|

I have always preferred writing in first person. I find it far more natural to adopt the voice of a character and explore the narrative through their worldview than to take on the role of omniscient narrator. But that doesn’t mean I haven’t tried the alternative, to varying degrees of success.

I think the challenge I find when it comes to writing in third person is that it’s so much harder to explore what is going through a character’s head. In first person you essentially become the character and so articulating their experience is fairly straightforward but to do third person well you have to show rather than tell, and this is much harder, especially when you’re still trying to make the audience empathise. It’s no coincidence that Windmills and Boone Shepard, the two of my stories that have persisted the longest, were both written in first person. Boone’s wry, exasperated, self deprecating approach to his adventures is fundamental to the style of his stories while one of Windmills’ biggest strengths was always the contrasting perspectives of its three central characters. First person allowed me to dig deep and I think was an inherent part of the reason those stories have always been so important to me. And yet the time seems to have come where I have no choice but to kill that particular darling, at least as far as Windmills is concerned. I’ve been writing a fair bit in blogs lately about the current iteration of that novel, which I’ve been slowly working on over the last year, but one thing I haven’t mentioned is that, unlike previous versions, this one is in third person. Part of the reason for this is the condensation of the narrative. Originally Windmills took place in four distinct parts over several years, each told from the perspective of a different character. The current version essentially tells the same stories in a much smaller time frame, meaning they largely occur parallel to each other, and this made writing in first person much more challenging. I briefly considered pulling a George R.R. Martin and having the story alternate between the perspectives of three viewpoint characters, but it doesn’t really suit Windmills; certain extended parts have to be told from one character’s point of view while others require more jumping between perspectives. Some of this structure is due to the fact that this particular iteration of Windmills was originally designed for television, where I could be far looser about whose eyes we saw events unfold through, but in a first person novel that has as much going on as Windmills does that becomes an impossible task and so, to tell this story the way I felt I needed to, my only choice was to bite the bullet and shift to third person. It’s been a weird experience, to say the least. The writing hasn’t felt nearly as natural as previous versions, and yet reading back over it I think it’s significantly better than any of them. Third person has certainly given me the narrative flexibility I needed but that doesn’t change the fact that I’m so used to telling this story through the eyes of specific characters that taking a step back makes me feel oddly disconnected, like I’m not as invested as I have been in previous attempts. Of course part of this is certainly due to the fact that I’ve been working on various reworkings of Windmills for so long that it’s a legitimate surprise that I have any passion left for the story at all, but being unable to relay events in the unique voices of Leo, Lucy and Ed is weird. That said, I think it’s largely been a benefit. I mentioned above that third person requires you to show more than you tell and so I’ve taken this as an opportunity to introduce more subtlety and ambiguity to the narrative. I can depict the actions of the characters with the barest glimpse of their thoughts and let the audience put two and two together regarding the whys of their choices. It gives a slight detachment to proceedings, but I think it makes for a more interesting novel on the whole. I’ve always had a tendency to over-explain in my writing and telling the story this way kind of forces me to do the opposite in order to make it compelling. It’s a weird, uncomfortable step into new and different territory for me, but reading over the novel so far makes me think it’s working. When you’ve written a story as many times as I’ve written Windmills it’s easy to become set in your ways but important to be willing to break said ways to break new ground and give yet another version of the same story a valid reason to exist. If you want to progress as a writer you have to be willing to step out of your comfort zone in more than just the territory you explore. Even if it seems scary or like you have to say goodbye to something you loved, the results may just surprise you.

0 Comments

One of the first pieces of advice you’ll ever get when you set out to be a writer is to ‘kill your darlings’. It’s a phrase that refers to the practice of getting rid of passages, phrases, characters or subplots that you really like when they’re not serving the story properly. Generally speaking it’s a good rule; every storyteller will sooner or later find themselves in a situation where the only justification for including a certain story element is ‘but I really like it!’, which, simply put, isn’t good enough.

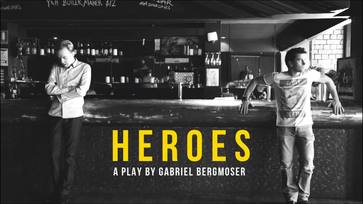

Bad stories come in many forms but the worst offenders tend to be stories that force the audience to put up with things that aren’t necessary or entertaining. It’s in these instances that ‘kill your darlings’ might have saved the narrative, as a writer who seriously interrogates the worth of every aspect of their story tends to tell a story worth hearing. Which brings me to Windmills. For those unaware (and I can’t imagine you’re reading this if you’re unaware), Windmills has long been the love of my storytelling life, a psychological thriller I first wrote in high school that I’ve never quite been able to leave alone, whether I’m adapting it into a play, self-publishing it as a novel, adapting it into a TV screenplay or, as I currently am, reworking it as a novel again. Windmills tells the story of Leo Grey, a teenager who makes a terrible mistake that haunts him for the rest of his life as his continued failure to do the right things leads to his moral decay and causes a domino effect that destroys the lives of those he cares about. The process of revisiting Windmills again and again over the last eight (!) years has been at times frustrating but ultimately satisfying as bit by bit I’ve gotten closer to what I think the story has to be. Of course, over such a long period there have been characters and plot elements added and detracted from the first draft. Some of these have helped while others have slowed down the process, but one character has managed both. Charlotte Laurent was never present in the original draft; in fact she first came into being as the protagonist of a companion novel I tried to write immediately after the first draft. Charlotte was the girlfriend and eventual wife of Dominic Ford, the drug lord antagonist of Windmills, and the companion book would have depicted her corruption in a way that paralleled Leo’s, leading up to a showdown between the two. The more time I spent on the novel however the more I realised it wasn’t working, and Charlotte’s arc ended up predominantly as backstory for the next version of Windmills, in which Charlotte herself became a supporting character. Maybe in part due to the fact that Charlotte was meant to be a protagonist but ended up being more secondary, she’s always been a big favourite of mine. As a character she’s innately fascinating to me; younger than the rest of the cast, she basically gets dragged into a world she doesn’t fully understand which proceeds to twist and change her until she is finally forced to decide where she stands. Charlotte is one of the few Windmills characters who eventually got a happy ending because she was one of the few I really felt didn’t deserve to suffer in some way. However, after Windmills won the Ustinov award and I started developing it as a TV series concept in earnest, some darlings faced the chopping block and Charlotte was chief among them. The reason for this was simple; Charlotte’s role in the story took place entirely in the extensive part of Windmills that followed the central characters out of high school, and the TV version of Windmills, tweaked in the interest of making it an easier sell as a young adult story, only leaves high school at the very end, meaning there was very little room for Charlotte to appear in any way that felt natural. I tried really hard but in the end the best I could settle for was a brief cameo at the end that didn’t touch on all the backstory or relationships she had originally had with the other characters. And with the new version of the novel closely following the TV series outline, it stood to reason that Charlotte’s role would remain unfortunately minor. Weirdly, however, for a character who never existed in the earliest versions of the story, the loss of Charlotte was something of a fatal blow. Try as I might, the story just didn’t quite feel like Windmills without her. Charlotte is so central to so much of the mythology that without her it felt somewhat like I was working on a high school drama that included some of the elements of Windmills without ever getting near the soul of it. Because, as I slowly learned, Charlotte, like Leo and Lucy and Dominic, is now part of the DNA of the narrative and without her it could never quite feel complete. So what do you do? Logic dictates you kill this darling, and yet instinct begs you not to. I struggled with this for a while but in the end I decided that I just had to persevere and try to ignore the gaping hole left by Charlotte. I couldn’t, after all, twist the entire structure of the story just to include one character whose role in the narrative wasn’t all that important. Well. The funniest thing about writing is how often you don’t recognise the obvious. Plot points can hit you in a wave of glorious inspiration that of course this is how the story is supposed to go, how could you have been so stupid? And once that realisation hits home, it becomes clear just how flawed the story was before, how this new development actually solves several issues you didn’t even know were there. For context, I’d planned the new version of Windmills to take place in six parts, each of which focusses on a different character (kind of like Skins with more murder and suicide and… well actually, just like Skins). The final part would come after a time jump, but the preceding five all took place in close succession, predominantly set in and around a school, starting with Leo Grey’s mistake and following the repercussions. But one issue I was finding was that the time jump, on paper, was a little too abrupt and jarring. Characters would be in one place emotionally at the end of part five and then turn up in part six having made major decisions or forged important new relationships off screen. What I needed was a way to show the passage of time, to set up the choices of the characters that would lead to the finale, to illustrate the changes so essential to the way it all wrapped up. What I needed was a fresh perspective to provide a new context to what we had already seen and what we were about to see, a new character who could raise the stakes and through whose eyes we could see the resetting of the board in time for the endgame. What I needed was Charlotte. Within minutes of this realisation the plan changed and Windmills went from six parts to seven. And suddenly issues I had had with the new version seemed to melt away. Plot points were set up more effectively, characters could be developed more thoroughly and suddenly the novel I have been working on feels like Windmills in a way it didn’t quite before, because a character I underestimated the importance of has finally come home, taking her rightful place among the rest and, in the way all the best characters do, shining a light on the obvious in order to allow the story to take the right path forward. Eureka moments like this make writing worth it for me. It often feels like there’s some magic at play, something beyond you just coming up with an idea in order to entertain people. I guess if there’s a moral to the saga of Charlotte’s triumphant homecoming it’s that killing your darlings is important, but trusting your instincts is infinitely more so. If the story seems to be pushing you in one direction, do what it says. Because nine times out of ten the story knows best.  There’s a few well known quotes that basically espouse the idea that what makes theatre special among all the storytelling mediums is impermanence. A book will last as it’s in print and people buy it, a film as long as there are copies in circulation. But theatre is different; even if a play has many productions and interpretations, each essentially represents a new artwork and once it’s finished, that’s it. Even the most long running plays will essentially offer a different experience night to night, as different actors step in or new inflections give new meaning to previously unimportant lines or moments. Despite our best efforts, theatre shows are never exactly the same twice, and that’s part of what makes them so thrilling and exciting. You are watching these actors live in front of you, and anything could go wrong at any moment. If you wanted to you could get up and run on stage and break the spell (don’t ever do that) or the lights could fail or a prop could break or someone could forget a line. Plays don’t have the luxury of being pre-recorded and every successful show is, in some ways, a minor miracle. Of course you can always film a play, but watching a recording is never the same in a medium that is designed to be live. And while some plays are turned into films or radio dramas, taking away the ‘live’ part of live theatre will always, to some degree or another, take something away. It’s for this reason that the end of any play is bittersweet. Especially in independent theatre, where your best efforts to fill seats will never quite bring in the numbers you’d ideally like and there will always be a couple of friends or family members you wish could have seen the show who didn’t. I have always been guilty of insisting at the end of any of my shows that this needn’t be the end, that we can go on to tour or do another season in a bigger theatre or develop it into a film or something, but on a certain level this isn’t much more than me being in denial about the end of something that meant a lot to me. Certain plays of mine have had encores. Beyond Babylon appeared at a couple of one act play festivals, while The Lucas Conundrum made appearances in regional towns after its first season finished. But none of these encores were extensive, and certainly none of them eclipsed the original runs. But after years of threatening to take shows on the One Act Play circuit one of them has managed to get there with some degree of success. Heroes finished its Melbourne run with good audiences and great reviews, but actors Matt Phillips and Blake Stringer saw potential to take it further, and so Heroes was entered in most of the Victorian Drama League festivals. While I was glad to see the life of the show extended, I didn’t pay much attention to the process. Until the show premiered at the Gemco festival and won best production. Then did the same at Mansfield. Then had a great one-off show in Benalla that led to offers for further touring engagements after that. And suddenly Heroes seems to be in the prime of its performing life, rather than in protracted death throes. In many ways Heroes is the perfect touring show. Coming in at a tight forty five minutes after a few edits, with a sparse set and only two actors, it is singularly easy to take from theatre to theatre. And furthermore, it happens to be pretty good. While this might sound like a case of the writer blowing his own horn, it’s hard to argue with reviews and audiences who sit in riveted silence but for the occasional gasps and laughs at all the right moments. I can’t tell you how awesome it felt to be sitting in the Mansfield festival last weekend and to hear total strangers telling each other that ‘you have to see Heroes’ and that it is ‘the one to beat.’ And while yeah, I have always been one to let my imagination run away with me, it’s hard not to wonder about the ongoing potential of this play. Performances in Brisbane and Sydney, maybe in conjunction with Movie Maintenance live shows, seem well within the realm of possibility, and if they work out then why not go further? Why not bring it back for another Melbourne season if it continues to win awards on the One Act Play Circuit? Basically, why not take whatever chance we can to get this play in front of as many eyes as possible? Heroes still has quite a few One Act Play Festival engagements to go and after that it’s almost a definite that it will make at least a couple of other appearances, but as far as I’m concerned the longer we can keep this train going the better. A radio play has already been recorded, so I guess that Heroes has already been preserved in a way that means a version of it will always be available, but for my money the best way to experience this story will be to see the live stage version, and even if an ongoing season/tour doesn’t get huge audiences, then at least we will know that we gave as many people as possible the chance to see a play that all involved are extremely proud of and, based on the accolades and response, is very worth seeing. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed