This is the fifth instalment in an ongoing series examining the lessons learned from early works. Read Part One here, Part Two here, Part Three here and Part Four here. *** I’ve written a lot – a lot – about the process of writing Windmills/Where The End Began. But what I’ve never really delved into was how I came to write the TV pilot version that won the Sir Peter Ustinov Award and changed my life. It’s funny – the award was such a singular watershed moment for me, one I’ve discussed so much in blogs and school talks and interviews, but I’ve never seriously examined how I won it. Look at the context – by 2015 I’d been writing consistently for a decade. But I’d never, by anyone’s estimation, had any real success. Yeah I had a bunch of produced plays, but with the exception of a couple of rural youth theatre productions, I’d produced them myself. Likewise anything I’d published, in print or online. I’d never been paid for a piece of my writing. I’d never won or been shortlisted for any awards. Most reviews of my work were tepid. To clarify for anyone following along – this was pre the relative success of We Can Work It Out or publication of Boone Shepard. As I alluded to in my last blog, 2015 was a bad year for me in many ways, the first time I started to really wonder if I was barking up the wrong tree, when I first understood that the only person whose word I had for me being a halfway decent writer was my own. The best thing I had to cling to was my acceptance into The Victorian College of the Arts’ Master of Screenwriting, a selective course with a decent hit rate of alumni becoming successful writers, but by the start of my final semester there in 2015 I wasn’t feeling all that warmly towards the course. I’d come into it with a combination of arrogance and excitement, believing that my preternatural writing abilities would wow everyone, that I’d be taken under the wing of a mentor who might kindly correct a couple of minor shortcomings then usher me on my way to the big time. Not so. I’d quickly been intimidated by the abilities of everyone else. My ideas were met with a collective shrug. The tutors were quick to point out glaring issues in my writing that I’d never considered before. My response to all of this was to turn defensive and dismissive. As I’d tell anyone who listened, the course was trying to make us write by numbers, everyone was trying to bastardise my brilliant ideas, the tutors just didn’t get me, etc. I was insufferable and tiresome. But really I was just deeply insecure, a young writer starting to realise that he wasn’t as incredible as he liked to believe. Maybe this is why I floundered so much in my first year at VCA. The final outcome of the course was either a feature film script or a TV pilot and pitch bible, something we in theory would work on for the entire year and a half we spent there. I went in planning to write a feature adaptation of Below Babylon. When nobody seemed to think that concept was as awesome as I did, I pivoted to reworking my play Reunion for the screen before jumping to a not-especially-original concept about money counterfeiting then a black comedy show about a uni student moonlighting as a hitman (several years pre-Barry, this idea would later be re-developed in my podcasting days as an aborted web series called Mel MacDuff) then back to Reunion again. None of this was a waste – for example there was a lot to be learned in taking a small scale, contained stage show and trying to turn it into a Hangover-esque caper comedy film, but by the end of 2014 I was realising with a faint sense of desperation that I had no passion left for Reunion, that I’d pushed the themes and concept as far as they could go and I couldn’t spend another six months working on it. Which left me with the problem of what I’d write instead. It was over the summer break that I wrote, almost on impulse, the Windmills sequel manuscript. And as I revisited these characters who had been such a massive fixture in my writing life, the blindingly obvious became clear to me. I needed a new concept that I had enough passion for to see me through to the end of the course, but one which knew well enough to not be set back by starting from scratch. Windmills, arguably, was the only thing I could have written at that point. Looking back on this, I feel so sorry for my tutor, Peter Mattessi. He’d already endured my flip-flopping between projects and my poorly formed understanding of what I actually wanted to do. He must have been so exasperated when I got back from the holidays insisting that no, this idea was the right one. But, bless him, he rolled up his sleeves and got to work helping me shape the story into one that could work on TV. Here's the thing about Windmills at that stage – yes, it had been the biggest part of my writing life so far, but it had also never had any real external input, never had a firm editorial voice to suggest what I should or shouldn’t do with the story. Consequently there were a lot of aspects I’d always taken for granted that Peter challenged. The great thing about Peter as a teacher is that he has this unique ability to ask tough questions without ever coming off as adversarial. This meant that the petulant defensiveness that had characterised my first year at VCA had nowhere to go, and I had to instead consider Peter’s points. And he had a lot. He interrogated the inciting incident and the end-of-episode cliff-hanger (both of which would eventually change). He pulled me back when I went too dark or too baroque. He kept me coming back to real emotions and relatable themes that stopped the story from becoming just, in Peter’s words, ‘bad people doing bad things to each other.’ And look, maybe that first year at VCA had humbled me. Or maybe it was a few too many bad reviews or a sense that I had to do something to change my approach. But whatever it was, I listened. I engaged with every note Peter gave me. I admitted when I didn’t have an answer or hadn’t thought about one. And slowly the script took shape. Every scene built character and advanced story. Everything earned its place. It was in turns tightened and relaxed where needed. It became structured; allowing my more developed skills of dialogue and character development to have their place without becoming crutches. But here’s the crucial thing; for all the ways it changed from my original high school manuscript or the version I’d self-published in 2012, it was still absolutely the same story. It was just a much better version of it. And through it I realised that taking on board the lessons of VCA did not restrict me; it unleashed me. By using the tools they’d taught us, I could tell my stories and explore my ideas with renewed clarity, purpose, and self-reflection. I stopped accepting the most convenient solutions to complicated plot problems. I made myself think stuff through, to look for the most satisfying and compelling way to say and show what I had to. Even if I’d had any doubts about the ways in which I’d become a better writer thanks to not just what I’d learned through study but the experience of really interrogating a longstanding project, winning the Ustinov for that script quickly proved that the process had worked. I’ve experienced doubts and low points since, of course. But I never again had quite that same gnawing insecurity manifesting as ugly arrogance. The award showed me I was capable of good writing. I just had to put the work in to get there.

1 Comment

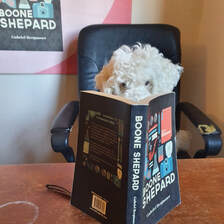

This is the third instalment in an ongoing series examining the lessons learned from early works. Read Part One here, Part Two here and Part Three here. *** There was a reason Boone Shepard became my first published novel and Windmills didn’t. It’s hard now not to view the publication of Boone Shepard as a culmination of sorts, the first time I really managed to put all of the lessons learned on earlier projects into practice. In the years following my first high school attempts, I’d always wanted to come back to Boone Shepard but never knew how. Whenever I’d toyed with making it darker or grittier or more realistic I lost interest fast. But as I started to reconsider those stories in 2013 I realised that the key was not doing any of those things. The key was tempering all the extremes so that the different moving parts could work in concert without undermining each other. Boone Shepard could absolutely be both silly and tragic, dark and optimistic all at the same time. But to avoid head-spinning tonal whiplash things had to be shifted. Characters redeveloped, slashed throats replaced with offscreen gunshots, giant tricycles with motorbikes; altogether bringing the series into the realm of an action-packed adventure story with a melancholic heart and a streak of absurdity. The moment I started planning, I knew I had something. It was personal but not to a fault. It was uniquely me in style and content. It offered something to audiences who didn’t care about any of the above. It sat squarely in a recognised genre, comparable to popular titles without imitating them. That doesn’t mean the Boone Shepard Trilogy was perfect. There is so much I would change about those books if I were to write them today. But then, I’m not convinced I could write them today. Sometimes you can revisit old works again and again, finding new notes to play and new ways to approach previously shaky ideas. But other times you have to accept that the piece was representative of the person you were at a different stage of your life, and that for better or worse it fulfilled the vision and intentions of that person. Boone Shepard was published by Bell Frog Books, a tiny publishing house started by a friend of mine who had read the original high school drafts and was convinced that there was something to them. She believed in Boone enough to invest considerable money and resources in getting his story out into the world, but both of us were new to this and I suspect we both wondered if we were going to look stupid on the other side of the release. When Boone Shepard was nominated for the Readings Young Adult Prize alongside books that have gone on to be modern classics, such as The Road to Winter and The Bone Sparrow, my imposter syndrome retreated just a little further. Not because that external validation meant that Boone or myself suddenly had worth we hadn’t previously, but because seeing my strange little high school fever dream sitting on shelves next to some serious heavy hitters, I started to think maybe there wasn’t some big secret to being a writer after all. Maybe it really was just time and effort and lessons learned. Or maybe I’d just managed to trick everyone. Either, really, was fine by me. But there was maybe one thing I was missing before I could realistically consider myself a good writer, and it was something I stumbled on completely by accident in 2014, a little while before the first Boone Shepard book was published. Nearing the end of my Masters of Screenwriting with no clue of my next step, I was at a weird kind of personal crossroads, lost and alone and unsure of my future or who I was. In that lonely period I took solace in old friends. Namely, I wrote a sequel to Windmills. It was something I’d thought about doing for years, despite the original’s peak success being a badly self-published version that sold maybe thirty copies. But I’d never really had a sequel idea that stuck until, suddenly I did. The story basically tumbled out of me fully formed; there was very little hair pulling or agonising, I knew where the characters were, what they were going through and what was going to happen. It remains to this day the easiest and most enjoyable writing experience I ever had because I just felt so in tune with the story, as though everything I was writing worked with startling ease. But what stood out the most was something I’d never considered myself to have a great handle on, which was the prose. Or maybe more specifically, the voice. I wrote it from three alternating perspectives; those of Leo and Lucy, the survivors of Windmills, and of Ben Hanks, a good but troubled cop looking into the events of the previous book. In the very first paragraph of the first chapter, written from Ben’s perspective, I started writing in a way I’d never done before. It wasn’t the grandiose, faux-sophisticated style of my early stuff, the more conversational approach I’d adopted post the autobiographical project or even the quirky-but-still-conversational style of Boone Shepard. No, Ben’s voice was totally different. Cynical but decent, hardened but not emotionless, haunted but not ruined. I’d never written a character like him before. I’d never thought I could. Most of my characters sounded like slight variants of myself. But writing as somebody so removed from me in both perspective and experience freed me up somehow. It let me experiment a little, let me for the first time try to write something with its own unique sort of beauty. I don’t want to go as far as to say I was aiming for poetic because I wasn’t, but I was beginning to understand that alterations in voice and style could create the tone I was looking for, one of melancholy, regret and fragile but maybe underserved hope. I think it was and remains one of the best things I’ve ever written. But none of that mattered. It was a direct sequel to a self-published novel that was required reading for this one to make any sense. I wasn’t keen to self-publish again, so the new book ultimately ended up as something I wrote for myself and the handful of people who were interested in the next chapter. I’m still proud of it and it’s still just sitting in a folder on my computer, unlikely to ever see the light of day. But what it did was lead me to fall back in love with a story that was, after no small amount of difficulty, about to change my life. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed