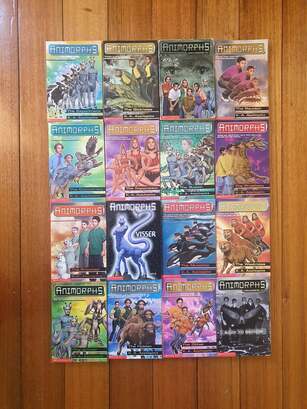

This is the third part of an ongoing Animorphs retrospective - check out Part One, Part Two and Part Four. Learning as a kid that most of the later Animorphs books had been ghostwritten, I felt betrayed. But this, of course, was before I understood that TV shows, among many other long-form stories, are written by multiple people with one showrunner overseeing the narrative. Animorphs’ development was only unique for its medium and even then, not so unique for the 90s heyday of Scholastic Book Clubs and series with upwards of fifty instalments released monthly. Coming into my re-read, I wasn’t bothered by the ghostwriting of it all. But now, three quarters through and well into the era of the ghostwriters, my feelings are mixed. With every new book that does absolutely nothing to advance the plot or characters (and in some cases actively impedes them), I get a little more frustrated. It doesn’t help that it’s in the many lightweight filler books where the ghost-writing is the most obvious – a lot of the darker, more plot heavy instalments are as good as if not better than any highlight from the early days of the series. For example; book 33, which absolutely kicked me in the heart. The Animorphs discover that the Yeerks are perfecting an anti-morphing ray that could force them to reveal their human identities. So they come up with a pretty clever plan – get Tobias, who is trapped in the body of a hawk but has since regained his morphing abilities, to morph Andalite (the alien race the Yeerks think the Animorphs are), demorph to bird in the presence of the Yeerks then let himself be captured. The Yeerks will use the ray on him, not realising that bird is his true form, and when he doesn’t change, they’ll assume their ray doesn’t work. At which point the Animorphs will mount a rescue mission and “accidently” destroy the ray. It initially works, but when the Yeerks realise the ray isn’t doing what it’s supposed to, they start straight up torturing Tobias. And that’s… the whole book. Tobias slips between his nightmare reality and hallucinations that are by turns confounding, gut-wrenching and beautiful. He’s rescued in the end, but over the following books it’s clear that he’s been profoundly damaged by the experience and nobody knows how to help him. Then in book 34 Cassie has to share her mind with the consciousness of Aldrea, the protagonist of probably the best Animorphs book, The Hork-Bajir Chronicles. HBC meant so much to me as a kid that I was really looking forward to this quasi sequel, which I never got up to back in the day. It didn’t disappoint, building beautifully on the themes and characters of the earlier book, advancing elements of its narrative without undermining the bleakness of its ending. Experiences like this are the best thing about revisiting this series as an adult – getting a kind of belated catharsis for stories that meant a lot to me growing up. But the rest of the books in this quarter are a lot more variable, quality-wise. Even the generally good ones are beset by plot holes and logic leaps, creating a sense that the narratives weren’t really thought through. Which is understandable given the publishing schedule, but considering how solid the plotting was to begin with, it’s disappointing. It was this issue that led to the first real case of me being let down by one of the books I loved as a kid. I always adored Megamorphs #3: Elfangor’s Secret, which sees the Animorphs trailing a time travelling Yeerk throughout history attempting to stop him from altering major battles in order to make the human race more susceptible to invasion. Throughout the book the Animorphs all get killed in various horrible ways only to reappear after the next time jump for reasons too complicated to explore here. I always remembered the harrowing image of the back of Jake’s head being blown off as he attempted to cross the Delaware, or of Rachel torn in half by a cannonball at the battle of Trafalgar. Reading it now, it’s this book more than any other that engages most directly with Applegate’s central theme of the cost of war. But it ends on the Animorphs making one of their patented horrifying moral concessions, only for it to not land because there are so many clear alternatives. It makes what should be powerful and haunting feel hollow. And it isn’t the only recent example of the Animorphs jumping to the most extreme, morally dubious solution despite the several obvious better ones. If you’re being charitable you could argue that the kids have become so desensitised that more palatable options don’t occur to them, but I don’t buy that. It feels like the series is trying to maintain its through line of moral ambiguity despite the rushed writing process meaning that said ambiguity isn’t thought out the way it once was. Which dulls the impact. A similar leap underpins book 30, which concerns Marco grappling with the choice to kill his mother, who is infested with one of the most powerful Yeerk generals. But there are so many other possibilities that the writer just seems to ignore and so when the moment comes for Marco to push his mother off a cliff (she survives, but still, rough) I just couldn’t quite get on board with it as the act of soul-destroying necessity it was clearly intended as. At this point in the story she’s a fugitive – why not kidnap her for three days and starve the Yeerk out of her head like they did to Jake way back in book six? A later book, Visser, does go some way to offering an explanation, but it’s an explanation tied directly to changed circumstances and as such not actually pertinent to the choices made in 30. Furthermore, instalments I might previously have found charming or entertaining started to grate. Take the book in which the Animorphs, well, discover Atlantis only to find it’s populated by mutated monsters who turn shipwrecked sailors into macabre museum displays. Taken in isolation it’s a fun, creepy read with some cool ideas. But this late in the game, every book that doesn’t contribute to the overall arc runs the risk of being annoying, no matter how well it might work on its own terms. And none of this is even mentioning paperback bound middle-fingers like the one where the Animorphs discover the Yeerks are trying to use cows to eradicate free will or the one where Jake goes away and Rachel suddenly becomes a power-hungry lunatic who regularly refers to herself as ‘the king’. Some characters, like Marco or Tobias, survive the various ghostwriters largely intact. Others, like Rachel or Ax, see their personalities wildly vary from book to book, scarcely in any way that’s flattering. Oh, and there’s a deeply haunting book where Cassie accidently gives the morphing power to a buffalo and I still think about it way more than I should. Sustaining the early energy and quality of any book series is hard. Sustaining it over sixty books, many of which were written by one-off authors on a monthly basis? It’s astounding that Animorphs at this point in its run remains capable of all timers even if they’re relatively rare. Ultimately I’m enjoying the re-read too much for the issues to overly matter, but they do reinforce my belief that the best way to read Animorphs in a modern context is to get ruthless with which books you read and which ones you skip. I’m committing to reading them all, but I couldn’t in good conscience recommend anyone without a similar nostalgic love for the series do the same. The good stuff is brilliant. The less good stuff becomes more exponentially punishing as the story nears its end, worsened by how obvious it can be when somebody who is neither Katherine Applegate nor Michael Grant wrote it. But none of that changes how I feel about the looming end of my re-read. Fifteen books left. Fifteen until I finally reach the final instalment. In the past few months I have read forty-seven of these and somehow, frustrations aside, I’m not ready to say goodbye. But given I started reading this series in 1999, it’s probably about time I found out how it ends.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

BLOG

Writing words about writing words. Archives

May 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed