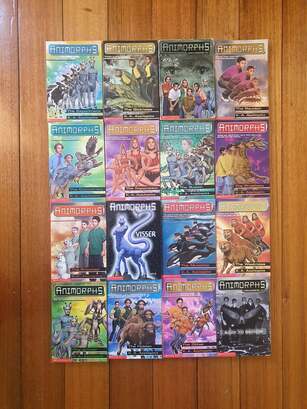

This is the third part of an ongoing Animorphs retrospective - check out Part One, Part Two and Part Four. Learning as a kid that most of the later Animorphs books had been ghostwritten, I felt betrayed. But this, of course, was before I understood that TV shows, among many other long-form stories, are written by multiple people with one showrunner overseeing the narrative. Animorphs’ development was only unique for its medium and even then, not so unique for the 90s heyday of Scholastic Book Clubs and series with upwards of fifty instalments released monthly. Coming into my re-read, I wasn’t bothered by the ghostwriting of it all. But now, three quarters through and well into the era of the ghostwriters, my feelings are mixed. With every new book that does absolutely nothing to advance the plot or characters (and in some cases actively impedes them), I get a little more frustrated. It doesn’t help that it’s in the many lightweight filler books where the ghost-writing is the most obvious – a lot of the darker, more plot heavy instalments are as good as if not better than any highlight from the early days of the series. For example; book 33, which absolutely kicked me in the heart. The Animorphs discover that the Yeerks are perfecting an anti-morphing ray that could force them to reveal their human identities. So they come up with a pretty clever plan – get Tobias, who is trapped in the body of a hawk but has since regained his morphing abilities, to morph Andalite (the alien race the Yeerks think the Animorphs are), demorph to bird in the presence of the Yeerks then let himself be captured. The Yeerks will use the ray on him, not realising that bird is his true form, and when he doesn’t change, they’ll assume their ray doesn’t work. At which point the Animorphs will mount a rescue mission and “accidently” destroy the ray. It initially works, but when the Yeerks realise the ray isn’t doing what it’s supposed to, they start straight up torturing Tobias. And that’s… the whole book. Tobias slips between his nightmare reality and hallucinations that are by turns confounding, gut-wrenching and beautiful. He’s rescued in the end, but over the following books it’s clear that he’s been profoundly damaged by the experience and nobody knows how to help him. Then in book 34 Cassie has to share her mind with the consciousness of Aldrea, the protagonist of probably the best Animorphs book, The Hork-Bajir Chronicles. HBC meant so much to me as a kid that I was really looking forward to this quasi sequel, which I never got up to back in the day. It didn’t disappoint, building beautifully on the themes and characters of the earlier book, advancing elements of its narrative without undermining the bleakness of its ending. Experiences like this are the best thing about revisiting this series as an adult – getting a kind of belated catharsis for stories that meant a lot to me growing up. But the rest of the books in this quarter are a lot more variable, quality-wise. Even the generally good ones are beset by plot holes and logic leaps, creating a sense that the narratives weren’t really thought through. Which is understandable given the publishing schedule, but considering how solid the plotting was to begin with, it’s disappointing. It was this issue that led to the first real case of me being let down by one of the books I loved as a kid. I always adored Megamorphs #3: Elfangor’s Secret, which sees the Animorphs trailing a time travelling Yeerk throughout history attempting to stop him from altering major battles in order to make the human race more susceptible to invasion. Throughout the book the Animorphs all get killed in various horrible ways only to reappear after the next time jump for reasons too complicated to explore here. I always remembered the harrowing image of the back of Jake’s head being blown off as he attempted to cross the Delaware, or of Rachel torn in half by a cannonball at the battle of Trafalgar. Reading it now, it’s this book more than any other that engages most directly with Applegate’s central theme of the cost of war. But it ends on the Animorphs making one of their patented horrifying moral concessions, only for it to not land because there are so many clear alternatives. It makes what should be powerful and haunting feel hollow. And it isn’t the only recent example of the Animorphs jumping to the most extreme, morally dubious solution despite the several obvious better ones. If you’re being charitable you could argue that the kids have become so desensitised that more palatable options don’t occur to them, but I don’t buy that. It feels like the series is trying to maintain its through line of moral ambiguity despite the rushed writing process meaning that said ambiguity isn’t thought out the way it once was. Which dulls the impact. A similar leap underpins book 30, which concerns Marco grappling with the choice to kill his mother, who is infested with one of the most powerful Yeerk generals. But there are so many other possibilities that the writer just seems to ignore and so when the moment comes for Marco to push his mother off a cliff (she survives, but still, rough) I just couldn’t quite get on board with it as the act of soul-destroying necessity it was clearly intended as. At this point in the story she’s a fugitive – why not kidnap her for three days and starve the Yeerk out of her head like they did to Jake way back in book six? A later book, Visser, does go some way to offering an explanation, but it’s an explanation tied directly to changed circumstances and as such not actually pertinent to the choices made in 30. Furthermore, instalments I might previously have found charming or entertaining started to grate. Take the book in which the Animorphs, well, discover Atlantis only to find it’s populated by mutated monsters who turn shipwrecked sailors into macabre museum displays. Taken in isolation it’s a fun, creepy read with some cool ideas. But this late in the game, every book that doesn’t contribute to the overall arc runs the risk of being annoying, no matter how well it might work on its own terms. And none of this is even mentioning paperback bound middle-fingers like the one where the Animorphs discover the Yeerks are trying to use cows to eradicate free will or the one where Jake goes away and Rachel suddenly becomes a power-hungry lunatic who regularly refers to herself as ‘the king’. Some characters, like Marco or Tobias, survive the various ghostwriters largely intact. Others, like Rachel or Ax, see their personalities wildly vary from book to book, scarcely in any way that’s flattering. Oh, and there’s a deeply haunting book where Cassie accidently gives the morphing power to a buffalo and I still think about it way more than I should. Sustaining the early energy and quality of any book series is hard. Sustaining it over sixty books, many of which were written by one-off authors on a monthly basis? It’s astounding that Animorphs at this point in its run remains capable of all timers even if they’re relatively rare. Ultimately I’m enjoying the re-read too much for the issues to overly matter, but they do reinforce my belief that the best way to read Animorphs in a modern context is to get ruthless with which books you read and which ones you skip. I’m committing to reading them all, but I couldn’t in good conscience recommend anyone without a similar nostalgic love for the series do the same. The good stuff is brilliant. The less good stuff becomes more exponentially punishing as the story nears its end, worsened by how obvious it can be when somebody who is neither Katherine Applegate nor Michael Grant wrote it. But none of that changes how I feel about the looming end of my re-read. Fifteen books left. Fifteen until I finally reach the final instalment. In the past few months I have read forty-seven of these and somehow, frustrations aside, I’m not ready to say goodbye. But given I started reading this series in 1999, it’s probably about time I found out how it ends.

0 Comments

My oldest friends still roll their eyes when I say the word Windmills. Which is fair enough, because at this point that word is synonymous with ‘pathological inability to let go’. Windmills was originally a novel I wrote in year twelve, which became a play which became a novel again which became a screenplay then a novel again and in between spawned all manner of sequels, spin offs and derivatives as I tried to find my way to a version that worked. The closest it came was the TV pilot adaptation that won the Ustinov in 2015, but even that ultimately never saw the light of day.

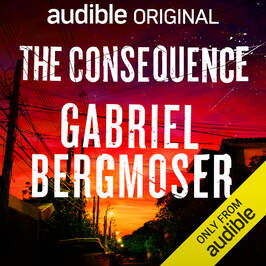

Time and time again I was told to let it go. Time and time again I refused. I was always sure that THIS version would be the one to get over the line. A belief quickly amended when the next version came along. The last time I tried to tell this story, my now-agent very kindly pointed out how for many reasons it just fundamentally didn’t work. Finally I listened. I moved on. I wrote The Hunted, The Inheritance and The True Colour of a Little White Lie. For three years I stayed away from Windmills. But a few months back, needing a new book for my YA contract and not having any ideas, I picked it up again. I didn’t advertise the fact. Too many times before I’d believed Windmills’ moment had come then been proven wrong. I fully expected the same thing to happen again. But I tried anyway. And with the benefit of distance, I approached it differently, treating it like a totally new book. Characters were overhauled, long clung-to plot points rethought. Crucially, I stopped thinking of it as Windmills but instead as something new emerging from the ashes of so many old drafts. When the draft was finished I wasn’t sure what to think. After so long it was impossible to look at the manuscript with any clarity. But knowing I had done all I could, I sent it to my publisher and I waited. I was nervous, ready for the rejection, for yet another version of Windmills to be sent to the bottom drawer. Today I got a phone call from her. I didn’t pick up straight away. It took me a moment of courage mustering. I had to try and keep the waver out of my voice when I finally answered and waited for her assessment. “It’s brilliant.” I was overwhelmed with relief. But it was only after I got off the phone that something else hit me. The surreal realisation that after twelve years of obsession, this story, or a version of it, is finally going to hit shelves everywhere. It won’t be called Windmills and it won’t look very much like other versions you might have seen over the years, but at its heart it will be the same story I started writing when I was seventeen. So many people have been a part of this journey. Too many to name. Everyone who read drafts and gave feedback, who performed in and directed the various stage versions. Every one of you who helped me see with a little more clarity what this story had to be. I owe you all so much. The journey isn’t over yet. There will be edits and rewrites and promo but by this time next year the story will be out in the world and after that, its fate is no longer in my hands. For the first time in over a decade, I think I’m okay with that. Anyway. I can now officially confirm that the novel formerly known as Windmills will be my next book.  Back in 2014, while working on a thriller manuscript, I ran into a problem. My main character, a good cop in a dangerous world, had ended up in an impossible corner and needed help. But a key part of the story was that he had been left without allies, which meant his rescuer had to be somebody new. Quickly I came up with a fun but functional character; a rogue ex-cop with underworld connections and a sharp, cutting wit, the kind of guy with a wolfish grin, a cigarette always stuck behind his ear and an ambiguous moral code. His name was Jack Carlin and, as intended, he turned up, played his part, and bowed out of the story after two brief scenes. That book never saw the light of day. And while I’d enjoyed writing Jack, I didn’t really think about him again. Until I was writing the first draft of what would become The Inheritance. Maggie was exploring her father’s history as a corrupt cop and to further that I needed somebody who was from that world but on her side. Somebody whose dangerous exterior masked a twisted sense of honour. Jack fit that bill and so he jumped over from the previous manuscript, except this time his role was bigger and so I got to know him better, learning more of why he was the way he was, what drove him. He was still a joy to write, and I figured he would reappear down the line as a recurring role in further Maggie stories. Then, while developing our lockdown web series The Pact last year, I was casting around for a surname for protagonist Morgan and caught sight of ‘Carlin’ on my bookshelf. Immediately I thought ‘damn, I’ve already used that’, then moments later thought ‘hang on, what if…’ So Morgan became Jack Carlin’s daughter and while The Pact was every bit her story, it gave me the opportunity to explore Jack from a different angle. It also meant that somebody had to play this character who had for so long existed only in my head. As far as I was concerned, there was only one somebody for the job. Greg Caine appeared in two episodes of The Pact and brought Jack to life perfectly. The little smirks, the quick responses, the glimmers of pain underpinning his seemingly harsh choices – he was every bit my character. Clearly, by this point Jack Carlin had a hold on me. Which meant that when my agent asked if I’d be interested in writing an original novella for Audible, it took about three seconds for me to realise who it would be about. And one more second for me to realise who had to read it. So, after seven years of supporting other character’s stories, Jack finally takes centre stage today in The Consequence, a crime thriller all his own. I wrote it alongside the final version of The Inheritance and while it’s linked to that book, it’s also very much its own thing; a bruising, wry, blast of pulpy Aussie noir. I’m really proud of this little story but more than that, I’m stoked that readers (listeners) now get to hear Jack Carlin’s own story in his own words, brought to life by Greg’s pitch perfect narration. The Consequence is available to listen to now, free with an Audible subscription/trial. I hope you like it. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed