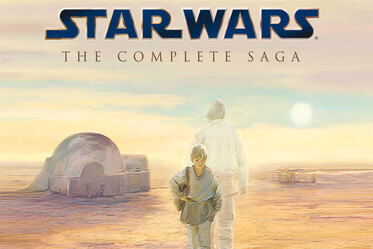

As somebody who still regularly buys Blu-rays predominantly for the collectability factor, I’m a little picky about which editions I splash out for. Take Star Wars – I’d been meaning to get a box set of the saga for years, but there was a particular version I was after, a version I was only able to find second hand. You’ve probably seen it; a light orange box depicting a painting of the Lars farm with the figure of little boy Anakin walking away beside the ghostly shape of adult Luke returning, all illuminated by the twin suns. It speaks of a story coming full circle, the son completing the work his father failed, a reckoning with the past. The fact that it’s a painting adds a somewhat mythic feeling to it. For better or worse you look at that box set and you see the representation of the complete vision George Lucas sought to bring to the screen. You can technically still get the six film ‘Complete Saga’ set, but the painting has been replaced with an ugly, generic picture of Darth Vader against a grey background that feels strikingly less significant. Given that this repackaging emerged shortly after Disney purchased Lucasfilm, it’s hard not to read into it a deliberate de-legitimising of the concept that Star Wars was done at six episodes in order to pre-empt a later release of a nine film set that will suggest you don’t get the full story until you’ve seen Disney’s sequel trilogy as well. Lending credence to this half-baked conspiracy theory is the marketing surrounding The Rise of Skywalker. With a faint whiff of desperation it has tried to convince us that what will hit screens in December is the long awaited conclusion to a beloved story, the keystone that will tie everything together, the ending we’ve been waiting for. JJ Abrams has talked extensively in interviews about how this film will bring all the threads of the preceding eight instalments together in a way that feels satisfying and inevitable, how this is what the entire franchise has been building towards since 1977. Which would all seem very exciting if the story hadn’t ended in 1983. Naturally I’m aware that Lucas occasionally alluded to a possible sequel trilogy over the years, but you can’t look at Return of the Jedi and not see it as a conclusion, just like you can’t look at The Force Awakens and not see a somewhat depressing undoing of everything the original trilogy resolved. By merit of its very existence the sequel trilogy shatters the assumed significance of the events of the original three films, forcing a scenario in which we need The Rise of Skywalker to succeed in order to give the whole story meaning. If, that is, we take the Disney films as canon. To clarify; I don’t think Disney Star Wars has been inherently bad. I’m an ardent defender of The Last Jedi and I think the Star Wars universe can sustain new stories from new creators – decades of the much beloved Expanded Universe proved as much. But I also believe that the original creator told the story he wanted to tell and anything additional will only ever be an addendum. But the legitimacy of Disney’s instalments has already been challenged by the existence of the Expanded Universe, which in its time had just as strong of a claim to significance and just as little support from George Lucas. So which of the two variations of ongoing Star Wars adventures is the real one? And does the lack of involvement from the man who created this story mean that neither can be seen as valid? Lucas, of course, sold Star Wars so there’s a decent argument that his approval or lack thereof isn’t important. But of course Star Wars is far from the only property with this question of canon hanging over it. The recent Watchmen TV series, serving as a present-day sequel to the seminal graphic novel, is probably the best new show I’ve seen in years. It’s also something Alan Moore, the original writer, remains vehemently opposed to. It’s also not the only ongoing sequel to Watchmen, with the comic book limited series Doomsday Clock offering an entirely different version of what happened next. So which is the real sequel to Watchmen? Both are high profile projects in their respective mediums, both have been well received, and both are detested by Moore. It’s easy enough to write them off on Moore’s say-so. But as a longstanding Watchmen fan I absolutely adore the TV show, which pays tribute to the original while charting a path entirely its own – the first adaptation I’ve seen since Hannibal that pulls this off with such evident ease and confidence. And maybe this is partly do with the attitude of the creators; Bryan Fuller (Hannibal) and Damon Lindelof (Watchmen) as showrunners have both proudly and openly designated their respective series as ‘fan fiction’, casting themselves as the pupil paying tribute to the master who inspired them rather than a new genius picking up the mantle. Lindelof in particular has been very thoughtful and even handed in interviews regarding how to approach his show when Moore, a man he reveres, spits on its very existence. Although it’s worth noting that Alan Moore, writer of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, is in no position to complain about people adapting other writers’ properties without their permission. The guy turned Harry Potter into the antichrist. It’s no secret that we’re living in an age where every popular property is being rebooted with or without the original creator on board, some with more success than others. Just ask the Terminator franchise. Since the high point of T2 in the nineties we have been given no less than four different continuities that continue from it. The most recent, Dark Fate, tried to stake its claim by bringing back Linda Blair and re-involving James Cameron to provide some story ideas along with an endorsement. Except he also endorsed the much loathed Genisys, stating – as he since has with Dark Fate – that it should be seen as the real third instalment. When even the creator seems to change his mind regarding what is canon, it’s hard to know why we should take any of this especially seriously. Do I see Dark Fate, Disney’s Star Wars or Lindelof’s Watchmen as canon to the originals? Honestly, no. I don’t think that thirty years after Adrian Veidt dropped his squid Alan Moore foresaw his plot having far reaching consequences in Tulsa, Oklahoma. But that doesn’t mean I enjoy the show any less or that I don’t think it has inherent worth. Since the dawn of time writers have been stealing from and adding to the stories that inspired them. If Homer and Shakespeare had been worried about canon or ownership then a lot of western literature simply wouldn’t have existed. That’s not to say that we should endeavour to steal or that we should value fan fiction over original stories, but a new creator playing in a sandpit built by somebody else doesn’t need to be a bad thing. One of the reasons I so strongly defend The Last Jedi even though I recognise its flaws is that, unlike so many other recent blockbusters, it feels like somebody’s vision. In its big swings for the fences, its attempts to tackle difficult themes and its willingness to look a bit silly in the process it feels like the work of a creator passionate about the world he’s been invited to explore but trying to tell his own story. It’s suggestive of the possibilities that franchises could offer; a world in which exciting new storytellers can put their own stamp on the worlds and characters that inspired them. And maybe it’s for the best to take a leaf out of Lindelof’s book and state outright that a property should be seen as fan fiction rather than rigidly canon. Some of the most beloved comics, after all, have featured characters like Batman or Superman in parallel universes that don’t impact the main storyline. Films like Logan or Joker, which adopt a similar ethos, demonstrate how this is possible within the film industry as well. It just remains to be seen whether this willingness to embrace a story’s outlier status can apply to franchises not based on comics to begin with. Of course these questions will be debated forever. Is Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, not written by JK Rowling, canon? What about the Fantastic Beasts films, which are? Is Halloween 2, H20 or last year’s Halloween the true sequel to John Carpenter’s original classic when they all claim that status? Or, as George RR Martin loves to say, how many children did Scarlett O’Hara have? The book says one thing, the film says another and neither really matters because it’s all made up anyway. Questions of ownership are important but let’s be real; if George Lucas ever was planning his own Star Wars sequel trilogy then the reason it never happened is because most ‘fans’ loudly and persistently told him he’d ruined his own stories. And he’s far from the only once-beloved creator to later be accused of screwing it all up. Most consumers, in the end, don’t really care who’s telling a story or whether it’s been given some ersatz stamp of approval as long as they’re being told a good one. The notion of canon is an arbitrary construct that only matters if, like me, you spend way too much time worrying about the mechanics of stuff that never happened rather than how much enjoyment said stuff is bringing you.

2 Comments

It’s that time of year again, in which I go through the output of Bitten By Productions in the last twelve months and evaluate what went wrong, what went right, what we’ve learnt and what’s coming next. I’ve done this three times already; looking back at our first ten plays before a breakdown of our shows in 2017 and 2018 respectively. The value of these little pieces is really more for me than anyone else – I think it’s good to arrange your thoughts on the year gone before diving into the next – but if you are interested in the ongoing challenges inherent in running an independent theatre company, then read on. It’s no secret that 2019 has been an incredible year for me, revolutionary in how rapidly and thoroughly my life changed. As such I’d be lying if I said that the two of my plays produced by Bitten By are really at the forefront of my thoughts as we reach the tail end, but both came with lessons both inspiring and sobering that are worth unpacking. So, lets kick off with the play that in retrospect indicated the degree to which everything was about to change. The Trial of Dorian Gray The Trial of Dorian Gray is not my best script. I think on a text level it has a lot going for it; deeper and more thought provoking themes than most of my previous works, a take on a classic that I personally think is quite fresh and a twist that likely counts among my best. But it has problems too. Structurally it might have benefited from bigger, clearer turning points and the dialogue probably verged on repetitive and didactic. In development, it continued in the tradition of two handers I’d written like Heroes and Beyond Babylon; battles of wits between two characters building to a devastating final reveal. But two handers are difficult and while Heroes (a contender for the best play I’ve ever written) moves fast and regularly shifts the stakes and the audience’s understanding of what is going on, Dorian sat a little closer to Beyond Babylon, at times playing out largely as a lengthy philosophical debate that probably came off to some (or more) as pretentious. Hopefully engaging, but rarely surprising. What’s not in dispute is that director Peter Blackburn and his team did an incredible job, in the process delivering Bitten By Productions’ most successful show ever. I knew from the start that Pete was the right person to tackle this piece. From our first meeting his understanding of the text was evident. We hit it off brilliantly and so began one of the most gratifying development processes I’ve ever gone through. Lengthy phone conversations excitedly talking through ideas populated the months leading up to the show, as Pete and his incredible hand picked cast turned a talky script into something layered and sexually charged, employing projection to make the play both visually striking and utterly haunting. Pete’s reputation in the Melbourne theatre scene also drew eyes. Major theatre and film figures came to see the show based purely on his involvement. Tickets sold fast and before we even opened our two-week run was sold out. We extended the show by another week only to sell out again. Word seemed to be spreading, despite the Midsumma season and faulty air conditioning meaning that audiences were contending with some truly oppressive heat. The riveting performances by James Biasetto and Ratidzo Mambo got huge amounts of well-deserved attention. Reviews weren’t uniformly positive, but the critics that loved it really loved it – and a lukewarm but ultimately favorable review from a famously harsh critic for The Age marked the first time in my career – and Bitten By’s – that a major newspaper had paid attention. That was a bit of a milestone. ‘Milestone’ feels like the right word for what Dorian ultimately represented. There was a sense that we’d moved up somehow, that we had put on a show that could and did contend with the best the Melbourne scene could offer. The fact that The Age didn’t tear us to shreds was in many ways testament to this. Beyond which, the lengthy philosophical debates the followed every performance and the generally excited responses indicated that this show had landed in a way we couldn’t have anticipated. Coming at the very start of 2019, after a preceding year that creatively and personally had been a bit grim for me, Dorian felt somehow pre-emptive of things to come, a great start to a great year and, thanks to the work of Pete and his team, a new and glowing standard for Bitten By Productions that we would have to strive to match going forward. The Critic Internally, we’ve had issues at Bitten By regarding planning ahead. The argument has been made that we should have every year’s season mapped out well in advance, with venues, dates and directors locked. In a perfect world this would be the case, but the world of independent theatre is far from perfect. People’s circumstances can change fast and drastically and it’s difficult to lock in a team a year in advance of a low-paying indie production. So, while we started the year thinking that it would be closed out with my Ned Kelly play Wild Colonial Boys and Kath Atkins’ comedy Eyes Wide Woke (more on this shortly), a few issues cropped up that changed the plan. I knew, for all that I was proud of Colonial Boys, there was something missing (that something being that it was a story more suited to the page than the stage) and Woke started to look more and more like a better fit for Midsumma than for Fringe, where we had looked at placing it. So, instead we decided to follow 2018’s model of reviving a well-received earlier show of ours for a Fringe season at The Butterfly Club before following it with a regional tour. We Can Work It Out had hit big in both 2015 and 2018, so bringing The Critic back made sense. The thing about indie theatre is that often you’ll have a small show that you’re really proud of but doesn’t get seen by that many people. As such, while I don’t love repeating myself, there’s something nice about giving a well-liked but underseen show a second chance. After the success of Dorian and We Can Work It Out, we were confident that a new production of The Critic could be a big success. We didn’t quite follow the same model as WCWIO 2.0. For that show we had largely carried over the same cast as the 2015 iteration, but with a new director it quickly became evident that it was a whole new take on the material rather than a belated extension. So for The Critic we shed early any pretense that this was a straight revival. We approached Rose Flanagan, who had stolen the show as an actor in 2016, to direct and the decision was made to cast again from scratch. Rose took to direction immediately and brilliantly. I was able to take a step back and let her handle just about everything. She assembled her cast, booked rehearsals and shaped the play in her own image, pulling it together with skill and confidence. It didn’t take long for all of us to get really excited about the potential of what this could be. But. There were big, big limitations that only fully became clear as the season neared. The first was the 5:30 timeslot The Butterfly Club had given us. It hadn’t seemed a problem, until we looked at ticket sales and realised that, despite our best efforts, they weren’t inspiring. The play ran over predominantly weeknights and half an hour to get from work to the theatre is tight. Then, of course, there was the Fringe factor. Festivals are always competitive and Fringe especially so, but every previous festival show of ours had been based on a known quantity (Moonlite, WCWIO, Dorian), allowing it to stand out. The Critic, despite a premise that had the potential to appeal to an audience of predominantly artists, didn’t quite have the built-in audience of a show about the Beatles. So, despite the play itself being fantastic and getting heaps of laughs, audiences were slim. We did our best to plug and promote, but given the circumstances there was only so much we could do. Resignation to The Critic being another excellent but underseen production set in. Then, proving that Dorian had elevated us to a new level, The Age reviewed us again. This time, it was unquestionably positive. And audiences for the last three shows ballooned. It wasn’t Moonlite or Dorian numbers, but it made a huge difference. Further vindicating was the regional tour that followed our Fringe season. While audiences were still a little sparse, they actually increased from We Can Work It Out and the show was totally embraced by those who saw it. The regional tour took The Critic from breaking even to profit, which despite the challenges meant that it was no disappointment. Which is a relief because the work Rose and her cast put in absolutely deserved to be seen. Still, it eradicated whatever hubris I’d carried over from Dorian. One play being a massive hit doesn’t mean the next will, especially when the former is based on a known quantity and the latter is not. It taught me that if we are going to tackle Fringe again, it will be with another property people know and recognise, or else some other factor to really make it stand out among the crowd. Because the Fringe crowd is really bloody big and even the best shows will battle to be seen. Next For a few reasons 2018 marked our quietest year since 2015, with only two productions and only one of them being a new work. This in and of itself wasn’t the worst thing in the world; it gave both shows plenty of breathing room and avoided the mistakes of 2017, the year in which we packed three shows in before June then added a fourth near the end of the year when everybody was getting ready for the holidays, meaning that Springsteen and Dracula (known quantities) hit while Heroes and The Commune floundered. The Critic, thankfully, wasn’t in competition with any of our other plays, something that probably would have spread us too thin and killed it. But I am hoping next year sees more than two shows take the stage. First up is Eyes Wide Woke, directed by 2019 MVP Kashmir Sinnamon (whose work as producer of The Critic kept that ship steady to the last). The first play from my former Movie Maintenance co-host Kath, it’s a very, very funny piece that will likely hit a bit too close to home for some in the audience. Already it seems to be making ears prick up, and I’m really excited to see how it goes. Unconfirmed but likely following it around July or August is Three Eulogies For Tyson Miller, one of the most personal plays I’ve ever written and one that, availability permitting, will hopefully see me reteaming with Peter Blackburn. But Pete is rightfully very in demand, so we’ll see how we go. Even more unconfirmed is another Fringe show. At the moment it’s looking like we will have a new play by a new writer based on a known quantity that, all going well, will take that spot. It’s a concept that is very cool and will absolutely appeal to a big audience, but it’s a long way from a sure thing. Obviously plans are hard to make and harder to keep in a constantly shifting scene, but if this does end up being our slate then I think it’s a pretty exciting one. Kath’s work on Eyes Wide Woke and the ways in which it has energised our whole team is just proof of why we need to be constantly bringing in fresh voices and steering into uncharted territory wherever possible. 2019, thanks to the stellar input of new blood like Pete and Rose, made new horizons all the more possible and by the looks of it 2020 will see us vaulting them with ease. Recently I was talking to a writer friend about a potential career opportunity that I thought he’d be perfect for. In order to pursue it he had to provide a few writing samples that illustrated his best work, so I asked; what’s your calling card? What, for you, is that one piece of writing that you’ll always automatically put forward as evidence of what you can do?

Most emerging writers, I think, have that piece. When we’re starting out our body of work tends to be a mix of the things we’re proud of and the things that we wish would just disappear. But usually there’s one story that stands out. Whether because we have a great feeling about it, because it’s the one that people most strongly respond to or, in many cases, because it achieved enough genuine industry attention for us to believe it’s good even if we don’t know why. For a long time, that piece for me was Windmills, and the reason is a mix of all of the above. Windmills, in its first version written in high school, was the first story of mine that seemed to get great feedback from even outside my immediate friends circle. I knew pretty much from the moment of putting fingers to keys that there was something different about it, that it was, somehow, special. And over the years enough evidence crept along to maintain that belief; interest from agents and publishers and, of course, its award win in screenplay form. Understand that for the most part writers don’t actually know if what they’re writing is any good. I mean, time and experience hopefully gives us a decent ability to gauge if something is working the way we want it too, but we’re always too close to know for sure. That cuts both ways; things that we’re sure are brilliant can be roundly rejected, things that we don’t think much of can be snapped up and celebrated. It’s discombobulating and can result in a strong sense of imposter syndrome. If you have no idea which of your stories has merit, then how can you possibly make a viable career? Windmills, however, was the rare case of internal and external belief lining up. Because I’d worked on it for so long in so many different versions, and because the initial act of writing it was a genuine game changer for me, I had long been convinced that it was the one; the project of mine that was special and would make my career. So any time anyone important asked to see some of my writing it was the Windmills pilot that I gave them without a second thought. And sure, that approach made perfect sense. Putting your best foot forward is only logical, especially when you’re not sure how to replicate what it was about that best foot that made it work. As the classic saying goes, if it ain’t broke, don’t supersede it with a different calling card. In the meantime, the vindication of seeing Windmills do so seemingly well provided an excuse for almost all of my attention to go into seeing it realised. When, last year, both the novel and TV versions of Windmills were rejected by heavy hitters I’d been trying to get it to for a long time, I was gutted. It left me totally unsure of how to proceed, wondering where I’d went wrong. I had been so sure that Windmills was finally ready. But here was a strange new issue; because I’d never totally understood what worked about Windmills, I had no clear insight into what didn’t. The project, after a decade of work, had turned into a big, ungainly mess that I couldn’t see clearly anymore. My calling card, my destined big success, whatever; Windmills might have advanced my career and my abilities as a writer but my conviction of its worth had also held me back. It wasn’t that I hadn’t written other things in the time I was working on Windmills, but everything else was secondary to it. And that had to change. If I was going to create a career, I needed to write something new, something that could be just as much of a calling card but, crucially, would not be my only calling card. It’s still staggering to me how quickly The Hunted both came together and found a home. The first version of the story had been rattling around since mid-2017 (back when it was a short horror novella called Sunburnt Country), but the actual process of turning it into a novel only took about a month. When I sent it to my now agent she suggested a few rewrites, I did them, she sent it out and within a month the book and film deals were both secured. It was the most painless and rapid development and acquisition process, something that seems increasingly insane when I remember that The Hunted was a total gamble; I wrote it at least in part to prove I could do something different but I had no idea how it would be received. I certainly didn’t anticipate it would garner the response it has, but here we are. In the end, all it took was letting go of Windmills. That’s not to say that I’ll never revisit it or that Windmills won’t eventually be realised in one way or another, but that the key to my career reaching a new level was to finally take the plunge and put aside the project that had dominated my life for far too long. I’m still proud of the Windmills pilot and it’s still something I’m happy to give prospective employers as proof of what I can do. But, crucially, it’s no longer the only thing I have. In diversifying my slate I now approach every meeting or discussion about writing stuff differently. Windmills isn’t for you? Try The Hunted. Or Nelson and the Gallagher. Or Boone Shepard. Or Below Babylon. Or Three Eulogies for Tyson Miller. Or We Can Work It Out. I’m proud of them all and yet none of them have anything in common with each other. Calling cards are important. But don’t put all your eggs in one project. Take risks, stretch your creative muscles and see what you end up with. Because the great thing about not being able to see every story clearly is that you never know which one might change your life. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed