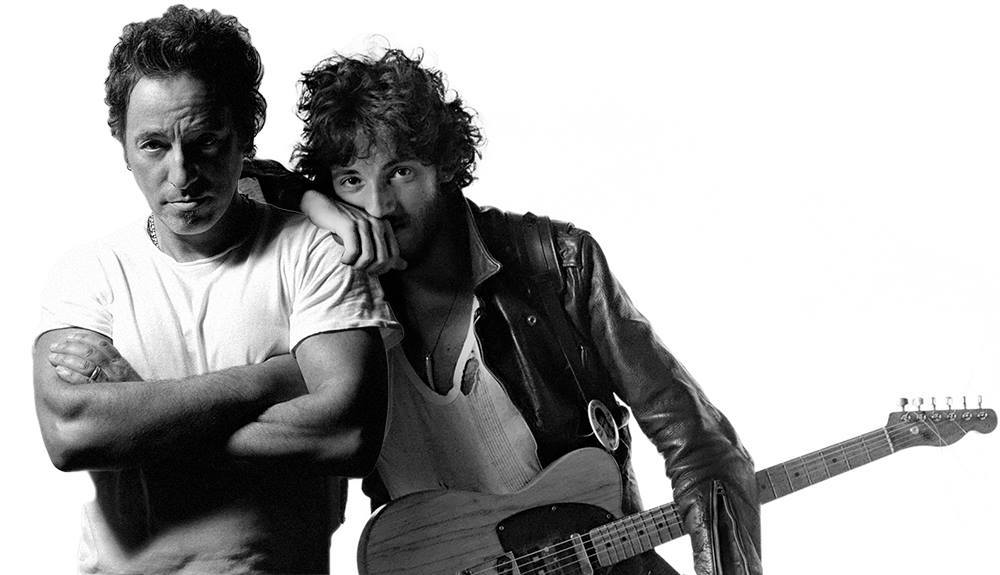

As of September 2019, it’s been ten years since I discovered Bruce Springsteen. I’ve spoken before about my longstanding and passionate love for Jonathan Tropper’s novel The Book of Joe, which I read in high school and immediately connected to. The Book of Joe tells the story of a successful author who became famous for writing an unflattering book based on his hometown, who is then forced to return to said town after his estranged father has a stroke. It’s not a perfect novel – it’s overwritten with a few unnecessary narrative diversions – but it’s so deeply felt and nakedly emotional that, as a small-town kid with aspirations of a writing career, it was close to revelatory for my sixteen year old self. It also is packed full of Springsteen references. The first time I read it, it was with a vague sense of ‘huh, maybe I should check that guy’s music out’. When I read it again a year later in 2009 I realised I would have to look up the songs to fully understand what the book was talking about. I started with Backstreets, a track that is a very particular motif in The Book of Joe. It was a pretty immediate sell; Backstreets is a passionate, mournful roar of a song – I remember at the time thinking it sounded like a voice on fire. I had to hear more. At the time, I had been asked by a friend to take part in a play of hers out in Warburton. Given that I was about a month out from my Year Twelve exams the worst possible thing I could have done was say yes. I said yes. And without getting bogged down in specifics, it was one of the best decisions I ever made, something that led to lifelong friendships, my current relationship, my first plays being performed and piles of valuable life lessons. But more immediately, it led to one of those dreamlike phases of passionate, hedonistic perfection that you only really get when you’re a teenager; nights of drinking around campfires, writing songs together and swearing lifelong devotion to each other. It was, at the time, like I was living two different lives; during the week I fretted about exams and rigidly followed the rules of my old-fashioned private school, but on weekends I entered a whole other world, one where normal rules didn’t apply and everything might as well have been taken from a sweetly nostalgic coming of age film, except it was real and better than any of those films could ever be. I remember one morning waking up on a couch outside, looking out over the misty hills and the trees. I sat there alone listening to Thunder Road and in that strange and magical way that music can sometimes achieve, my very particular emotional state was reflected back at me. From there the Born to Run album became the soundtrack to my life; all those songs of passion and escape, of getting out of your town full of losers, of locking up the house and stepping out into the night to see what was waiting for you, of soft infested summers and girls you agonised over. Did the songs make the time or did the time make me susceptible to the songs? It’s hard to say. But Born to Run will always be synonymous with a phase of my life that I’ll always hold dear. That alone would be enough for me to forever love Bruce Springsteen. Except Bruce has a habit of giving you far more than you could have hoped for or expected. In Wrecking Ball Springsteen tells us that ‘hard times come and hard times go; just to come again.’ And while I appreciate that in the context of his songs such messages tend to refer to the economic difficulties of the working class, it’s also reflective of something I’ve learnt more and more is true; that no matter who you are, happiness never lasts but nor does the darkness and that’s the way it should be. You need the bad to appreciate the good, and both will come and go. The idyllic time in my life that I’ll forever link with Born to Run ended, because of course it did. Secret romances and perceived betrayals left the friendships we swore would last forever in tatters and while reconciliations came it was never the same. In retrospect, the fact that the songs on Born to Run so perfectly reflected that time stands to reason, because Born to Run is very much about the end of innocence, about the last gasp of childhood idealism before the realities of the world set in. And for that reason, I still can’t finish a full listen of Born to Run without diving straight into Darkness on the Edge of Town, the starkly different follow up album that, for my money, serves as one of the most perfect sequels ever. 2010 was a very different year to its predecessor. I was broke and alone in the world, at a uni I hated without any of my former friends, working shitty jobs to make exorbitant rent and trying to wrap my head around the fact that all of my beautiful shining dreams about what early adulthood would be would not come true. It’s not that I had it especially hard, but no matter your circumstances the realisation that your life is not going the way you expected will never not be a challenge. Darkness, then, became the soundtrack to a different portion of my life. I would walk around the streets at night listening to Badlands or The Promised Land as a kind of defiant middle finger to a world that wasn’t giving me what I wanted. It was like Bruce was telling me to get back up despite the disappointments and the traps I seemed to be surrounded by; ‘you wake up in the night with a fear so real, you spend your life waiting for a moment that just don’t come; well don’t waste your time waiting.’ Later that year, when I finally hatched a plan to change my circumstances, to get into a job, university and house that I would be happy with, I clung to a different, far later Springsteen song. I played Working on a Dream over and over again as a kind of mantra. Every time my unpleasant circumstances threatened to get me down I whispered the chorus to myself; ‘I’m working on a dream.’ By the end of that year, I’d achieved what I set out to. I worked at Dracula’s (at the time a dream come true), I lived in a cool apartment in the middle of the city, and I had transferred to the best uni in the country. With Bruce as my guide I fought to change my circumstances and while in the grand scheme of things the victory was minor, it was real and it was mine. In The Book of Joe, the main character semi-jokingly says ‘there’s a Springsteen song for every occasion’. Over the years I learned the truth of that, in times both good and bad. In 2012, after my first serious breakup, We Are Alive became the anthem of hope and comfort that kept my head above water. As I entered a new period of creative and personal fruitfulness in 2013, I listened to the celebratory exuberance of Thundercrack on repeat day after day with a big smile on my face and spirits lifted every time. When I finished my Masters in 2015 and found myself with no clear path forward, personally or professionally, the mournful tracks on Tunnel of Love were like a gentle reminder that I wasn’t the only one who felt that way. And while so many of those albums and songs will always be linked to particular times, places and people, none of them were ever just a reminder of something past. I came back to them again and again, seeing new layers on every visitation. In 2016, as I entered a place in my life and career where I started to slowly shift out of the ‘aspiring’ category when it came to calling myself a writer, Springsteen’s autobiography became a kind of holy text for me, a beautifully written book that reminded me when I needed to hear it the most that while art and creative success are brilliant, they’re not everything. This sentiment led me to finally write a play about Bruce’s life, my own attempt at a kind of tribute to him, and a work I remain very proud of. At a certain point my appreciation, love and respect grew to encompass the man as well as the music. Springsteen’s philosophies, his honesty, his decency and his never ending drive and passion to continue experimenting and taking risks while at a place in his career where he has nothing left to prove became a perpetual source of inspiration, the ideal of what an artist could, and perhaps should be. Even as he nears seventy he keeps on giving. Next month two Springsteen films are hitting Australian screens. Western Stars, a sort of concert film/mood piece adaptation of his latest album, and Blinded By The Light, a movie that by all accounts captures exactly what it is to be seventeen and discovering Bruce Springsteen for the first time. In the trailer, we see the protagonist prowling the late-night streets, leaning against walls overcome with emotion as The Promised Land and Dancing in the Dark blare in his ears articulating all the things he struggles to say himself. Watching that hit me so hard because of the sheer specificity of that very familiar moment. There are other musicians I love, other careers I’ve followed closely and other songs that have provided a way to express the inexpressible. But Bruce Springsteen, for a decade of my life now, has pulled off the same trick again and again, providing an ongoing collection of reminders that no matter how bad things might seem, you’re not alone. Joy, love, pain, regret, defiance and hope; Springsteen expresses them all with a power and honesty that is singular. Art, at its best, makes whatever loads we all might be carrying lighter; whether offering an escape or a necessary reflection, making everything just that little bit easier to digest and deal with. Once I had a dream that I met Bruce. In fact I’m lying, I’ve had several of those dreams. But the one I’ll always remember is the one that rang the truest. I saw him, shook his hand, and said ‘thank you’. Then I left. Because after everything, what else could I ever say or do to convey how much his work has meant to me? The past decade of my life, representing the slow construction of a career and the slower growth into an approximation of adulthood, has been a messy, bumpy, sometimes ugly time. I haven’t always been the person I wanted to be. I’ve hurt people and let them down. I’ve embarrassed myself and been a pathetic, childish failure; a mix of arrogance and insecurity that sometimes makes me marvel at the fact that anybody has stayed my friend for more than a day. But beside the darkness sits the light. The wonderful people I’ve shared the journey with, the times I’ve had that I’ll remember and love forever, and the hard-won successes that were all the sweeter because I know I earned them. But the consistent voice that guided me through all of it belongs to Bruce Springsteen. And I can say, without hyperbole or self-consciousness, that none of it would have been the same without him. Thank you Boss. Here’s to the next ten.  As you may or may not know, recently my TV concept Endgame was a finalist in the AACTA Elevate Pitch competition. This in and of itself is a big deal; the winner gets some development support and the prestige of the AACTA name on their project, but every finalist gets to pitch onstage in Sydney in front of an audience of industry people. So, first thing Saturday, producer/friend Dan Nixon and I were flown up to Sydney to basically try and sell the show. I was not prepared. It’s been a busy time and to be honest, the Endgame pitch was at the back of my mind. I kept trying to make myself rehearse or even write out what I was going to say, but other things kept getting in the way and so I got on the plane Saturday morning with only the vaguest notion of what I was going to do. The moment we arrived at the Factory Theatre reality started to set in and so Dan and I ran through our pitch again and again. We only had two minutes to convey what was special about the show, but pretty quickly we settled on a pitch that felt right, engaging. Not that that in any way assuaged nerves as the clock ticked down and two really great pitches preceded us. We didn’t win, but given how deserving the pitch that did was, how clearly the creator understood her product and how perfectly she articulated her ideas, it was hard to be too upset about that. In the end I think we did well. We got laughs in the right places and plenty of people approached us afterwards to congratulate us on the pitch, give us their details and ask to know more about the project. It was thrilling enough just to be there and to see how much potential and marketability Endgame really has. For the project, it was a super energising experience and leaves me excited to see where it can go next. Sunday was pleasantly lazy; Dan and I wandered around the city, had breakfast overlooking the sunny harbour, browsed bookshops and drank beer at the Rocks before Dan headed off for his flight home, leaving me alone and ready to take Sydney by storm. By which I mean I drank Guinness and did some writing at the Irish pub near my hotel before being in bed by 8:30. The reason I was sticking around longer than Dan was because I had organised to have lunch with my agents Tara and Jerry on Monday. These are the two people responsible for changing my life almost overnight; Tara having sold the book rights to The Hunted and Jerry, visiting from LA, the one who sold the film. It was the first time I had met Jerry and it was great to be able to chat in person over lunch, to try and fail once again to adequately convey just how grateful I am to these two people. The AACTA pitch and the lunch with Tara and Jerry feel, in some ways, symptomatic of the totally different speed my life seems to operate at these days. If you told me a year ago that I would be regularly flying to Sydney for pitches and meetings, that I would be sending emails back and forth with major Hollywood producers and some of the biggest publishers in the world, I would have laughed you off while desperately hoping you were right. But in some ways the more things change the more they stay the same. Next week Bitten By Productions’ new show, a revival of my 2016 comedy The Critic, opens at the Butterfly Club for Melbourne Fringe. I’m super excited about this; the cast and director are amazing and the rehearsals I’ve sat in on have been uniformly brilliant. But, of course, independent theatre is independent theatre, by which I mean there’s no money and lots of competition, particularly during Fringe. So my time-honoured techniques of guerrilla marketing come into play; namely spending the day running around the city surreptitiously sticking up posters and leaving flyers in obvious places in the hopes that more people will see them and come to see the play. It’s a very stark difference from being wined and dined by publishers and agents or getting on stage at major industry events. But this, I guess, is my life now. For all that the most incredible and formerly inconceivable things have happened in the last six months, things just haven’t changed that much on a day to day basis. I still have my old commitments and I still have to trudge around trying to look casual while leaving flyers and posters in places I’m probably not supposed to. I wouldn’t change it for the world. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed